Six Classic Free Routes With Cruxes You Can Skip (Just in Case)

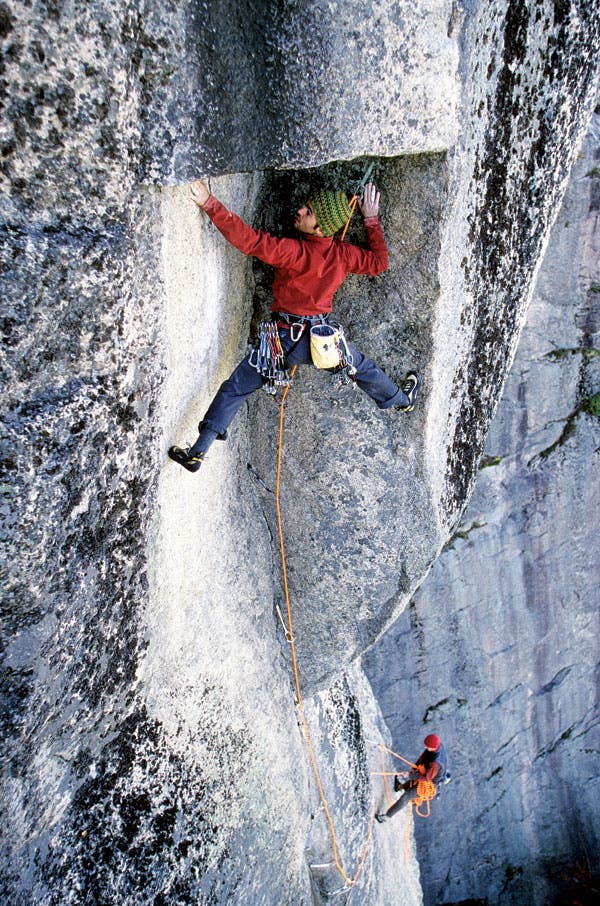

Splitter rock and solid cam placements make many classic free climbs a more-approachable endeavor. (Photo: Alex Eggermont / Aurora Photos / Getty Images)

I wanted to do Monkeyfinger, but I didn’t climb 5.12. My partner did, though, and she wasn’t going to let me hold her back with any sanctified notions of “saving” the route for a pure free ascent. Monkeyfinger, a classic nine-pitch corner in the back of Zion National Park’s main canyon, has just one 5.12 pitch; the rest is mostly 5.10, with two short 5.11 cruxes. “You can pull on a piece through the hardest part,” she said. “Let’s just go for it.”

And so we did. She fell once on the crux Black Corner and then smoothly redpointed the pitch. On toprope, I groped at the fingertip laybacks, sagged onto the rope, and then yarded on a nut and pulled into a good rest. The other pitches were a blast—and I climbed them all free.

Some climbers wait to attempt America’s greatest free routes until they’re good enough to do them in perfect style. But what if you are never that good? Purists would say you should stay off the climb—leave it for those who have the necessary strength and talent. I say go for it: Do your best to free climb, but don’t hang your head in shame if you pull on a piece or stand on a bolt. Very few climbers consistently cruise long 5.11 to 5.13 routes.

Of course, you should not tell anyone you “did” Astroman when you aided through the crux boulder problem near the bottom and hung at the mouth of the Harding Slot. But take it from me: Climbing Astroman in such “A0” style is still a challenging, highly rewarding day. And as long as you’re completely honest about your efforts, why should anyone else care? You can always go back for the redpoint.

D7 (5.11d/5.10, 7 pitches)

Longs Peak, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

Following a continuous line of cracks straight up the left side of Longs Peak’s famous Diamond, D7 became the most popular route up the face soon after its first ascent in 1966, and when John Bachar and Richard Harrrison freed the line in 1977, it quickly became the route of choice for talented climbers looking to step up from the Diamond’s “easy” free climbs. The five- to seven-pitch route’s popularity has left a legacy of fixed pitons and other pro that make it nearly a clip-up for free climbers—many carry only a single set of cams and nuts and a harness racked full of quickdraws.

Low on the route, the climbing is mostly steep, juggy 5.9—a surprise on such an intimidating face. This moderate terrain ends with a spot of 5.10 just below a wide crack, and then another 5.10 pitch. You can aid all of this section (at least one four-inch piece needed for the wide), but it will go much quicker if you’re able to free most of it. Above lie the cruxes: a 15-foot bulge slashed with parallel finger cracks, another short 5.11 passage, and then a thin crack that starts hard (5.11a) but soon widens and eases. You can do these cruxes with A0 tactics, but if you’re heading up the route expecting to aid, a single pair of alpine aiders will make the task much easier.

The Casual Route (5.10a), the easiest line up the Diamond, also gets easier with a wee bit of aid. A couple of tugs on gear (there’s usually a fixed pin) at the crux bulge on the seventh pitch bring the route’s grade down to about 5.9— though 5.9 still feels plenty hard at over 13,500 feet.

The Prow (5.11+/5.10a, 6 pitches)

Cathedral Ledge, New Hampshire

After many attempts by many different New Hampshire climbers, Jim Dunn snagged the first complete free ascent of The Prow in 1977, and a quarter-century later it remains one of New England’s great free climbing prizes. The Prow is also a traditional favorite for clean aid practice—a sort of mini–big wall warm-up for Yankees heading to Yosemite Valley. The route takes a plumb line up Cathedral’s steepest buttress for six mostly short pitches, and the numerous fixed pitons and smattering of bolts make it an appealing target for climbers of all stripes: free, aid, and those who mix it up a bit.

The Prow is a perfect route for “might as well give it a try” free climbing: You can safely go for it, but if you come up short, it’s no bother to aid through and try again on the next pitch. As local guide Mark Synnott says, “The hard moves are definitely cruxy, but they’re short, and you almost always get back to a good stance within a few moves.” Half of The Prow’s pitches are upper end 5.11, but the second- and fourth-pitch cruxes are essentially boulder problems that quickly succumb to A0 tactics; the fourth pitch continues with a sweet 5.11a finger crack that can be freed or aided.

The route’s crux fifth pitch heads up a corner and through a small roof; the difficulties are sustained, but the pitch is quite short, and there’s usually lots of fixed pro. Another superb finger crack (5.10a) gains the top and superb views of the Mt. Washington Valley. From here, it’s usually easy to convince a highly impressed tourist to drive you back down the paved summit road.

Monkeyfinger (5.12b/5.10+, 9 pitches)

Zion National Park, Utah

Discovered by the great Zion pioneer Ron Olevsky, and then free-climbed in 1984 by Pokey Amory and Drew Bedford, Monkeyfinger has all the elements of a classic: a compelling line, three-minute approach, and solid sandstone. It also has some nice surprises: The poorly protected start of the second pitch (5.10+/5.11-) can be avoided with a step left into a better crack, and the intimidating offwidth on pitch six has jugs hidden in the back of the crack. The crux Black Corner (5.12b, pitch three) is short and easily aided by pulling on a couple of nuts or tiny cams. If you do it this way, the free-climbing crux will come on the following pitch, with a hard move around a roof. This, too, will succumb to a tug on a piece, but with good pro at your waist, give free climbing a try!

If you cruised the crux corner, another challenge awaits on a sixth-pitch variation called the Monkeyfinger Crack, a 5.12 finger-jamming exercise on the exposed wall left of the Monkey House alcove. Most people avoid this alternative by continuing up a short 5.10+ layback and jam crack, followed by two funky pitches of face climbing and general desert weirdness. The rock quality deteriorates on these final pitches, and some people start rappelling at the Monkey House, before finishing the route. But if you really want the full Zion experience, be sure to top out on the canyon rim before rapping.

Levitation 29 ( 5.11c / 5.10, 10 pitches)

Red Rock National Conservation Area, Nevada

You can bet Lynn Hill and John Long didn’t yank on any of the plentiful bolts on this route when they free climbed it in 1981, shortly after the first ascent by George and Joanne Urioste and Bill Bradley. But if the brief 5.11 cruxes on the second and fifth pitches spit you off, don’t hesitate to grab a silver handhold and keep going—the rest of the climbing is totally worth it.

The setting for Levitation 29 is amazing: a two to three-hour approach brings you to a shelf high over Oak Creek Canyon, at the foot of the Eagle Wall’s rippled sandstone. Although the route has dozens of bolts, it’s not a sport climb; you need a small rack and good trad skills, especially for the first two pitches. The crux crack on the fifth pitch requires strenuous fist jams for free-climbing success, but the bolts alongside offer an easy out. Many rappel after the sixth pitch, when the sandstone begins to soften, but good climbing lies above, and the walk down is gorgeous.

Grand Wall (5.13b / 5.10+, 9 pitches)

Stawamus Chief, British Columbia

With 12 pitches of superb granite crack and face climbing up the center of Squamish’s premier cliff, the Grand Wall is a must-do for any trad climber. And since almost no one does this Canadian classic all-free, there’s no need to feel ashamed about the A0 asterisk on your ascent. In fact, the bolt ladder on pitch nine has a fixed boat rope that you can hand-over-hand up, merrily clipping bolts as you went. Scott Cosgrove and Annie Overlin found a way to bypass this ladder with a 5.13 variation in 2000, but most people today aid this pitch, as well as a short bolt ladder below the towering Split Pillar. (It should be noted that local strongman Sonnie Trotter says the free variation is “outstanding climbing in an even more outstanding position,” if you’re up for it.) Many also use a bit of aid, at least for rest, on the strenuous Perry’s Lieback offwidth; you can use slings for all of these A0 moves—no aider needed. For most climbers, the real free-climbing crux comes on the Sword, a 5.11a layback and crack pitch, where the hard parts are brief with good rests in between; if you pump out and hang for a moment, you’ll knock the grade down to about 5.10+.

For the full experience, continue another four pitches via Roman Chimneys (5.11d). Most climbers will be more than happy to call it good and escape via Bellygood Ledge.

South Buttress Right (5.11b / 5.10a, 7 pitches)

Mt. Moran, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming

South Buttress Right is the best free climb on Mt. Moran, the northernmost of the Teton giants. The route goes nowhere near the summit of the 12,605-foot peak—you rappel after finishing the seven-pitch climb—but it’s still a full backcountry experience. The most efficient approach is to canoe across Leigh Lake, and most climbers camp at the foot of the route for an early start.

You can cut this Teton classic down to size by liberally applying one of the best A0 techniques: a little help from the rope. After a couple of pitches of moderate alpine granite, the crux comes at an intimidating hanging corner, with a laser-cut undercling (often wet) and layback crack, with insufficient foot holds. But fixed pitons and tiny cams provide decent pro—or, if you’re so inclined, a chance to cop a rest or lean for the next hold with a kernmantle assist. Some of the wildest climbing of the route comes above the crux, on the easy but hyper-exposed Great Traverse and the two 5.9/5.10 pitches at the top. The last pitch is a 5.10 slab with poor bolts—even if you expect to A0 the crux, make sure the leader of this pitch is solid on 5.10.