Who Did It First? Style, Grades and Dispute in First Ascents

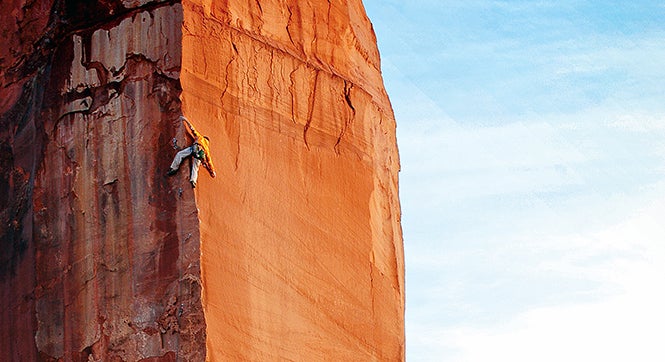

Tom Adams styles Excommunication (5.13b), one of a new generation of crackless tower routes, on the Priest, Castle Valley, Utah. Photo: Duane Raleigh.

Climbing grades don’t matter. You, me, us—we should just climb because it feels right or we’re trying to impress a girl…or a guy. Whatever comes first. Don’t judge. An unnatural focus on grades or definitions is to miss the whole point of climbing—freedom, travel, experience, intensity, overcoming boundaries. We all hate the grade police. Just get up the thing, right?

Not really. That’s half of the story. We, the pluralis majestatis, were in the Olympics, and companies far and wide took notice, with marketing budgets and opportunities for sponsorship following suit. With gobs of money pouring into our sport (Coke is sponsoring athletes now) comes the necessity for athletes to promote those products. In order for those athletes to get attention, they climb new and exciting things, FAs, FFAs, routes in exotic locations, light and fast ascents, naked ascents, and so on. Getting millions of eyeballs to read about climber X traveling around the world to send 5.7s is impossible; of course, that’s rad—no, really, climbing 5.7 is awesome—but it doesn’t make headlines. All good and fine thus far, and we shouldn’t judge.

And yet news abounds daily about claims of a certain type of ascent. A typical email—”Me and my team just climbed “x” in “x” style,” and so a claim is made. More often than you would think, the claim is inaccurate.

Climbs are tricks in a way, and since tricks can be performed with style, it’s only natural that climbing achievements are judged on improvements in style. In this context, style is not referring to how someone moves, but the way in which they chose to climb something. It’s a “game climbers play,” to cite Lito Tejada-Flores, and someone is always upping the ante. Alex Honnold’s free solo of Freerider on El Cap was one such improvement in style. Climbing doesn’t have objective measurements like line tape or a stop watch. We do have a rating system, but all climbers know body type is a huge factor. “Take!! I’m just too short for this move. It’s like 5.14 for me,” said everyone at some point.

Here’s a for instance: say you go out and climb the South Face of the Petit Grepon, in Estes Park, an eight pitch 5.8 on beautiful alpine granite, totally classic, and often crowded. A friend and I climbed the South Face a few years ago and we swapped pitches, as is normal on a typical trad outing. Yea, I’ve done that route, even though I didn’t lead every pitch. It was well below my ability on a gear route, so I didn’t feel the necessity of telling everyone, in conversation or whatever, that I had led half the pitches. No bounds nor speed record nor any record of any sort was broken that day, and it was perhaps all the better for that reason.

However, on ascents where performance levels are raised, collectively or individually, and they are reported upon, the stakes become higher, and it does matter. Climbing a 20-pitch 5.13 gear route and leading every pitch is exponentially harder than doing it with a partner and swapping leads.

In particular, magazines see a lot of incorrect reporting on the nuances between team ascents, free ascents, and individual ascents, among others. It likely comes from an over-eagerness to do something “first,” with a little bit of market pressure thrown in for good measure. Regardless, here’s some provisional thoughts, nothing in stone, and largely applicable to big wall rock climbing where the stakes are high. Let’s start with the simple stuff, then get more complex.

Individual ascents should be claimed when the climber leads all pitches, without falling.

Team ascents send the rig, but “swap leads.” This is the most common form of hard free ascents and first free ascents. In 2015, Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson sent the Dawn Wall as a team ascent and free ascent, since they swapped pitches; however, each sent the crux pitches. In 2016, Adam Ondra climbed every pitch himself, which amounts to the first individual ascent and second free ascent. Could Tommy and Kevin have each made the first and second individual ascents?—yes, of course. They just didn’t. Jorgensen wrote of Ondra’s ascent: “For Tommy and I, the question was whether it was even possible. We left lots of room to improve the style and Adam did just that!” Ondra’s ascent was an improvement in style, and arguably, in difficulty; however, having the vision and dedication to see the route, clean it and work it over years is more difficult in my estimation.

What about first female ascents (FFAs) in a mixed team? Can an FFA be claimed in a team ascent?

Single push ascents, as opposed to multi-day, refer to a climb being done in a single push, either by team or an individual, regardless if they have rehearsed it before. For instance, if you start climbing and then top out, without hitting the dirt to party on a rest day, then it’s a single push ascent. Lynn Hill was aware of this, and so, after her 1993, four-day team ascent of the Nose, she returned the next year to plant her flag with a single push (23 hours), leading every pitch herself—the first individual free ascent of the Nose. She wanted to do it in a better style. Ante up gents—“It goes, boys,” said Hill.

If you didn’t rehearse the route, then it’s a ground-up single push ascent. Assuming you didn’t onsight every pitch, did you pull gear on rappel?…since to properly claim a single-pitch trad send you can’t have pre-placed gear. The same should apply for big walls, right? It gets complicated. Did you stash food and gear up high? Did you have big-wall porters? Does that change anything?

Ok, down the rabbit hole some more. Say you have a 10-pitch project, and, over the course of the last five years, you’ve led every pitch. Maybe the first year you led pitches, 1-3, 7 and 9, and then on year five you led 4, 5, 6, 8 and 10. Can you claim the first free individual ascent?

Back to the Nose on El Cap for context…in 1998 Scott Burke nearly freed the Nose, an attempt that took 12 days, and he top-roped the Great Roof pitch because of impending storms. Tommy and Beth made a team ascent in 2005, and then Tommy made an individual free ascent in the same year, leading every pitch himself, in a single push, in 12 hours. Technically, in 2005, that means the only people to have sent the Nose individually were Lynn and Tommy.

I could easily keep going with distinctions—such as variation pitches—or take up the idea that naked, chalkless free soloing is the logical culmination of Royal Robbin’s “clean climbing” revolution, but I won’t. People ask how Honnold can be outdone—well there it is. Chalk and rubber are still quasi-technologies.

Style matters, and style informs difficulty, and we need to be clear about who did what and how. Since style is progressive, honesty is paramount.

For the majority of climbers, these distinctions don’t matter, but for those of us reporting on them, it does. As climbs are touted with increasing pressure from all parties to do something unique and singular, gone are the Warren Harding days of getting up the thing…unfortunately.