When You're Hungry for Rock, Buy a Cliff: The Sandstone Smorgasbord of Denny Cove

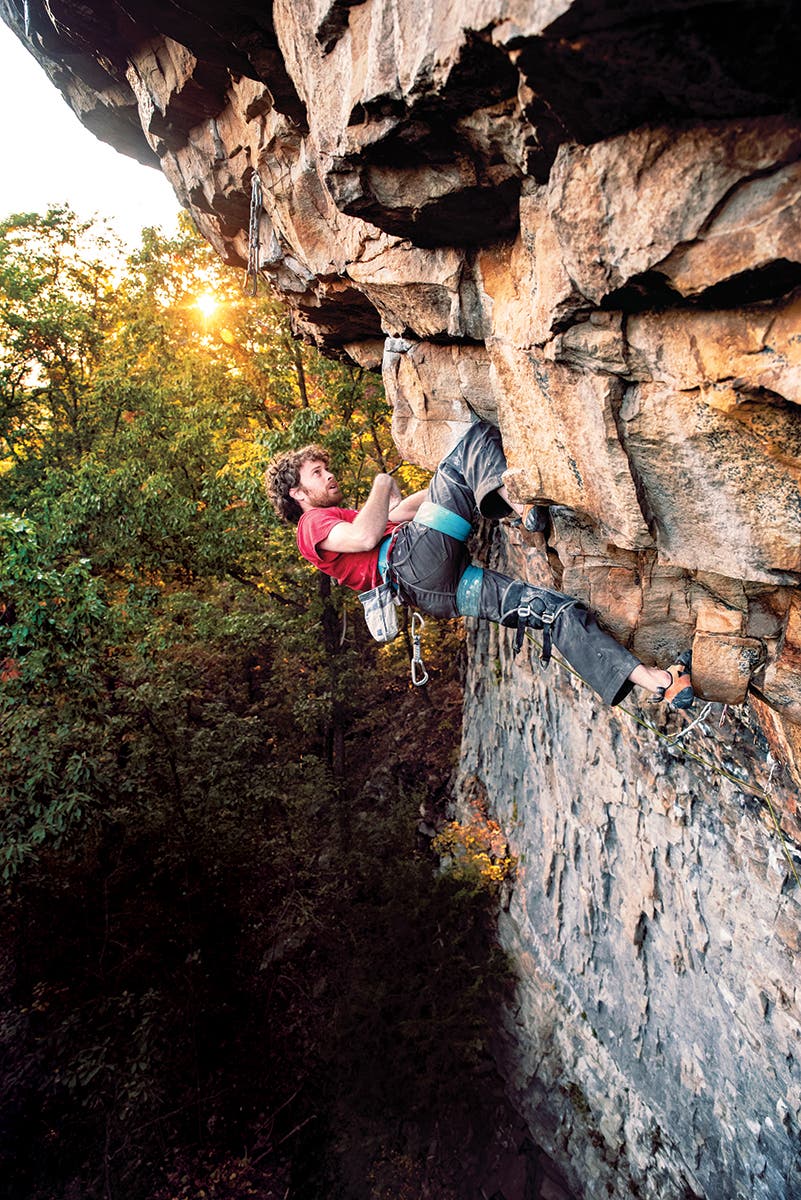

Cody Roney cools down on Three Star Salad Bar (5.10a). Roney was executive director of the Southeastern Climbers Coalition during the arduous process from 2012–2016 of establishing public access to Denny Cove. Thanks to her efforts and those of others, the crag has been permanently preserved. (Photo: Nathalie DuPre)

“What do you think?” my friend Max Barron asked as we walked the final trail meandering up to the Buffet Wall at Denny Cove, Tennessee. I gazed forward and saw a giant grin stretch across his face. Behind him was an 80-foot cliff looming over a swath of cedars, its giant sandstone visage unbroken for over 200 feet horizontally. I felt my heart skip a beat.

Buffet Wall is the most treasured wall among over a dozen sectors at Denny Cove, an area 35 miles from Chattanooga that was formerly on land owned by an international timber company. Since summer 2016—thanks to four years of tireless efforts by local climbers, the Southeastern Climbers Coalition (SCC), and the Access Fund (AF)—the area has been open to the public as part of the South Cumberland State Park system. Denny Cove has over 150 routes along its three-mile cliffline, with more being developed under permit approval. From 5.7 to 5.14, vert faces to overhangs, there is something here for everyone.

Most Southeastern sandstone crags look similar—deceivingly steep rock with intermingled hues of ocher and beige engulfed by a deciduous forest. If I were blindfolded and carried out to any undeveloped holler or cove, it would be hard to tell if I was in Alabama, Tennessee, or West Virginia. These Nuttall and Warren Point sandstone edifices and amphitheaters tend to resemble one another, with the exception of the occasional waterfall, rusted miner’s tools, talus field, or river gorge below.

But the Buffet Wall at Denny Cove is different. It morphs together in a surplus of sidepull shelves. Its lower layer comprises softer gray rock with tufa-like flake features comparable to limestone. About seven bolts up, the wall blushes with an orange complexion before finally revealing a darker band of bulletproof cocoa-colored rock where you typically find the cruxes of its 40 routes (5.11–5.14) as you crimp along steep seams.

While admiring the wall for the first time with Max in April 2018, I could picture the process: Paddling up jugs, getting into the flow, impending forearm pump, and then BAM! A steep, Southern-sandstone throwdown a few bulges beneath the anchors, leaving you in a stupefied hangdog state.

Buffet Wall became my refuge amid the unpredictable Southeast weather. If there’s one thing I’ve learned from cutting my teeth on Chattanooga stone for over four years, it’s that prime conditions are an anomaly. Nevertheless, I’d climb my projects in the dead of summer when the Buffet Wall was shrouded in afternoon shade, even though rattlers and poison ivy peeped through the talus below. And I climbed during torrential downpours thanks to the wall’s capstone roof. On one trip, my friend Kenny and I drove in through thick blankets of fog as we questioned our decision to climb. A few hours later, as tendrils of mist wafted up the wall, Kenny sent Meat and Three (5.12d/13a), an endurance haul with a big move to a tiny gaston guarding a double-kneebar rest above.

Denny Cove is even a great winter zone, thanks to its southern exposure: On February 14, 2019, I redpointed my proudest Buffet Wall send, The Mighty Quinn (5.13a), on a chilly afternoon. Then, for the rest of the year, I called Quinn “my Valentine.”

“You can go there and focus on your projects and routes, but really Denny Cove is bigger than that,” says Zachary Lesch-Huie, the Access Fund’s Southeast regional director, based in Chattanooga. “It’s an inspirational story about what we can do as a climbing community when we plan years in advance to protect special areas.”

Not even Google Earth, the most common way to find new crags in Chattanooga, could uncover Sequatchie Valley’s Denny Cove. Thick canopies of bigleaf magnolias, giant oaks, pines, and hundred-year-old cedars shrouded the sandstone escarpments from the gaze of satellites. Local developer Cody Averbeck received a tip from one of South Cumberland’s park rangers to explore the area only a half-mile from Foster Falls. Months later, after bolting Denny Cove with friends Steven Farmer, John Dorough, Dave Wilson, Edward Yates, and Anthony Meeks, Averbeck introduced the idea of preserving the land on a conference call with the SCC, AF, and several Tennessee organizations in 2011.

Shortly thereafter, Lesch-Huie moved to Chattanooga and continued the four-year fight for public access to Denny alongside the SCC’s then executive director Cody Roney. The Southeast is blessed with an abundance of cliffs, yet also cursed with issues around private-land access. Without these initiatives, Denny Cove would have forever remained one of many “secret spots” reserved for a handful of climbers and developers.

“Climbers haven’t often bought a piece of land worth nearly 1.3 million dollars,” explains Lesch-Huie. “It almost didn’t happen, but we realized at a point we had enough funders and partners to get us over the threshold.” Together, Lesch-Huie, Roney, and other organizers labored through endless meetings, phone calls, and discussions persuading funders to preserve Denny. Meanwhile, Averbeck and fellow developers continued bolting and cleaning the steep cliffs with permission from the landowner. By the end of 2015, Denny Cove had received over $1.1 million from local foundations, grants, climbing gyms, and organizations to cover the initial payment. This left a $150,000 AF loan for the SCC to pay off through fundraising after a ribbon-cutting ceremony in January 2016. For the next six months, Denny was open to climbing only during SCC trail days before the property transferred to the state.

Opening Denny Cove to the public meant the at-times-overwhelming crowds at nearby Foster Falls and Castle Rock could be spread out across the new zone. Today, the South Cumberland State Park system manages Denny’s 685 acres as part of 30,845 acres of protected forest, and its freshly built trails cater to climbers, hikers, runners, birdwatchers, and families alike.

To visiting climbers, Chattanooga is best known for its bulletproof bouldering on friction-dependent slopers. However, since Denny Cove’s access success story, the city has also seen a swell of roped climbers sojourning to explore Denny Cove, Laurel Falls, Tennessee Wall, and the other local crags. To put an economic point on it, climbing brings $7 million to Hamilton County each year, according to a 2016 study by the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

Denny Cove was discovered only in 2011, yet a decade later it’s hard to imagine Chattanooga climbing without it. At the close of 2020, the SCC completed the final $21,500 land-loan payment to the AF. Meanwhile, the coalition continues organizing trail days and new-route proposals with the Cumberland State Park. Route development must be approved by the park’s Fixed Hardware Review Committee to assure climber safety, quality hardware installation, and low environmental impact. Visitors can view crag beta on Rakkup or the newest edition of Rockery Press’s Chatt Steel guidebook.

There is much to be grateful for now that Denny Cove is open. Area testpieces include Little Tokyo (5.13d), Rockstar (5.13b), Lucid Dreaming (5.14a), and Cobra Pimp (5.14a). Cobra Pimp’s burly steep face and dyno right before the chains have befuddled many; it has still only seen a couple of ascents. The Buffet Wall is now Chattanooga’s most concentrated 5.12 wall, with over 20 routes of the grade. Downhill a few yards, the Salad Bar serves up a handful of aesthetic 5.9 and 5.10 moderates. These face climbs, painted in bright-orange lichen, offer scenic views of the cove around you.

Thanks to Denny Cove, my climbing partners and I have a bountiful sandstone smorgasbord right at our fingertips. But there is still a lifetime of access work to be accomplished near Chattanooga. As big and boast-worthy as the new crag might be, Denny Cove is a mere appetizer compared to the buffet of routes and boulders—both prospective and already developed—needing to be preserved in the Cumberland Plateau.

Elaine Elliott is a freelance copywriter in Chattanooga, TN. She is founder and director of the media platform Steep South, which promotes climbing stories and access efforts through Instagram, articles, and short films.

Economic-impact source: accessfund.org/news-and-events/news/denny-cove-in-tn-preserved-and-opened-to-climbing.