Dirty Dingus McGee and the Reese Mountain Gang

"HPDingus"

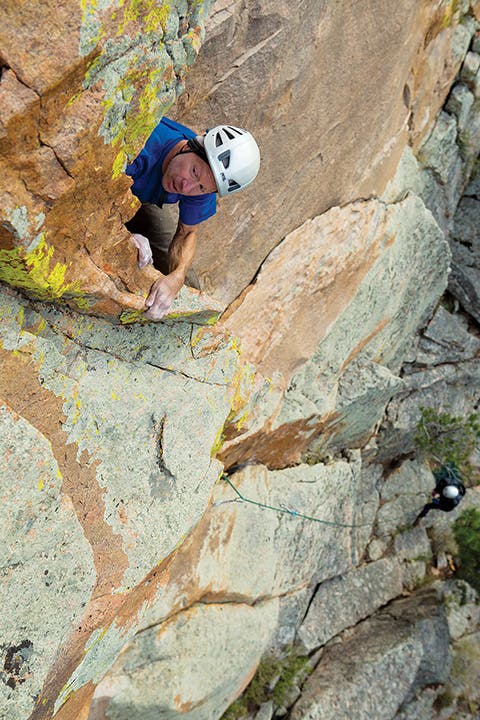

Dingus McGee had sent me written directions and three separate maps to Reese Mountain, but when we drove onto the Vale Ranch in Wyoming’s Laramie Mountains last September, already layered in dust from 15 miles of dirt roads, we quickly lost our way. A maze of ranch roads twisted through the grass like Land Rover tracks across the African veldt. In the distance, studying Dingus’ photos, we recognized the long ridge of Reese Mountain, where he and his posse have put up about 200 routes during the past two decades. But how were we supposed to get there?

Dingus had said Reese held the best sport climbing he’d ever done—and he’s put up more new routes in eastern Wyoming and South Dakota than any man alive. His photos revealed a striking fin of gray, green, and red rock, like a granite version of Eldorado Canyon in Colorado, but with better holds and plenty of bolts. Most of the routes are in the sweet spot for sport climbing popularity: 5.9 to mid-5.12. But Reese, we’d soon learn, presents many challenges unrelated to actual rock climbing. It took us an hour just to find the trailhead.

A faint trail plunged down a slippery wet draw through aspen and scrubby oaks. In the creekbed we pushed through thickets of poison ivy with glossy, scarlet leaves. (Reese climbers, we learned later, always hike to the crag in gaiters or rain pants, and then scrub their exposed skin with soap and water before climbing.) Bear shit lay in prodigious, berry-filled piles in the path. After more than an hour of walking, we climbed over a small ridge to a view of the crags, still 500 feet up a hillside. Suddenly the wind blew so hard that we staggered under our packs, loaded with food and gear for three days.

Within five minutes of reaching the lowest cliff, looking up and wondering which line of mystery bolts would make a good warm-up, I cartwheeled into the talus as a boulder rolled under my feet. As I gingerly checked for injuries, I was approached by a wiry, slightly stooped man. He had a silver beard and tangled hair poking out from under a ball cap and wore wire-rimmed glasses and a threadbare sweater. He looked us over. “You made it!” said Dingus McGee. He sounded surprised to see us.

I was beginning to sense why Dingus and his gang had decided to spill the beans on their long-secret enclave. Given what we’d experienced before even roping up, it seemed unlikely that Reese would soon be overrun with gym climbers.

Dingus McGee, née Dennis Horning, is one of America’s most prolific and enduring route developers. (Horning adopted the nickname from a 1970 film, “Dirty Dingus Magee,” starring Frank Sinatra. It’s a long story, and Dingus is more than happy to tell it, but it’d require a thousand-word detour.) Over more than 40 years, Horning has established or freed hundreds of routes at Devils Tower, the Black Hills of South Dakota, throughout southern Wyoming, and in other states. In the early 1980s, he was a pioneer of what eventually would be called sport climbing. And he’s still at it: Last winter, at age 65, he redpointed the first ascent of a 5.12 route at Guernsey State Park, a recently developed sport area in Wyoming.

Dingus is a born raconteur, telling stories in a high-pitched, singsong drawl, and his life has given him plenty of material. Growing up in Edgemont, South Dakota, (pop. 774) just south of the Black Hills, he was a bright, smart-ass kid who got in a lot of trouble without doing much real damage. When he was 17, Horning and some friends were jailed briefly for lobbing eggs at someone they thought had just egged them. “Well, that person was the new young police officer walking to work just after dusk,” he said. “Just after the jailing, a girl that had a crush on me showed up and offered to sneak some hamburgers through the small window. I asked for a hacksaw blade instead. They let everyone out when the 10 o’clock curfew whistle blew, and we never told anyone about the bar I’d sawn through in that cell.”

Horning discovered climbing in 1971 during a joy ride to Devils Tower on a new motorcycle. Ignoring the “Hiking Above Talus Requires a Permit” sign, he scrambled to the base of Hollywood and Vine(5.10c). It was obvious he couldn’t go farther without gear and knowledge, so he bought a how-to book at the visitor center. Back at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, where he was studying engineering, he asked local cavers where they bought their carabiners, and then sent an entire paycheck to Boulder Mountaineer (a gear shop in Boulder, Colorado, now closed) to order gear.

The Black Hills held the closest rock to campus, and Horning dragged friends out to the Needles, Mt. Rushmore, and Elkhorn Mountain, climbing whatever looked good. There was no real guidebook and precious few climbers in the area. Most of the routes he did were probably new.

Horning was a good athlete—he later competed in Nordic skiing and wrote mountain biking guidebooks—but it wasn’t just the physical side of climbing that appealed to him. He was an engineer and liked to make stuff. (He learned to make homebrew when he was just 14—with his parents’ permission—and at the tipi camp outside Devils Tower National Monument, where climbers used to crash in the ’80s, he constructed a bicycle-powered device to grind wheat for pancakes.) Making new routes naturally followed. “He might be the most prolific first ascensionist ever in the Black Hills, probably even more than Herb and Jan Conn [the original pioneers of Black Hills climbing],” said Brent Kertzman, a longtime climber from Rapid City, South Dakota.

During his first year of climbing, Horning spotted a group of climbers on a pinnacle in the Black Hills. It turned out to be Tom Higgins, Bob Kamps, Mark Powell, and Dave Rearick, four of the strongest free climbers of the day. “They befriended me immediately, and the next few days I climbed with them and learned a lot, including their ideas of what would later be called climbing ethics,” Horning said. “So I learned from the traddest of the trad,” Horning said. He paused for a beat: “I guess it didn’t catch.” He also later met bouldering legend John Gill in the Needles.

Without much concern for what other climbers thought—at a time when most new routes were still established ground-up—Horning began experimenting with rappelling to place bolts. “Doing new routes for me is a creative undertaking that makes use of several of my skill sets,” Horning explained. “But by the time I met Kamps and that group at the Needles, I had my own ideas as to what constitutes safety and fun. When you climb a new line, you are in control of the outcome, and I had several convictions of what I wanted out of a climb. Boldness and runouts never had much merit for me. If I did a climb, I wanted some 99.9 percent likelihood I would be around for another.”

Horning said he “came out of the closet” about his top-down tactics in 1981, and in 1983 he rap-bolted the second pitch of Everlasting (5.10c) at Devils Tower, while doing the first ascent. “Locals were furious,” he said. “But I put up a third of the routes at the Tower. I was more local than anyone!” (In fact, Horning put up or freed about a quarter of the routes in the Devils Tower guidebook, including many favorites: Assembly Line (5.9), Burning Daylight (5.10b), One-Way Sunset (5.10c), Mr. Clean (5.11a), the first free ascent of McCarthy North Face (5.11a), and, of course, Everlasting.)

“Back in the ’70s, I was a ranger at the Tower, and Dennis was on the South Dakota Climbing Team, which means he was on unemployment for the summer,” said longtime partner and friend Frank Sanders (see Under the Devil’s Spell). “Dennis definitely raised free climbing standards on the Tower.” Horning and his ex-wife, Hollis Marriott, popularized climbing at Devils Tower and the Black Hills through a long-running series of guidebooks, published under the pen names Dingus McGee and the Last Pioneer Woman. The Tower guide went through at least 14 editions.

Kertzman climbed many new routes with Dingus in the Black Hills, including some controversial rappel-bolted climbs in the early 1990s. Later, Kertzman said, “I decided there were better places to play that game, but Dennis would say, ‘Let’s stir up the hornet’s nest. Let’s see how long these routes will stand before they get chopped.’

“I call him the Howard Stern of southeastern Wyoming climbing,” Kertzman added. “He’s not worried about what other people think. And he was a harbinger of sorts—he understood climbing’s evolution.”

Dingus had enrolled in college to escape the draft and Vietnam, and he eventually chose mechanical engineering for a degree. However, he said, “Before I had finished three semesters working on my master’s, I discovered climbing. My foggy career goals soon became definite: I would rather be climbing than working at an engineer’s desk.” (He eventually did get a master’s and worked on a Ph.D., with the thesis topic “Using Lagrangian Coordinates to Model Shock Wave Propagation in Snow.”) Now he works just enough to get by, doing home remodeling and other building projects. Mostly he climbs.

In recent years, Horning and partners have developed dozens of routes in Harts Draw, a side canyon of Indian Creek, Utah; more than 100 routes at Guernsey, the lowest elevation and warmest winter climbing area in Wyoming; and about 60 routes on the limestone of 4 Stories, a summertime crag in the Snowy Range west of Laramie. Horning found Reese in the 1980s while perusing maps of the Laramie Mountains for mountain biking routes. He saw a cluster of contour lines and thought, I gotta check that out!

The southwest ridge of Reese Mountain is a granite fin that rises about 1,400 feet above winding Ashley Creek. Both sides of the ridge and its tip are laced with climbs. Because of the different sun and wind aspects, and who-knows-what geological influences, the rock and the climbing vary from crag to crag along the ridge.

The Hightower, at the low end of the ridge, has tricky sidepulls and edges, with a second tier of routes up an overhanging headwall. The Curl, around the right side, has chickenheads and incut edges. On the opposite side is the Amphitheater, a flat plane of gray overhanging rock. Higher up the ridge, Douglas Park, usually accessed by rappel from the ridge top, has overhanging slopers. Sherard Tower, near the top of the fin, has longer routes with slabs and roofs. Bolts are plentiful, and Horning and other climbers are rebolting their old routes to turn them into pure sport climbs or to reduce the possibility of ledge falls and other hazards. “We’ve crossed the River Styx between trad and sport,” Horning laughed. “I don’t want this to be a stick-clip area.”

“I’ve climbed at a lot of places, and steep, featured granite is pretty hard to find,” says Mike Friedrichs, a Salt Lake City climber who has been coming to Reese and developing new routes since about 1993. “City of Rocks comes the closest to what Reese is like. But it is coarse at times and doesn’t have the small-grain compactness of Reese granite.”

Like Friedrichs, many Reese climbers are part of a Wyoming diaspora—climbers who once lived or studied in the university town of Laramie but migrated elsewhere for work, or just to escape the wind, and now come back for homecomings at Reese and other favored crags. Ryan Laird, who now lives in Fort Collins, Colorado, says, “The remoteness and ruggedness of Reese provide a sense of solitude. The different sections of the ridge offer a huge variety of rock shapes and climbing styles: featured technical faces, four-pitch slabs, steep roofs, and even a few splitter cracks. It’s a special place.”

On our second day at Reese, we headed for The Curl with Friedrichs, Laird, and Anne Yeagle, another Reese climber now living in Utah, seeking the morning sun and some shelter from the sharp knife thrusts of Wyoming wind. We sampled a new route that Laird had just completed, brushing drill dust off the holds. Yeagle and Friedrichs led two 5.12a pitches, cranking positive edges over bulges. I climbed several 5.10 pitches that would be three stars anywhere in Colorado. Horning showed little inclination to shoe up. “That one’s beyond my hanging-on ability,” he said at one point. Instead, he directed traffic, telling the crew which routes they ought to climb for photographer Andrew Burr.

After lunch, I tried and failed to find the right sequence for the hand-jam and iron-cross crux of a wild 5.11 called Sex at Noon Taxes. Dingus, a fan of puns and palindromes, had coined that name. He is also prone to practical jokes and pranks. Once, when he felt a partner was lingering and chatting with other climbers for too long near the top of Devils Tower, Dingus rappelled off without him. Kertzman said every climbing trip he did with Dingus had a theme, usually involving flatulence or sex or human activities too perverse to describe in this magazine, upon which Horning would riff for days, sometimes in nasty ways, like a kid who doesn’t know when to stop teasing.

“I learned a lot from the guy, and he’s been inspirational, but in a kind of tormenting way,” said Kertzman. “He’s more of a tormentor than a mentor.”

Zach Orenczak, who has been climbing at Reese since 1998 and is about to publish a guidebook to the Laramie Mountains (see Beta section), said of Horning, “The steep routes of Reese were built by the blood, sweat, and tears of his many younger partners. Reese is Dennis’ Shangri-La, and when he’s out there, he’s the king. He rules with an iron fist and incredible punctuality. If you are not ready to hop in his van the moment he’s ready to roll, he’ll steal your route and name it Zachoff [Rendezvous Buttress, 5.11a]. At least he gives credit where credit is due.”

“Dennis can be irascible, petulant, and loves to argue,” Friedrichs said. “Some people just don’t want to be around him anymore. But Dennis also has a really caring side to him. One time a woman in Laramie was in an auto accident and was hurt pretty badly. Dennis showed up at her house and did chores for a couple of months until she was back on her feet. He’s given away more first ascents than most people ever have. I hadn’t known Dennis very long when he asked me if I wanted to do a first ascent at Devils Tower. He had cleaned the crack of poison ivy and placed a bolt, and he gave me the lead. I’ve seen him do that for a lot of people.

“Dennis is also interesting,” Friedrichs added. “He calls me at least a couple times a month to talk about string theory or nutrition—once, a long discourse on welding. It made me realize that you don’t have to stop learning when you get older.”

One veteran Wyoming climber calls Horning a cantankerous know-it-all. Another calls him a cherished friend. To many, it seems, he is both.

“One of my favorite stories is actually recounted by Dennis himself,” Laird said. “The family that lives next to Dennis once told their 6-year-old that he needed adult supervision to play outside. The kid thought about it for a minute and then asked, ‘Is Dennis an adult?’”

Late in the day, we hiked to the top of the southwest ridge, and Friedrichs, Yeagle, and I rappelled off the far side into Douglas Park. I climbed back out via Hanging of Yellowstone Kelly, a superb 5.11b with sequential cruxes between good rests. Friedrichs led the appropriately named Aeolus (5.12b), and then belayed on top with his coat snapping in the wind. “One time I couldn’t even throw the rope down to rappel to Douglas Park, the wind was so bad,” he said later. “I had to tie a pack to the rope to get it to go down.” The night before we arrived at Reese, the wind destroyed a brand-new tent.

“Is it always like this?” I asked Horning, hunched in the lee of a boulder.

“May and September are windy,” he said. “July is too hot. June and August are good.”

Reese is a bastion of Type 2 fun—activities that seem fun only after they’re over and you’re telling stories about them in the bar—which is undoubtedly part of the appeal for certain climbers. “I have had too many Reese experiences to count,” Laird said. “I have been baked, frozen, wind-whipped, and mosquito-bitten. I have experienced rain that soaked through my rain gear to my underwear, and forded flooded streams. I have seen deer, elk, bighorn sheep, rattlesnakes, and lynx. I’ve skinny-dipped and stomped out a brush fire, but not at the same time.”

In July 2002, Friedrichs and Yeagle hiked into Reese late at night during a fearsome lightning storm. “We sat on the rocks and watched an amazing show,” Friedrichs recalled. “The next morning there was a faint smell of smoke. Anne and I hiked around and climbed two pitches on Hightower. On top of the second pitch we saw smoke to the northwest. We headed back to camp and watched for about 15 minutes until flames came over the ridge two or three miles away. The flames were leaping from tree to tree. We packed up and left as fast as we could, and the fire eventually burned almost all the way around Reese. We were lucky the wind didn’t pick up.”

Rattlesnakes have been discovered at least twice at Camp Dingus, Horning’s favorite campsite atop the ridge. “We really like rattlesnakes, but not at camp,” Friedrichs said. “Dennis made a snare from a stick and a piece of twine, caught the snake, and put it in a five-gallon bucket. We put a lid on it, and Anne rappelled off the west side with the bucket clipped to her harness so she could let the snake go.”

In such an environment, it’s not surprising the Reese regulars do their best to ease the burden. When climbers are occupying Camp Dingus, hidden in a sandy patch amid the convoluted rocks on top of the ridge, a camouflage tarp keeps off the rain and sun, and a filter system provides drinking water from potholes filled by storms. The Reese crew stashes ropes and gear in strategic locations around the crags, and they stock mouse-proof thrift-store suitcases with cooking supplies and other necessities for return visits. This way, they can hike in for several days of climbing with a daypack weighing only 10 or 15 pounds. Entering Camp Dingus after scrambling up a gravelly gully and threading through rock passageways feels like you’ve stumbled into a guerrilla hideout. You expect to encounter armed sentries and trip wires.

Horning estimates he has spent more than a year of his life at Reese. One time he stayed there 18 days straight. Understandably, he’s a bit possessive. Twice, most recently in 2005, billionaire Pat Broe, who owns Notch Peak Ranch just to the north of Reese, tried to negotiate a land swap with federal officials that would have moved about 5,000 acres of land, including Reese Mountain, into his holdings. Horning helped rally opponents to the deal and kept Reese in public hands.

On day three the wind had lessened just a bit, and we walked around to the Amphitheater for two overhanging classics: Twenty Red Lights (5.11c) and Fading Into My Own Parade (5.12a/b). Looking up at the latter, Friedrichs said, “That route’s all 12b before you get to the 12b.” In late morning, Horning got inspired to climb. After a couple of us had done a long, tricky 5.10, Horning laced up, tied in, and floated the route. At 65, because of exercise-induced asthma, he no longer ski-races or bikes, but he’s plenty fit. “If you’re going to hike with Dennis, you better put your track shoes on,” Friedrichs said.

The Amphitheater had obvious room for new routes, likely very hard, but I wondered who would do them. There’s not much harder than 5.12b at Reese, and not much easier than 5.10. Given the isolation, the short season, the snakes, and the wind, even this article and the new guidebook are unlikely to lure hordes of sport climbers. Which will leave Reese Mountain to those who love it.

“Dingus first invited me to Reese about 15 years ago when he saw me climb the Left Torpedo Tube (5.10+) at Vedauwoo blindfolded,” said Laird. “Apparently he figured that if I liked climbing that much, then I would love the climbing at Reese. I’ve been trying to keep up with Dingus ever since. Reese is unique, and I love sharing the experience with other climbers and seeing how the place affects them.”

In early afternoon, facing a long drive home, I started to hike out from Reese alone. A rattlesnake buzzed by my feet as I followed the faint path up Duck Creek, and I got lost halfway to the car. But I knew I was one of those climbers who’d soon find his way back. //

The Dingus Dozen

The Reese Mountain Gang’s all-time favorites

(Commentary by Dennis Horning)

Red Mite (5.9+) The CurlGreat warm-up with chickenheads, bulges, rests, and an optional 5.10 finish.

Block Party (5.10c) Hightower150 feet of fun.

Rope Tricks (5.10d) HightowerPinches and gastons rule over crimps.

Mrs. Radical (5.11a) Douglas ParkHow good are you at slopers?

Ride Steppenwolf(5.11a/b) HightowerSidepulls, edges, and pinches for 140 feet on the upper wall.

Hanging of Yellowstone Kelly (5.11b) Douglas Park“The best 11b in all of Wyoming.”

Sport Trindleberg(5.11b) The CurlA steep wall to a delicate hip-shifter roof exit, with more fight to come on the face above.

Twenty Red Lights (5.11c) The AmphitheaterAn overhanging face not yet flashed by a Vedauwoo climber—they always go for the crack.

Gamma Bursts(5.11c) HightowerBurly moves on a double-overhanging dihedral.

Aeolus (5.12B) Douglas ParkLeft-trending crack and corner system. Spectacular stemming and arête moves.

Down Converter(5.12a) The CurlDifficult stemming finishes with a crimp at the exit shaped like a light switch in the “on” position. The first 80 feet to an anchor on the right is 5.10+ and excellent.

Fading Into My Own Parade (5.12a/b) The AmphitheaterFading will happen when your hands can’t feel to grip, toes too numb to step, and your boot heels are wanderin’. (Apologies to Bob Dylan.)

Beta

Get there Reese Mountain is in the Laramie Mountains, west of Wheatland, Wyoming. Allow about four hours of driving from Denver or eight hours from Salt Lake City. The last hour of the drive is along the gravel Tunnel Road and two-tracks across Vale Ranch; high-clearance vehicle recommended. The hike from the parking area at the top of Tony Gulch takes about 1.5 hours; the faint trail goes down Tony Gulch to Duck Creek and follows this to the confluence with Ashley Creek. Download GPS tracks for the drive across Vale Ranch and the hike here. Maps and other approach information are at mountainproject.com. Allow a few extra hours for the driving and hiking route-finding on your first visit.

Guidebook Zach Orenczak and his wife, Rachael Lynn, will release High Adventure in the Laramie Range: A Climber’s Guide ($50, extremeangles.com) in August. The book will cover Reese and many other crags accessed by Tunnel Road.

Camping There are good sites in the meadow below the crags (make sure you’re above private land at the junction of Ashley and Duck creeks; water may be hard to find in late summer). You can also camp on top of the crags; potholes hold water year-round (filtration mandatory).

Season The Reese Mountain window extends from May through September, with June and late August typically offering the best climbing, without being too scorchingly hot. Some roads may be difficult to pass in early season. Parts of the Laramie Peak Wildlife Habitat Management Area, including the approach to Reese Mountain, are closed to public access December 1 through April 30 to protect breeding bighorn sheep.

This article was originally published in Climbing in 2014.