Beyond the Bolt: The Past, Present, and Future of Yosemite Bouldering

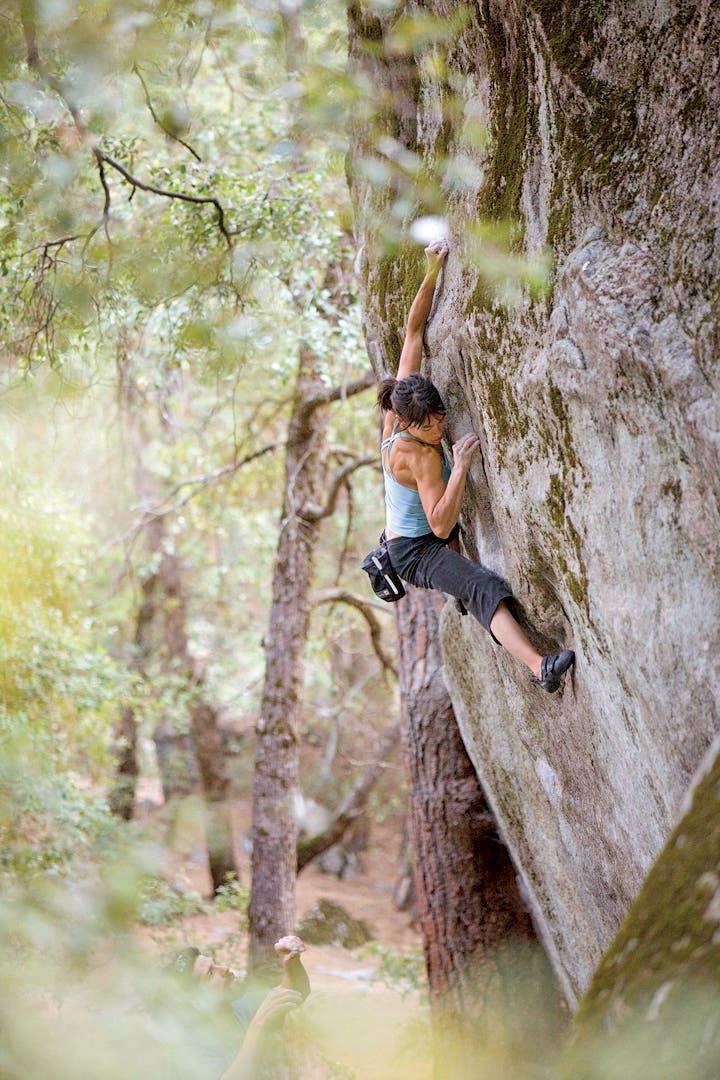

"Rich Crowder" (Photo: Rich Crowder)

Ed. The Yosemite Bouldering Guidebook has been released, in honor of the new guidebook we’re re-sharing this story by James Lucas about Yosemite bouldering and his time working on the book.

“I drew the original bolt on Midnight Lightning,” wrote John Bachar in a June 2007 SuperTopo forum post. “It was Yabo [John Yablonski] who actually ‘found’ Midnight Lightning. He was sitting in front of it one day and came over to me and Ron Kauk and said he found a new boulder problem. He said it would go. We laughed and said it was impossible. We thought there was about as much chance of doing it as there was the chance that a lightning bolt could strike at midnight (like in the Hendrix song ‘Midnight Lightning’)—so I drew a bolt on it in chalk. That’s it—pretty stupid, huh?”

In 1978, Ron Kauk jumped to a jagged edge—the “lightning bolt hold”—on the Columbia Boulder, a giant block in Camp 4. He matched, swung his feet across the wall, and threw his body into a committing mantel. Kauk pressed out the granite to complete the first ascent. Bachar soon followed. After finishing the problem, Bachar drew the bolt, cementing its iconic status. In the ensuing decades, Midnight Lightning became Yosemite’s “only” boulder problem—it eclipsed all others. And then for a week and a half in April 2013, the lightning bolt disappeared.

Below three-thousand-foot cliffs and massive waterfalls, amidst ponderosa pines and sequoias, amongst talus fields and forests, and covered in pine needles and moss carpets sit the quiet boulders of Yosemite. Five years ago, I started writing a new bouldering guidebook to the Valley, documenting its signature problems up smooth slabs, sharp cracks, rounded arêtes, and slick faces dotted with tiny crimps. As my friend Shannon Joslin, a Folsom, California, boulderer, and I tried to document both the history and the current development, new problems kept cropping up. All told, when our book comes out in 2018, it will feature more than 1,200 problems—1,199 more than the singular Midnight Lightning that’s become synonymous with Yosemite bouldering.

Yosemite’s bouldering history dates back at least to the late 1940s/early 1950s. Back then, Allen Steck, Royal Robbins, Yvon Chouinard, Jeff Foote, and Chuck Pratt established problems in Camp 4. They focused on mantels and slabs around the Columbia Boulder and the Wine Boulder, a similarly sized boulder a thousand feet north. They used the boulders around Camp 4 to train for the Sentinel, Half Dome, and El Capitan. The boulders became the lab for pin and head placements in the back of Camp 4, for bolt ladders on the LeConte Boulder, for chiseling footholds to access the Columbia Boulder’s west side, and later for reinforcing holds with glue in the ethical DMZ of the 1980/1990s.

In autumn 1963, Colorado climber Layton Kor snagged one of the Camp 4 plums when he climbed a smooth wall of green streaks northwest of the parking lot. The Kor Problem, today given V3, became a test to see if big-wall climbers were ready for the larger routes. Five years later, Pat Ament climbed an arête next to the Yosemite Falls Trail—the Ament Arête (V4). With a history in gymnastics, Ament brought chalk to the Valley, an idea that helped revolutionize the climbing game. The men climbed in Spiders and Kronhoeffers, far cries from modern sticky-rubber shoes. Nonetheless, in 1968, Ament climbed a smooth face right of Ament Arête. It was repeated a few years later by Ron Kauk, named the Kauk Slab, and later graded V8.

In the 1970s, Dale Bard, John Long, Mike Graham, Bachar, and Kauk pushed the difficulty further. Classics around Camp 4 like the slab eliminate Blue Suede Shoes (V5), Battle of the Bulge (V6), and the highball Shiver Me Timbers (V5) were all established. The boulderers began a slow progression beyond Camp 4. Bard walked to the south side of the Valley below the Sentinel where he developed the house-sized B1 Boulder. Sans pad, Bard put up No Holds Bard (V7), an 18-foot line of crimps over a flat dirt landing. Bachar walked to Housekeeping Camp and established Purple Barrel (V7), and later Crossroads Moe (V6) near Bridalveil Falls. These men, part of a core crew of Southern California climbers later dubbed the Stonemasters, pioneered free climbing in the United States in the 1970s and the 1980s. Most of their bouldering revolved around getting fit for the longer climbs. “We did it for training. There was no gym,” Bard said of doing hand traverses near Swan Slab, a few minutes from Camp 4.

Standards were slowly pushed. In 1984, Kauk added Thriller (V10), a highball line of crimps up a looming face in Camp 4. In 1991, Moffatt added The Force (V11), a few feet left of Thriller. However, a hold was reinforced on the problem. “There was so much glue you weren’t even grabbing the hold—just glue,” Bachar wrote in a 2009 SuperTopo post. Bachar, ever the purist, then “used my nail clipper file thing to pry the hold off.” In 1993, Moffatt skipped on climbing the Nose with Kurt Albert and instead linked a series of flat edges on the back of the Wine Boulder, establishing Dominator as the benchmark V12. Tellingly, in terms of how compressed/sandbagged bouldering grades are in Yosemite, only a few problems harder than “V12” have been established since.

“If I cleaned it, I wanted to do it first,” Yosemite bouldering pioneer Rick Cashner said. In the 1990s, El Portal resident Ken Yager turned Cashner on to a treasure trove of a dozen boulders below the Cathedral Spires. The thing was, Cashner wasn’t ready to share it until he’d picked the plum lines. “It was my secret,” Cashner said. Yager returned to the boulders with Dean Potter, and the pair saw Cashner’s chalk. Potter began climbing there with Cashner, and together the two developed most of the problems. As they walked to the trailhead, the men would cover their faces with one hand so as not to be recognized by climbers driving by. However, keeping any climbing area secret, especially in a geographically and socially small community like the Valley’s, can be nearly impossible.

One day in late 1996/early ‘97, Cashner and Potter saw a couple of unknown cars at the Cathedral trailhead. At the King Boulder, the centerpiece of the Cathedral Boulders, they saw Kauk, video camera in hand, taping Moffatt on one of Potter’s projects. “He was kind of burning us off,” Cashner said of his friend Moffatt “stealing the ascent.” After the incident, they named the problem Behave (V8).

A lot of these new finds were established in the pre-pad era, like So Good (V5) at Cathedral, the Generation Boulder on the west end of the Valley, and the Woodyard Arête (V6). First ascentionists developed the problems on toprope and then later “free soloed” them. In some cases, a little landscaping went on, including the buried pallet below the base of the Thriller Boulder. As pads came into the Valley, Cashner and Potter began using them. “We used to boulder, and it felt like cheating when we had a towel to wipe our feet off,” Cashner says. “Now I go there and feel naked without all my crashpads.”

In the past decade, pads have allowed climbers to push heights. In 2009, Randy Puro dropped six pads below Ron Kauk’s 30-foot two-bolt 5.13c, Two Bolts or Not to Be, and bouldered it out. Puro also bouldered out Ben Moon’s Happy Isles problem Egyptian (V10), which had been an obscure toprope for decades. In 2010, Dean Potter dropped pads below the LeConte Boulder, climbing the 40-foot King Air (V10), an arête sandwiched between two practice aid climbs. In 2015, National Park Service employee Keenan Takahashi sent the 30-foot Zephyr (V12) at the Crumbs below the Cookie Cliff. While the crux comes low, a slopey V7 arête with your heels 25 feet above the landing guards the summit. “I did Evilution the month before, and Zephyr was way scarier,” says Takahashi. As Bay Area boulderer and Yosemite climber of 20 years Paul Barraza says, “Bouldering didn’t really get that much safer with pads; people just went higher up. It’s an arms-race kind of thing.” Highballing in Yosemite has become so extreme that, in 2017, Alex Honnold even bouldered out the Freerider, a 3,000-foot V7 on the south face of El Capitan.

“It’s my turn,” Lucho Rivera said, grabbing the holds on a 15-foot arête. It was 2005, and we’d heard about new development in the woods below the Lost Brother. Here, in 1998, Marcos Nunez had climbed Don’t Believe the Hype, an immaculate 5.11 corner. Matt Wilder, who was updating the old Don Reid bouldering guidebook, and others were brushing off new problems and calling the area Candyland. In the end, it would yield 50 new problems. After seeing the arête, my friends and I started climbing on top of each other. Lucho sorted the opening moves. Zach Romero brushed holds. Lichen sprinkled on my head as they scrubbed while I climbed. I grabbed a crimp and made a big move to a jug on the arête. I stuck it. My feet pedaled on the dirty granite as I continued to the top, ecstatic.

I had started bouldering in 2001 as an employee at the Yosemite Lodge. I’d make beds and then would climb on the moderate problems of Curry just a 10-minute walk from my tent-cabin door. I had a copy of Don Reid’s second-edition guide to the boulders, which included over 500 boulder problems. My perception, much like that of the early Yosemite climbers, was that the bouldering was secondary to the routes. I’d climb on the cracks that split the modest boulders below Staircase Falls, and on the Horse Trail. I dreamed of climbing Jason Campbell’s tight-hands Lost Brother testpiece Deliverance (V8) or Potter’s heinously pin-scarred Sasquatch (V11) on the LeConte Boulder, or even thrashing through Cedar Wright’s riverside 30-foot offwidth roof crack Cedar Eater (V5). Sometimes, I’d venture onto faces. As I spent more time in the Valley, I came to realize that the boulders were “bigger” than El Cap, in the sense that most were harder to get up.

“If a tourist hit the gas pedal wrong, they’d run into the damn thing,” Barraza jokes of the “hidden in plain sight” Wall to Wall Carpet, a line of crimps, slopers, and athletic moves between two moss streaks 100 feet from the Bridalveil Falls Parking lot. In 2005, the Bay Area crew—Scott Frye, Tim Medina, Justin Alarcon, Scott Chandler, Puro, and others—started BetaBase, a website to document their ascents. They scrubbed the blocs around the Ahwahnee, the Horse Trail, and Bridalveil, establishing classics like El Rey (V12), Drive On (V10), and Junebug (V12). Barraza alone cleaned and climbed over 50 FAs. Puro and the rest of the Betabase crew added hundreds of problems, climbing with a new-school style, ditching the slabs and mantels for pogos, big throws, and wild slaps.

While the Beta Base crew developed the west end, Colton Lindeman, Ryan Alonzo, and other concession employees walked into the woods on the east end below Half Dome. The construction of 27 new one- and two-story employee-housing buildings in the middle of the Curry Boulders spurred remote development. Lindeman and Alonzo established 100 problems around Mirror Lake and Happy Isles, climbing moderates like Stem Money (V2), Slab Money (V5), and with Lindeman climbing the highball Bell Tower (V5). They showed the breadth of potential in the Valley still, even in the moderate grades.

In 2011, I began collecting data for a new book, working with my friend Shannon. However, as we poked along, keeping up with development began to feel impossible. Moreover, many Yosemite locals were less than enthusiastic about a new guide. In 2014, 3.8 million people, the 20-year average, visited Yosemite; in 2015, visitation was 7.3 percent above average; and, in 2016, visitation was 30 percent above average. The number of climbers in the park increased every year as well, meaning that once-secluded “locals’” boulders now saw more pads beneath them, further erosion, and higher traffic.

On April 1, 2013, I walked my friend’s dog Kuna from Yosemite Village, where I was housesitting for a park ranger, to Camp 4. I carried a spray bottle and a brush.

Every year, hundreds of climbers paw the starting holds on Midnight Lightning. Every year, Kauk and other ascentionists redraw the lightning bolt. Climber-tourists gawk at the problem, taking pictures of the bolt and posing on the first move, polishing the start. Weather ruins the bolt, leaving streak marks. Though the current generation tries to adhere to a Leave No Trace ethic, the graffiti on the Columbia remains. In 1976, Bachar and fellow Stonemaster Dean Fidelman pierced their ears in Estes Park, Colorado, with lightning-bolt earrings. Bachar drew the bolts “wherever we went,” Fidelman says, “So everyone would know that we were Stonemasters.” Imagine if Bachar drew a design on the Columbia today—if, instead of listening to Hendrix and drawing a lightning bolt, he rocked out to Katy Perry and drew a heart with an arrow through it. At 8 p.m., as I walked over to the Columbia Boulder with Kuna, spray bottle and brushes in hand, I came upon a random dirtbag sleeping underneath the boulder. “Are you erasing the bolt?” he asked. “Yep,” I responded. He went back to sleep, apathetic.

For a week and a half, the bolt disappeared and the Valley remained quiet. Cruz McClean, a climber from the Eastside, redrew the bolt. There was no mention of the bolt’s disappearance—until I wrote a blog about erasing it. Climbers from across the globe became immediately incensed. They felt ownership over a doodle chalked onto the stone. It was as if someone had turned a lever and shut off the faucet that feeds Yosemite Falls. I wondered if I should go into hiding, like Salman Rushdie after writing The Satanic Verses.

For many in Yosemite, there’s a belief that the Valley should stick to old ideals, keeping decades-old chalk graffiti or sandbagged ratings. Problems like Mr. Pink Eyes (V0), Initial Friction (V1), No Holds Bard (V7), Midnight Lightning (V8), and Thriller (V10) feel hard, if not impossible, for their grades. And there seems to be an unspoken agreement that nothing, ever, should be rated higher than V12, even if it really is. (Though earlier this year, visiting climber Jimmy Webb established Happier Days, a short roof project by Happy Isles, daring to call it V13.) “Yosemite has a history of underplaying the difficulty of things, which keeps them from getting that popular,” says Tommy Caldwell, who has added a few boulder problems of his own, including Yabo Roof, a long undercling roof to highball finish between Camp 4 and El Capitan. “It’s one of these places that you get the Bay Area crew, you get all the trad climbers that go bouldering a little bit, but you don’t get much of the international bouldering crew.” Perhaps it’s all the red tape of staying in the Valley, or, says Caldwell, perhaps it’s the technical style—but in any case, “It’s not a good place to go résumé-build.”

“If you do this problem in three tries, you can write the guidebook,” Beth Rodden said to me in Camp 4 in March 2016. Rodden, like other locals, didn’t want my guidebook to happen. A Valley bouldering aficionado herself, she’d established one of Yosemite’s hardest slab problems, Avocado (V8), a line of micro-crimps and smears up a remote boulder above Half Dome Village (formerly Curry Village). She feared the influx of climbing tourists.

Rodden, Randy Puro, and I were in Camp 4, playing with two sloping holds that marked both the beginning and the end of an unnamed problem just left of the Pratt Mantel, on Bard’s Flying Traverse Boulder. Two weeks earlier, I’d accepted a job at Climbing Magazine, which meant a steady paycheck, a move to Boulder, Colorado, and a drastic change from my 15 years of climbing across California. I was back in the Valley to boulder and to grab a few boxes I’d left in storage.

“Do you think it’s the end of an era?” Puro asked me, pawing at the holds and trying to press them out while Rodden watched. He fell. A New Mexico native and founder of Good Eggs, a Bay Area company that develops apps for food producers, Puro was also a master at mantels. He’d made the first ascent of the Pit Stop Mantel, a single-move V9 just down the trail. More than anyone in the Valley, Puro had pushed Yosemite bouldering, putting up dozens of double-digit problems. His struggle didn’t bode well for me. When it was my turn, I couldn’t even lift my feet off the ground. Puro fired the problem then explained how I should turn my hand. My second try, I could have almost passed a sheet of paper between my feet and the ground. Almost. I rested, and thought about his question.

I was unsure. Before accepting the job, I’d planned on spending the rest of the year in Yosemite, finishing the guidebook. I loved Yosemite but also knew that I needed to leave to grow—to escape the dirtbag lifestyle, to move beyond my obsession with granite walls, to leave behind festering in the ditch. Carlo Traversi, who established Cold Snap and Sideswiped, both Yosemite V12s, once told me, “Ultimately, the boulders of Yosemite will always be stepping stones for overcoming new challenges on the walls.” Now, as I pondered this mantel, I thought that Traversi’s framing of the subject felt antiquated—the bouldering here has grown to be more than just training.

Yosemite’s technical slabs, arêtes, and faces differ from the current “cutting edge” of global bouldering. Problems here lack big grades, the big holds and gym-style movement, and the convenient camping of the big-ticket destinations, like Hueco and Rocklands. But perhaps there could be a resurgence, a move back toward aesthetic lines, delicate movement, and rich experiences, to the singular style of climbing that makes Yosemite so magical. Perhaps the Valley could be about more than just the cliffs; perhaps it holds the future of climbing movement. On the southwest side of the Columbia Boulder is a barely-there arête, there are projects on the Yabo Roof boulder, and the house-sized boulder at Candyland and the Hotel Boulder at the Sentinel both have potential for the near-impossible. Beyond the existing projects, other futuristic offerings await exploratory boulderers in Tenaya Canyon, around Happy Isles, and toward Yosemite West, with potential for V15 glassy slabs and suicidal, 40-foot V13 arêtes—although they’d all, of course, be rated “V12.”

“One more try,” Rodden said. I gulped, turned my hand sideways, and felt my feet come slightly off the ground. When I felt the space between my shoes and the pine needles, I summoned a demon into my triceps. I pushed and pushed and pushed. My foot matched next to my hands and I stood on the dirty slab. I scrambled to the top, elated at my effort.

“Good job, James!” Randy said.

Yosemite Bouldering Logistics

Directions

Yosemite National Park is open all year, but the northeastern entrance, Highway 120 west over Tioga Pass, can be closed from November to May due to snow. There are three other entrances: Highway 120 east, Highway 140 east, or Highway 41 North. YARTS offers a bus service from major cities outside the park for those flying into Fresno, Sacramento, or San Francisco. In the park, a shuttle bus provides transportation close to most of the bouldering destinations.

Camping

Yosemite features a few different options for visitors, with 13 campgrounds; some are reservable and others, like Camp 4, operate on a first-come, first-serve basis. Visit recreation.gov to make reservations, join the long early-morning line at Camp 4 for a spot in the historic climber campground, or drop $560 a night to stay 500 feet from the Ahwahnee Boulders at the Majestic Hotel.

Season

The boulders in Yosemite are climbable year-round, though the middle of summer can be hot and filled with tourists even on the south side of the Valley. November through March offer the best conditions, though it can be wet. October through early December and late February through early April offer the best windows.

Amenities

The Yosemite Village store offers food and groceries, with everything from malt liquor to organic produce. On the west end of the Valley, Half Dome Village, by the Curry Boulders, provides a showering facility for $5. The nearest gas station is 14 miles away in El Portal, out the West Entrance, and usually costs $1 more per gallon than the average. Crane Flat, 16 miles away, and the Wawona Gas Station, 27 miles away, also offer overpriced gas. It’s best to fuel up outside the park. The Yosemite Lodge, Half Dome Village, and the library offer Internet.

Guidebooks

Shannon Joslin, Kimbrough Moore, and I created the Yosemite Bouldering Guidebook, available for purchase online and in stores in and around the Valley. Matt Wilder’s Yosemite Valley Bouldering, published by SuperTopo, will also be available in the Mountain Shop in Half Dome Village.

5 Yosemite Bouldering Gear Essentials

Organic Lunch Bag Chalk Bucket

The more chalk the merrier on slippery granite, which is why it’s nice to have a portable, roll-top-closure bucket like this to hold multiple blocks of precious powder. You also get double brush holders and a zipper pocket perfect for skin-care essentials like tape, super glue, nail clippers, etc. $33, organicclimbing.com

Petzl Reactik

For night bouldering, the rechargeable Reactik has 220 lumens and a sensor that automatically adjusts to ambient lighting—perfect for moving in and out of shadows cast by lanterns. $84, petzl.com

Stick Brush

Pretty much what it sounds like: a brush on a stick for cleaning hard-to-reach holds. Go caveman with a stick from the forest, adhesive tape, and a toothbrush, or take a tent pole and tape your brush to it to make an extendable rig.

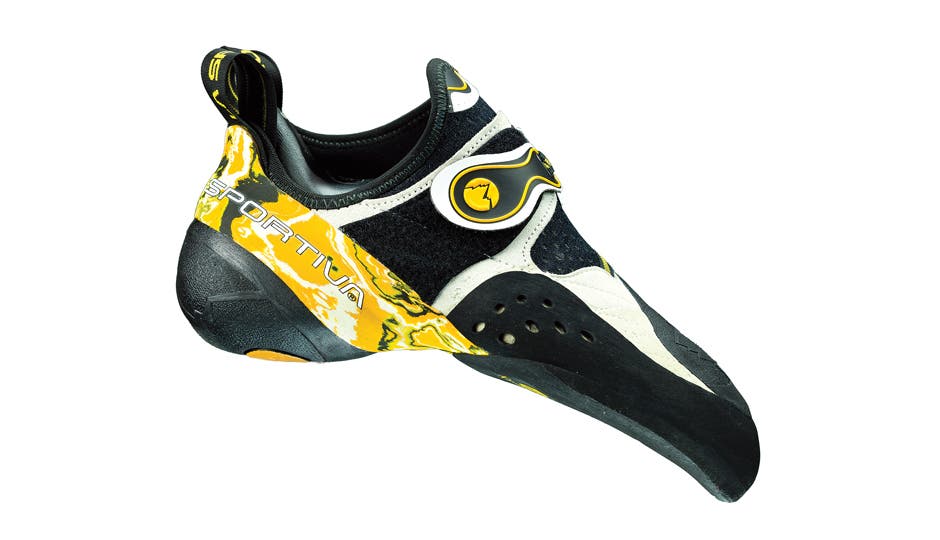

La Sportiva Solution

Valley bouldering is all about precision: digging into micro-edges and miniscule divots. You want an aggressive shoe that can edge and smear, like the radically downturned Solution, with its molded heel cup, ample toe patch, and P3 Power Platform. $180, sportiva.com

Sony A6000 with 16–50mm lens

If a boulderer sends and no one’s around to witness, did it really happen? Ponder no longer with this compact 24.3 MP digital camera, perfect for pix of your friend “flashing” the first move of Midnight Lightning. $550, sony.com