Photo Gallery: 30 Years of Redpoint Photography

"None"

Get to the Point

2016: Ethan Pringle, Blackbeard’s Tears (5.14c), Promontory, California

I gather as much info as I can every time I go up a route, and I’ll often keep refining beta until the very end—because it’s all about that micro-beta! On Blackbeard’s Tears, doing things efficiently is even more important since you’re placing gear. It’s all about putting in the work and not giving up—I spent 10 days on this climb. In the end, all I needed was a boost of confidence from a cool breeze that kicked in after days of smarmy conditions.

1987: Christian Griffith, Verve (5.13c), Boulder Canyon, Colorado

There is something existential about projecting—attempting what at first feels impossible but having the confidence that determination will prevail. Verve is a perfect line, a clean prow jutting into the narrows of Boulder Canyon. After much effort and split tips, I linked it. It was my most difficult send, blessed by a cool draft blowing down from the mountains and named for the magical wind of the ancients.

1987: Harrison Dekker, Dreams of White Porsches (5.13b), Mickey’s Beach, California

In 1980, I belayed Tony Yaniro on Colorado’s Sphinx Crack (5.13). I was impressed with his systematic approach: working moves and committing long, complicated sequences to memory. Years later, Dreams was fun to puzzle out with Scott Frye—like unlocking a boulder problem.

1991: Scott Frye, Surf Safari (5.13d), Endless Bummer Boulder, California

I spent my teenage years (1970s) at Indian Rock in Berkeley, working problems after school. Back then, roped climbing meant no dogging, so climbing and bouldering felt different. Once we got over the whole no-dogging thing, projecting opened our eyes to all sorts of routes, like this prow up the coast from San Francisco. Indian Rock gave us an expanded picture of what was possible.

1997: Chris Sharma, Biographie (5.15a), Céüse, France

I used to feel like the best attitude was “When it’s time to do it, I’ll do it, and if I don’t, it was’t meant to be.” Now, I feel like you have to keep banging your head against the wall and find a way to bring the redpoint energy to life. It’s more fun to just climb easier stuff you can do quickly, but there is a deeper journey available if you accept the challenge to go beyond your limits. A hard project exposes your weaknesses—it challenges you to improve as an athlete, but also as a human. You often find that you were capable of a lot more than you thought.

1996: Tommy Caldwell / Chris Sharma, Super Tweak (5.14b), Logan Canyon, Utah

From The Push: Given Chris’s minimal outdoor experience, attempting Super Tweak was like throwing Chris into the deep end to see if he could swim. Near the end of the [first] day, Chris sent it.

1996: Hans Florine, Mickey’s Beach Arête (5.13c), Mickey’s Beach, California

After one attempt on Mickey’s Beach Arête during which I couldn’t pull off the crux dyno, I remember thinking I’d never be a redpoint climber. Finally, I unlocked the crux and sent, surprising myself on a climb I’d just been messing around on to pass the time.

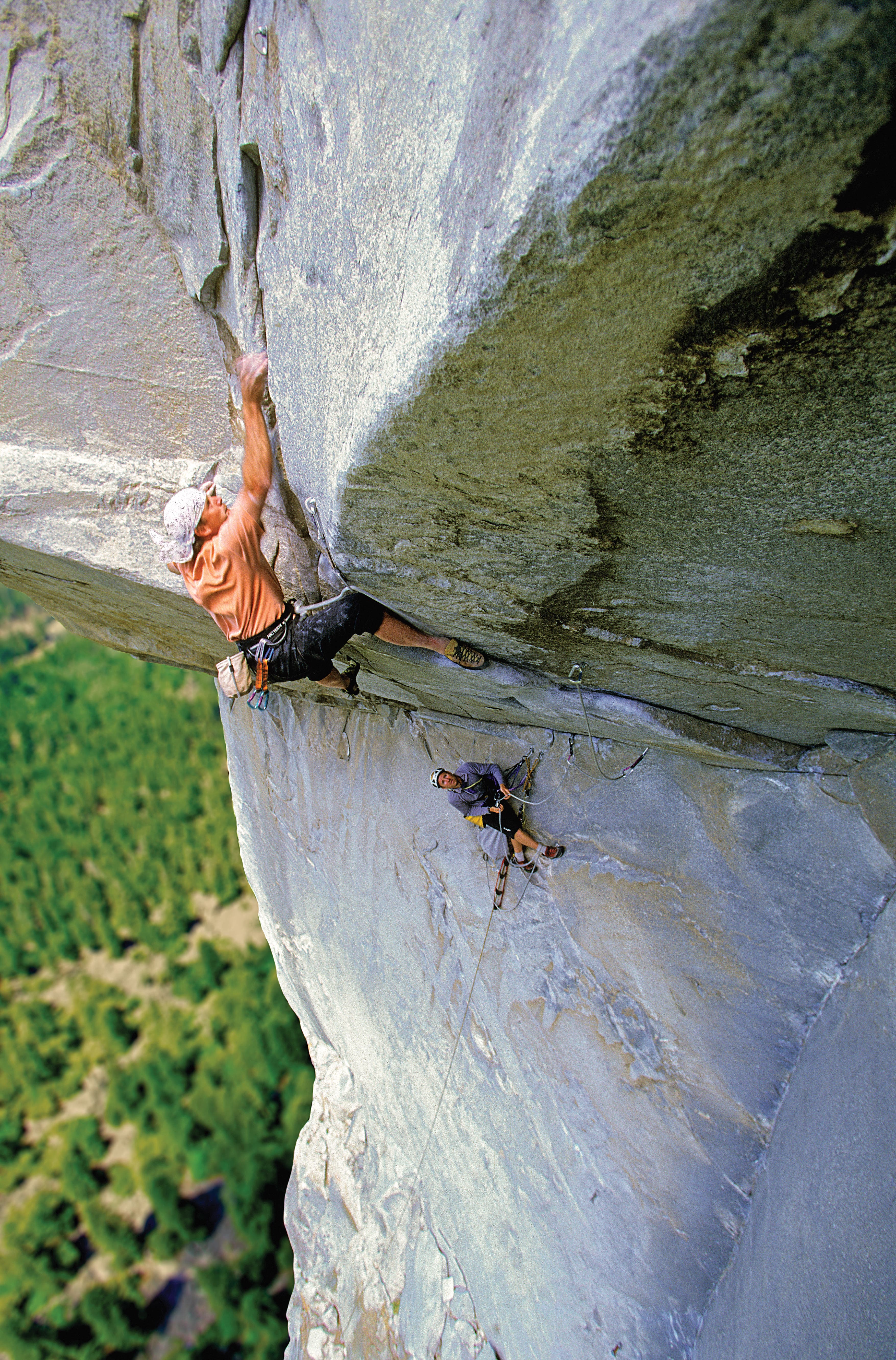

1996: Ron Kauk, Magic Line, (5.14b), Yosemite National Park, California

Yosemite is the most beautiful place on Earth—watching the maples grow leaves and then lose them, or the waterfalls change from raging to frozen. I tried and tried to cross over the wall between myself and this climb. Learning to accept the process was the key. Every day there, I learned to let go, to free my mind, and simply allow my heart to find the love for each move, which led to the core of my own truth: I love to climb!

2002: Sheri Kashman, Orange Juice (5.12c), Red River Gorge, Kentucky

Projecting gives me the opportunity to spend time on routes I’m stoked on. Orange Juice is perfect this way: It’s aesthetic, has amazing moves, and was a challenge. I like something feeling next to impossible the first couple tries and then having it slowly come together. Why wouldn’t I want to keep getting on a route I love?

2004: Todd Skinner, Wet Lycra Nightmare (V 5.13d A0), Leaning Tower, Yosemite, California

From Jim Hewitt, Skinner’s partner on the climb: “Todd worked out a wild sequence at the crux that involved pulling over the roof with a right heel hook and his right hand pinching the ‘hideous taco.’ The sheer forces wrecked his back, so he would start each redpoint day by crushing a dozen ibuprofen and sprinkling them on his Wheaties. The next season, when we sent, his back was better but his shoulder needed an operation. He was postponing it because he knew there would be a convalescence.”

2007: Lonnie Kauk, Peace (5.13d), Medlicott Dome, Tuolumne Meadows, California

When I was a kid, I remember seeing the poster of dad on Peace. I thought, “One day I’ll send it, too.” Peace is all about standing on your feet and staying calm the whole way. My philosophy is enjoy your process and never give up—when the time is right, you will send.

2015: Joe Kinder, Blue Skies, Dark Clouds (5.14c), Cascade Cliff, California

Projecting is a style in itself—it needs to be acknowledged as its own discipline. It requires patience, follow-through, belief, and lots of failure. Projecting is the ultimate form of intimacy with a pathway up a wall.

2008: Pamela Shanti Pack, Gabriel (5.13c), Zion National Park, Utah

When I was trying Gabriel, I was new to offwidth climbing, FAs, and projecting in general. I came to love the process during the two seasons on Gabriel. I had to learn and even devise inverted squeeze techniques. I cried when I sent, looking up at it for the last time as I lowered off. I have been obsessed with projecting ever since.

2013: JB Tribout on Crosta Panic (5.12a), Siurana, Spain

The process of bolting a line, finding the beta, and then thinking about a free ascent is very special—by far my best experiences in climbing, even better than winning a World Cup. The internal process between failure and success is so narrow. You have to push your body and mind with no guarantee of success.

2014: Carolyn Wegner on Sex (5.12a), Owens River Gorge, California

Projecting can teach you so much about perseverance and determination—and you can apply those lessons to other, more important life goals. At first it might feel overwhelming and impossible, but if you work hard and have patience, eventually you can prevail.

2015: Steven Roth on Raging Waters (5.14), Medlicott Dome, Tuolumne Meadows, California

My approach involves two steps: First, I spend enough time on the crux (or redpoint crux) to dumb down the moves, committing the body positions to muscle memory. Step two is rehearsal of all moves leading up to the crux(es). On Raging Waters, because there are hundreds of knobs (all bad), finding the easiest sequence was a challenge. A section that seemed like V10 would settle in at V6 with slight changes to foot and hip placements.

2015: Kevin Jorgeson on Ambrosia (V11 X), Buttermilks, California

Redpointing is all about mastery. With dangerous boulders or grit-style routes, it’s all about risk mitigation. Once I can do the moves with a rope, the real challenge is building enough confidence to do them without a rope. The result is an intimate familiarity with every single move, hold, and sequence. I love executing the choreography flawlessly. It feels like bending the laws of physics.

2015: Gabrielle Nobrega on Daphni (5.12b), Kalymnos, Greece

Redpointing used to intimidate me. I would put so much pressure on myself to improve on every go. I’m a lot more successful when I simply focus on climbing well—on the process—rather than the send.

2018: Kim Pfabe, Courtney (5.12a), Mickey’s Beach, California

I started climbing at 41, and after a year sent my first 5.10c. The decision to project Courtney was a motivational goal to climb 5.12a in my first 1.5 years of climbing. It took me just under six months to toprope, leaving a week to try to lead. On my third try, I fell at the last move, narrowly missing my deadline. Still, I learned so much, including techniques like backstepping, flagging, and dynoing. I won with a whole new set of “tricks” in my bag!

Click any photo for the full-size version.

As my friend “Doug” is fond of saying, “Redpointing is everything I hate about climbing. I don’t want to mess around with remembering moves and making them pretty. I just want to get in there and fight—I’ll get knocked down and bite ankles if I have to!” I get what he means: Grit and determination are undeniable assets in climbing, and Doug has those in spades.

It’s possible that Doug’s fierce distaste for redpointing is related to the roots of our sport, in which the original goal was to walk up to a mountain and climb it by “fair means”—solving its challenges on the go. In my own early California climbing days (1980s), I learned that “rehearsal” and “pre-inspection” were two of the most egregious crimes an American climber could be accused of. If you fell, you were supposed to lower off, pack up your crap, and return when you were better. Even the forgotten practice of “yo-yo-ing” didn’t allow for rehearsal. The only exception was if you were on a multi-pitch route and in survival mode—but only if you later confessed to your poor style, aka doing the route “French Free.”

Ironically, the less dogmatic Euros simply considered such tactics normal. In 1973, the late German climber Kurt Albert invented the concept of redpoint climbing—he would paint a small red dot at the base of aid climbs he’d freed in the Frankenjura. And yet like Doug, even Albert had a distaste for working on a route for more than a few days.

Like a work of art, a climb can be realized in a brilliant flash of inspiration or it can be the result of weeks, months, or even years of refinement. In 2013, Alex Megos became the first climber to onsight 5.14d when he walked up to Estado Critico in Siurana, Spain, and fired it in a virtuoso performance. Conversely, Tommy Caldwell famously spent seven years dreaming, scouting, and working on the Dawn Wall (VI 5.14d) of El Capitan before his and Kevin Jorgeson’s FFA in 2015.

Both approaches have their place, but for me, the greatest art is found within the latter. The craft of redpointing can border on mystical, especially with a first ascent, a tabula rasa that no one has climbed before. Over the years, I’ve spent a lot of time coaching fellow climbers to redpoint. I fell in love with projecting in the 1980s while trying hard boulder problems at Indian Rock in Berkeley, California, and later while attempting first ascents with friends at nearby Mickey’s Beach. Those climbs were beyond my ability to flash or do second try; instead, I worked on them until they began to make sense. In the process, I learned to be patient and to believe. Meanwhile, my passion for photography was a direct offshoot of my passion for climbing; I wanted to share the excitement I felt as our dreams turned into these visually stunning new climbs.

As a photographer, I’ve had a front-row seat to some amazing ascents during the 30 years I’ve been shooting. Memories include witnessing the ups and downs of Ron Kauk’s multi-year bid on Magic Line (FA: 1996), a 5.14 thin crack next to Yosemite’s Vernal Falls that went unrepeated until Kauk’s son, Lonnie, did it in 2017. And watching Chris Sharma, just 17 at the time, decipher the crux moves on Biographie (5.15a) in 1997. A few weeks later, Chris, beat down by the unrelenting difficulty of the monster line, received a pep talk from Lynn Hill, who encouraged him to focus on the more manageable process of refining his beta and efficiency rather than on the daunting feat of sending the entire climb. More recently, in 2016, I witnessed as Ethan Pringle walked a fine line between motivation and burnout on the first free ascent of the spectacular trad line Blackbeard’s Tears (5.14c) on the Northern California coast, one of North America’s most difficult traditional pitches.

While documenting these experiences was enlightening, it wasn’t so because of the climbs’ extreme difficulty; instead, it was for the privilege to witness how much effort, passion, and emotion went into each ascent. Ultimately, these are experiences that can be had by any climber at any level who is willing to commit to a climb and stick with it, send or fail. The mental, physical, and tactical barriers we break are the same at any grade.

On these pages, you’ll find a semi-chronological record of redpoint attempts and ascents from my three decades’ of shooting. Some images document epic battles that took years, while others are rough-hewn second-try sends. I prefer to shoot the longer battles. They give me multiple attempts to refine my vantage points, capture different light, learn from my mistakes, and ultimately “work” my way to a photographic redpoint—a tactic I much prefer to getting in there and, as Doug phrases it, biting ankles.

Online Course: The Art of Redpointing

Ready to redpoint your hardest— and smartest—ever? Learn how in our new AIM Adventure U class The Art of Redpointing. Co-taught by pro climber Heather Weidner and the climbing and mental-training pioneer Arno Ilgner, author of The Rock Warrior’s Way, this comprehensive 9-week course deconstructs the essentials of projecting, including mental, logistical, and training tactics. On sale now; visit The Art of Redpointing for more.