A Great North Carolina Classic That's Roadtrip Worthy

Erica Lineberry on the smooth slabs of Great White Way (5.9), Stone Mountain, North Carolina. (Photo: Bryan Miller)

Stone Mountain, iconic cliff and namesake for Stone Mountain State Park in North Carolina, is a broad granite monolith nestled in the Blue Ridge Escarpment, an abrupt elevation transition between the state’s flat Piedmont region and the lush Blue Ridge Mountains extending west. As a single 600-foot-tall “boulder,” the igneous dome has very few protectable features and even fewer holds. It is the realm of the friction climber, a purist’s dream of uncompromising ethics and singular style. Route development, starting in the early 1960s, was mostly ground-up, which on a nose-over-toes friction dome forced climbers to be bold. In 1971, Bob Mitchell and Will Fulton, early pioneers of the area, developed Grand Funk Railroad (5.9-), a five-pitch classic smearfest that set the tone.

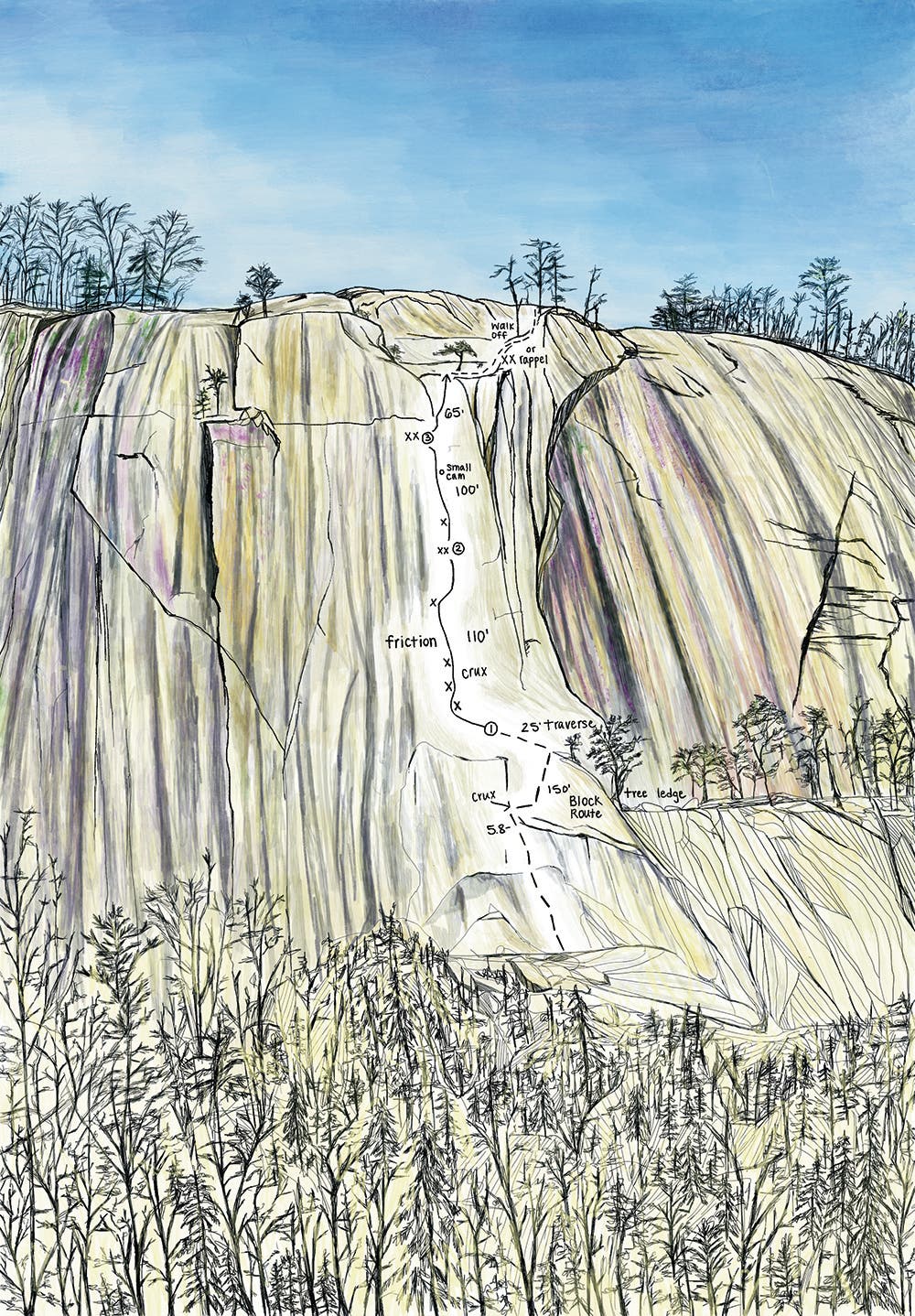

While the crag has approximately 50 quality multi-pitch routes from 5.4 to 5.12—for the most part on its sunny south face—there is no finer example of unadulterated Stone Mountain friction than the Great White Way. This three-pitch 5.9 was established by Gerald Laws and Buddy Price in February 1974 and tackles a smooth, continuous water groove—picture a luge chute made of polished milky-white quartz. With only five protection bolts total—four on the crux first pitch, and a lone bolt on the sustained 5.8 second pitch—it can rattle even the most experienced climber.

Laws, who along with George DeWolfe, Will Fulton, Tom McMillan, Jim McEver, Bob Rotert, and others, was a driving force at Stone Mountain, recalls that the route had been attempted a few times before his efforts, evidenced by a lone quarter-inch bolt at the start of pitch one. When he and Price, an affable climbing fixture in the Carolinas, established the line during a two-day push, they were happy to use the in-situ hardware. “I clipped the bolt and finally managed to negotiate the steep opening 20 feet by manteling a small crystal with my thumb,” Laws recalls of the technical crux. Laws wore EBs, a climbing shoe introduced by French master bootmaker Edmond Bourdonneau in the 1950s. And while the EBs were a quantum leap forward in performance from lugged mountain boots, they were clad with slick, hard rubber.

We finished the day atop the dome with the setting sun painting the distant mountain ridges orange while an inky blue shadow crept up the cliff below us. Before rappelling, Lineberry and I both looked down the groove with the same thought: If you were to link all three pitches in a continuous 300-foot run, you could protect the entire climb with exactly seven quickdraws and a partially cammed number-two yellow Metolius in a shallow vertical pocket just below the pitch-two anchors. And try as we did that day, we could label the route neither “traditional” nor “sport.” Instead, it was a white-knuckled affair defined by knee-knocking runouts and a pressing need to discern the smallest details in the blank rock—a small change in texture here, a minute undulation there—that we could use to make upward progressMore than 45 years later, I made the same move using the same thumb-mantel crystal. Even with sticky rubber, I felt I could have slipped there—or at any point along the next 300 feet. As I photographed Erica Lineberry, an accomplished Trango climbing athlete, tiptoeing in and around the continuous water groove 75 feet above that lone pitch-two bolt, she mused, “I wonder if I could hit the ground from here?”

When I asked Laws about the long runouts, especially the infamous one on sustained 5.8 friction on pitch two, in his warm Southern drawl he replied, “I couldn’t stop to hand-drill because there was nothing to stand on. I had to keep moving or I would have greased off in those uncomfortable EBs.”

Laws, now 78 years old and retired, started climbing in 1969, and soon thereafter began making his own bolting hardware from stainless-steel angle iron as well as rappel devices from aluminum blanks. He is a white guy who grew up in the Southeast, a region with a poor track record when it comes to human rights. As such, it was probably no surprise that the route name, Great White Way, has been repeatedly flagged on Mountain Project, a fact that torments Laws. “We had been climbing up on Stone 13 or 14 straight weekends that winter,” remembers Laws. “We just loved it up there.” Laws recalls how the groove would transform into a stunning white rivulet during rainstorms, this spectacle—and not any sort of racial doctrine—inspiring the route’s name. As we talked about Laws’s heyday on Stone, several things were palpable: his deep affection for the place and for the climbing community, and an intimate fondness for runout friction climbing.