Epic Proportions: New Routing on the Diamond.

mity Warme and her husband, Connor, on pitch 6 (5.11a) of the new-school classic Hearts and Arrows (V 5.12b) in August 2019. The Diamond, Longs Peak, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado. (Photo: Chris Weidner)

Gambler’s Fallacy

Nervous barely describes how on edge I feel.

I hang from an anchor more than halfway up the Diamond, the 900-foot-high panel of granite that crowns the vertiginous East Face of Longs Peak (14,259 feet), Colorado. It’s August 9, 2020, on my redpoint attempt of the nine-pitch 5.13 that Bruce Miller and I have worked for the past four summers. Above me loom the hardest pitches: a short, bolted 5.13b face (the “Sport Pitch”), an overhanging 5.12 crack, the technical “Roof Pitch” (5.13a), and the final, razor-thin 5.12d face and seam. I look up at the Sport Pitch’s overhanging face ripped with fingertip edges and miniature corners. After you clip four bolts, the pitch finishes on Table Ledge, a horizontal band splitting the upper two-thirds of the wall that, here, is a mere six inches wide.

Below, Bruce jugs the Winter Wall Dihedral, the Diamond’s most conspicuous feature from the north. And though it’s one of our route’s easier pitches, at 5.11d, my forearms swelled with a flash pump and my fingers and toes went numb on the lead. At 13,000-plus feet, the cold is ever-present, especially once the wall drops into late-morning shadow. Coupled with the five-mile, 4,000-foot-gain approach, vicious storms that blindside you, the short season, spots of loose rock, and seeping, sometimes ice-choked cracks, every day up here feels adventurous. Which is precisely what draws people to the Diamond—and Longs Peak—in the first place.

With its broad, distinctly flat summit, Longs dominates the view from the plains east of Colorado’s Front Range. The peak is attempted by more than 15,000 people annually (and summited by about half that), nearly all of whom hike up the circuitous Keyhole Route. Ever since its first ascent more than 60 years ago, the Diamond has been North America’s premier alpine-rock crucible. Routes like The Honeymoon Is Over (5.13c) and the Dunn-Westbay Direct (5.14b) have cemented its status as the hardest, highest free-climbing arena in the world. In the past 35-odd years, those two climbs, plus a host of other new lines from 5.11+ to 5.13, have not only intensified the allure of the Diamond, they’ve hinted at its promising future.

Bruce nears my stance, inspecting the gear for his own redpoint attempt. For now, he’s supporting me; his turn will come.Bruce Miller, a carpenter by trade in Boulder, is as badass as he is understated. Choose any random pitch—rock, ice, choss, snow-covered, runout—and he’ll get the rope up. His résumé includes world-class alpine routes, remote A4 big walls, global FAs, and a healthy dose of 5.13s. Best of all, he’s kindhearted, humble, and easygoing. Since 2003, when we first climbed together in Vedauwoo, Wyoming, we’ve had loads of fun, much in the mountains. This is our second new Diamond route, our first being Hearts and Arrows, a nine-pitch 5.12b we put up in 2010.

I exhale forcefully, passing the hand warmer back and forth in my chalk bag. I unclip from the belay and remind myself to be deliberate: no hesitation. Because it’s in those brief moments of indecision when the doubts appear, like a distant flash of lightning.

Almost exactly one year earlier, in August 2019, I stood at a small belay stance two pitches higher while Bruce rehearsed the crux pitch below on solo-toprope. Inky clouds and dark-gray streaks linking clouds to valleys hovered well to the north, so I didn’t worry: Only a 10 percent chance of storms was forecasted. But soon, a white flash blinded me, accompanied by a long, loud rumble. On Longs, clouds build up toward the west, invisible from the Diamond. In minutes, the cobalt sky can mutate into a swirling gray-black mass that can soak the wall with alarming ferocity—first with a violent battery of rain, hail, and snow, then by lighting it on fire. In July 2000, Andy Haberkorn was high on the Casual Route when lightning struck him in the chest and killed him. Being caught on the wall in an electrical storm is serious … and frightfully common.

Suddenly, heavy snow began to fall. Bruce and I yelled back and forth, we had to move, but which way—up or down?

Flash-KABOOM!!!

If down, we’d be sitting ducks at the end of our fixed lines, several hundred feet above Broadway, the big ledge dividing the Diamond from the Lower East Face. Or we could jumar to the top. But to jug fixed lines to a Fourteener’s exposed summit area during a storm … could anything be more foolish? It struck me that this might be the most important decision I would ever make.

“I’m going up!” I yelled to Bruce, jugging frantically. Heaving chest, cramping arms—I felt like I was on a speeding Treadwall with landmines for crashpads.

KABOOM!!!

Lightning struck the wall, then the Boulderfield, then the summit, illuminating the storm from within. Snow flew sideways, freezing my face. Pull-up after pull-up, faster and faster, heart might explode. I collapsed on a ledge 20 feet below the top, gasping, drenched from sweat and snow. Huddled against the cold stone, too afraid to move, I waited for Bruce as icy hail piled up around me.

Today, however, the weather is stable. Ten feet above the belay, I reach a niche in a roof and shake out, trying to rewarm my fingers. I go through the moves I’ve memorized, and what feels like seconds later I’m poised like a spring, zeroed in on Table Ledge. I uncoil and latch the edge, then maneuver a final, tricky stand-up. I’ve sent the hardest pitch.

Partway up the penultimate “Roof Pitch,” a wide stem offers a moment’s reprieve. I glance down more than 1,300 uninterrupted feet to the talus, yet I am calm. When Bruce and I first tried the roof in 2017 and 2018 we were gripped, even on toprope. With inadequate directionals, just getting on to try the moves would often result in terrifying swings into space. Ultimately, this 5.12-ish sequence demanded a tremendous amount of time and energy to decipher, relative to its difficulty.

I engage the roof with intensity. “Chris! You’re a boss!” I hear from afar as I pull the lip. It’s my friends Phil Gruber and Josh Wharton yelling from the left side of the wall. Higher, I tiptoe on micro-edges and non-holds, and then lurch for a sloping edge. A few more shaky moves and I highstep the belay ledge, gasping.

On the last ropelength, my body sags, heavy with fatigue, stress, and desire, just as my fingertips catch a toothy matchstick. My technique turns sloppy even as hope surges within. Finally, I pop my head over into the blinding sunshine. Four years and 51 days of effort have culminated in this moment; I feel it intensely. Soon, Bruce appears. I grab him, hug him hard, and thank him.

“It’s your turn now, brother,” I say.

Some History

As a climbing objective the Diamond was a late bloomer, remaining untouched even after much taller walls like Yosemite’s El Capitan had been climbed. “In 1960 the Diamond was the most famous unclimbed wall in North America,” wrote Dave Rearick in Alpinist No. 19. Several factors had repelled suitors, prime among them a climbing ban imposed by the Park Service in 1954 over fears of an accident and complicated rescue. But when two young Californians, Rearick and Bob Kamps, provided their own “rescue service” (thousands of feet of ropes and climbing buddies on hand), the park relented. In August 1960, over three days, the pair climbed a striking crack splitting the wall. Given VI 5.7 A4, Ace of Diamonds (now known as D1) was one of the most difficult aid routes of its time.

By the early 1970s, the Diamond had become Colorado’s most alluring free-climbing prize. In 1975, Wayne Goss and Jamie Logan freed the wall via Komito Freeway (IV 5.10), a meandering line on the left side that combined several aid routes. It’s important to distinguish between the Diamond’s left and right sides, which are delineated by D1. The friendlier left side, also known as the Yellow Wall for its golden rock, hosts solid granite that’s vertical, crack ridden, and well-traveled, with most routes 5.10 to 5.12. The right side, meanwhile, looms gray and overhanging, with a reputation for loose, flakey rock and stout, techy free climbs from 5.12 to 5.14. With few full-length cracks, right-side free routes like Gambler’s Fallacy are not nearly as obvious; they’ve required first ascensionists to make multiple trips—ground-up by the earlier pioneers and, later, top-down—to free them.

By the end of the 1970s, most of the Diamond’s continuous cracks had been freed. Other than some vegetation and wetness, they were low-hanging fruit. Notably, it wasn’t until 1978 that the easiest free climb, the so-called Casual Route (IV 5.10a), was discovered. Right away it was free-soloed, first by Charlie Fowler (who accidentally dubbed the line when answering a query on how it felt: “casual”), then by Steve Monks. In Alpinist No 19, the Diamond free-climbing pioneer Roger Briggs wrote, “More than any other first ascent, the Casual Route transformed the Diamond. The once impossible and forbidden wall had become, for strong climbers on good-weather days, a relatively ‘casual’ outing.”

A Honeymoon of Sorts

One month later, in September 2020, I sit in the shade of a large tree in Eric Doub’s backyard in Boulder. Doub, 57, is a net-zero energy pioneer dedicated to accelerating society’s transition away from fossil fuels. He’s lived in Boulder, mostly, since 1970. “The honeymoon of 5.12 on the Diamond was due to be over, and I was going to do my part to make that happen,” he tells me, reminiscing about his Diamond years of the mid-1990s. “I knew a route would go there; I saw it up close; I put in the bolts in about the right places.”

In 1987, Doub and Briggs FA’ed Eroica (5.12b), between Yellow Wall and D1 on the left side. Eroica is stacked with hard, devious climbing, making it the Diamond’s most sustained 5.12. Doub, a keen, ultrafit go-getter, envisioned a much more difficult plumb line continuing straight up the blank-looking headwall where Eroica cut left. “I just knew there was something really special there,” he says.

Doub devoted the summers of 1993, 1994, and 1995 to forging the new line from the bottom up, alone and with various partners. Each day, he would push his highpoint, sometimes aiding crack-less faces via hook moves. Some days he climbed just 30 new feet before fixing his line and rapping. “I loved it up there,” he says. “It was a really important sanctuary, emotionally and spiritually.”

In summer 1996, Doub recruited Briggs, the most prolific Diamond free climber in history (think FFAs of Ariana [5.12a], King of Swords [5.12a], The Joker [5.12c] … ), for a complete ascent. Briggs, now retired, worked as a physics teacher and running coach at Fairview High School in Boulder. Tall and lean, he dances up the rock with impeccable footwork, in a way few climbers are able.

“We didn’t have any expectations of freeing it,” Doub says. Besides knowing how desperate the climbing would be, on the day of the ascent Doub was running on fumes. He had hosted a big party the night before and had only slept about 10 minutes, in his car, while waiting to carpool. Still, with Briggs in the lead, the pair unceremoniously freed 95 percent of the route to create The Honeymoon Is Over (5.12b A0).

Doub returned alone for a handful of days over the following two summers, top-down, trying to free the entire line. But he eventually became immersed in his business and family life. Moreover, he had been stricken by ankylosing spondylitis, an inflammatory disease that, over time, fuses vertebrae in the spine.

“By 2000, I recognized that I was no longer a climber I would invite up to the Diamond,” Doub says. He knew his route would go free, but that it would take a new breed of climber. “It’s going to require somebody who regularly climbs 5.14 at low altitude. That’s the baseline for even considering the route. In addition, mountain sense, reading weather, routefinding, gear-placing ability, traditional climbing, overall skills, superior fitness, and endurance—all of these things found a confluence in Tommy Caldwell.” In the spring of that year, Doub passed his topo to the most promising young climber in the country.

By summer 2001, the then-22-year-old Caldwell was on fire. He had been training rigorously, winning competitions, and bouldering V13 in Rocky Mountain National Park. “It was probably one of the strongest climbing periods of my life,” he says.

Caldwell studied Doub’s topo—he could hardly wait to try the many 5.12 and 5.13 pitches and the “not yet freed” sections. In June 2001 with his dad, Mike, in support, Caldwell onsighted the then first five pitches (some belays have since been moved) only to fall off the wet crux pitch, with its difficult, shallow corner and bolted boulder problem. He worked out the moves, then retreated.

“For a month and a half I thought about the climb,” wrote Caldwell in the 2002 American Alpine Journal. “I had not seen the entire route, but what I had climbed was everything Eric had said it would be.”

He returned in late July 2001 with Beth Rodden, his girlfriend at the time, supporting. With some wetness, “crunchy” footholds, and no chalk to follow, each pitch took him roughly 90 minutes to lead. “I was not acclimatized, and the whole day I was trying to get my heart rate down,” Caldwell says. “I [felt] so bad for Beth because she was hanging in her harness for so long.”

With cramping arms, Caldwell eked out the final pitch (5.12). “I hit the highest point of the Diamond just as my gas tank hit empty,” he wrote. His performance on The Honeymoon Is Over is still unmatched to this day: He sent on his second day, no falls, redpointing the crux, 5.13c pitch and onsighting the rest of the route, including 5.12 and 5.13 climbing up high.

No Joke on the Right Side

After Briggs and Doub freed Eroica in 1987, the rate of new free routes on the Diamond slowed. In the 13 years that followed, only two variations (D Minor 7 and Soma, both left-side 5.11s) and one new free route, The Joker, out right, were climbed—all in 1994 and with Briggs on the team. Aside from The Honeymoon, the future of Diamond free climbing would manifest mostly out right.

“The right side of the Diamond turns climbers back with more than letter grades—friable rock, creeping fatigue and motivational erosion from the altitude, the long hike, unpredictable weather,” wrote Jeff Achey in “Longs Strange Trip” in Climbing No. 145. “It’s not for everyone.” The Joker (5.12c) was the grand prize of the era, replacing Eroica as the Diamond’s hardest free route … that is, if you accept a significant “asterisk.”

Perfect style on long, hard free routes is more elusive than the media would have us believe. Climbers often describe any deviation from perfect—however that’s defined—as an asterisk. And a wall like the Diamond is littered with them, be they first ascents or repeats (e.g., the Dunn-Westbay Indirect, page 71, or Madaleine Sorkin’s repeat of The Honeymoon, page 74). The Joker is a prime example.

In 1993, Briggs was planning to free a new right-side route with Derek Hersey. But on May 28, Hersey fell to his death free-soloing in Yosemite. Steve Levin joined Briggs that summer, and they freed all but a few moves on The Joker’s final, 5.11+ pitch (the “Last Laugh”), using two points of aid on the soaked, overhanging offwidth. The following year, Briggs and Pat Adams climbed The Joker, named after Hersey, with an impressive no-falls performance from Adams. Only, he followed the crux, second pitch while Briggs, leading, fell off. “It’s a very unnerving pitch, something Derek would have loved,” Briggs says.

A few weeks later, the pair climbed through pitch three with no falls (Adams led the crux this time), but then veered right to explore new free terrain—and ultimately bailed. “I did finally go back and lead the second pitch without falls,” says Briggs. But again, he and Chip Chace didn’t finish The Joker. Rather, after three pitches, they made a tricky step left into King of Swords to produce a 5.12c linkup.

As for The Joker proper, the only other attempt I know of is when Josh Wharton bailed from the crux pitch citing loose rock and rattly fixed nuts. Says Briggs, “It’s possible that The Joker has never had a continuous free ascent.”

Full House

In 2001, Caldwell’s send of The Honeymoon shattered the title of the Diamond’s hardest free route by a full number. Also that year, Briggs and Topher Donahue freed what some call the wall’s best, most sustained 5.11: Bright Star (5.11d R), named in memory of Lauren Husted, killed in a fall in the Black Canyon in 1984, and the late Cameron Tague. Situated left of Eroica, seven of its eight pitches are 5.11, most upper end. It would be the last “first” on the Diamond for Briggs, then 50, who would eventually count 104 ascents of the Diamond.

Two years later, Donahue and Caldwell climbed five left-side routes in a single day, rapping to Broadway between each. Otherwise, no significant new climbs were reported until 2009, beginning with Phil Gruber and Brett Nelson on Full House (5.12b).

The Boulderites Cameron Tague and Kent McClannan had spent two days making the second ascent of the Kyle Copeland/Marc Hirt right-side climb Gear and Clothing (5.9 A4) in 1998, freeing what they could, including Tague’s onsight of pitch five’s spectacular 180-foot corner (5.11+). The two planned a return, but in summer 2000 Tague, 32, slipped off loose rock below the Yellow Wall and fell to his death.

Nine years passed before Gruber and Nelson patched together the line. After two days of rehearsal and prep work, including hand-drilling half a dozen bolts, both climbers freed the stunning line of steep cracks and corners that combined pitches of Gear and Clothing and La Dolce Vita (5.9 A4). A riff on the poker theme, the name Full House also refers to how Gruber, who, earlier this year at age 50 put up a multi-pitch 5.13+ on Mickey Mouse Wall near Eldorado Canyon, tries to squeeze every drop of productivity out of every day. For him, the challenge of climbing at a high level plus trying to be a good partner and parent make life feel like a “full house.”

A Cut Above

The following summer, in 2010, the Diamond gained another outstanding 5.12. And for the first time ever—for better or worse—the route was scoped, cleaned, and prepped entirely top-down.

Five years earlier, in 2005, Bruce Miller and I had tried to free the right-side route Enos Mills Wall (5.11 A3) ground-up, but we retreated in the face of loose, blank-looking rock atop the Winter Wall Dihedral (Layton Kor and Wayne Goss aided this corner on their FA of the Enos Mills Wall in 1967, which was also the Diamond’s first winter ascent). In 1980, Achey and Leonard Coyne had freed the corner at 5.11d—then the hardest free pitch on the Diamond—then bailed.

A quarter-century later, Bruce and I duplicated their attempt. At the time, we didn’t grasp how valuable our failure was. It offered us not only a close look out left, toward Jack of Diamonds (5.10c A4)—part of which would be integrated into our new 5.12—but also firsthand knowledge of unclimbed terrain higher and left that, 15 years later, would become the crux of Gambler’s Fallacy.

For us, ground-up tactics wouldn’t work on our 2010 project. Smooth, perhaps featureless rock would have mandated fruitless, time-consuming bolting forays that led into potential dead ends. So we started at the top. This meant a four-hour “approach” to the summit via the North Face (5.4–5.5), plus the hair-raising rappel, which we did six different days searching for a solid (and relatively dry) free route right of D1. More than once, storms chased us off before noon, leaving only a few hours of wall time. The climbing-to-walking ratio was demoralizing.

Nevertheless, we committed nine days over four weeks piecing together Enos Mills Wall to Jack of Diamonds with some new terrain in between. On August 26, 2010, Bruce and I freed Hearts and Arrows (5.12b), a clean, burly, well-protected line with just one 5.12 pitch that has become the most popular right-side route.

The Hardest and Highest

A few hundred feet farther right lies the Dunn-Westbay (5.8 A3), a single crack shooting straight to the top for most of its length, and an irresistible free-climbing challenge. Pete Takeda and Andy Donson, two local pioneers, worked sporadically to free the route for several years in the 2000s but found the plumb line too difficult. However, they did discover a sneaky leftward traverse on fingertip edges near the end of pitch three, avoiding the sustained, sequential crux above. They added two bolts to this crimpy boulder problem, which would define the Dunn-Westbay Indirect (5.13b), the Diamond’s second 5.13. Of note, the Indirect carries the distinction of being the only Diamond route that suffered a traffic jam during its first free ascent.

In July 2011, Takeda brought up Joe Mills, one of Colorado’s most accomplished climbers, to try the crux, which had stymied him and Donson. There, they were surprised to see fresh tick marks. “And then I saw someone coming up behind us super fast,” Mills says. “It ended up being Josh [Wharton].”

Wharton has few rivals when it comes to all-around climbing expertise. He seems as comfortable on Cerro Torre or Great Trango Tower as he is on scrappy, roadside 5.14 sport. His talent is overshadowed only by his dogged work ethic and thoughtful approach to training and improvement. Wharton had reached out to Takeda to ensure he wouldn’t be stepping on toes, but they never connected. “I just decided to go have a look,” Wharton says. He rappelled in, alone, on three different days, to rehearse the crux and decipher variations to the aid line higher up.

That July day, with Kevin Cochrane in support, Wharton arrived at the big ledge atop the Green Pillar. It was the first time he and Mills had met, and with both vying for the free ascent, their encounter proved awkward. They traded lead attempts on the 5.13 pitch, and on his third try that day, Mills sent it. Thrilled, he suggested he and Wharton finish the route together, despite his lack of preparation to top out. “I would have been really proud of putting up a cool new route on the Diamond,” said Mills. But Wharton, who hadn’t yet redpointed the pitch, wasn’t going to abandon Cochrane.

“Basically, I sent the crux pitch, lowered off, and went home,” said Mills. “I was pretty bitter about it at the time.”

Wharton redpointed the crux on his fourth try that day, knowing full well this could be his only chance for the integral FFA. “I carried on to the top, exhausted, and with wet conditions,” he says. “I managed to send each pitch but also took some falls, and yo-yoed a couple sections.” Unsatisfied with his several asterisks, Wharton returned two weeks later, with Jacob Fuerst belaying, and sent without falls.

Perhaps as important as the free ascent of the Dunn-Westbay Indirect was the light it cast on the elephant in the room: the original Dunn-Westbay. By 2013, the Front Range A-team of Caldwell, Wharton, Mills, and Jonathan Siegrist—America’s most accomplished sport climber—had all tried it on toprope and deemed it doable. But Caldwell didn’t just want doable; he wanted next-level. He visualized a rope-stretching pitch that eliminated the awkward chimney belay of the Indirect about 40 meters up the crux pitch.

“I was inspired by Yuji Hirayama’s ascent of the Salathé, where he did full ledge-to-ledge style,” says Caldwell. “I was like, why put up another 13c on the Diamond? There’s one already. If we can make it harder and make this epic 80-meter pitch, it will be an evolution.”

Caldwell and Siegrist woke on August 16, 2013, to a perfect warm, high-pressure day. But while they climbed the North Chimney to access Broadway, rockfall struck a roped climber below them, who then fell 50 feet, ending up unconscious and with many broken bones (ribs, skull, neck, back, and others). Right away, Caldwell and Siegrist abandoned their climb to help rescue the injured climber. It was Siegrist’s only chance that summer, as he was booked teaching clinics into September. The Direct would have to wait.

Later in August, Caldwell returned with Mills who, between grad school at the School of Mines and a PhD program in hydrology at the University of Colorado Boulder, had somehow found time to work the route, both solo and on lead with Dave Vuono.

From Broadway, Caldwell and Mills simul-climbed 300 feet of 5.10 to the belay ledge atop the Green Pillar, where the crux pitch begins. “Tommy had the first lead,” says Mills, “‘cause it’s Tommy.” Caldwell cruised the first 40 meters of 5.12, placing a handful of cams between fixed pieces. Just before the hardest section, at a good fingerlock and hand jam, he attached a Micro Traxion hauling pulley to his rope and clipped it to a piece. “As I climbed above that I would reach over and pull a handful of slack, then let go of it, and then do the next few moves. And then pull a handful of slack and let go of it,” Caldwell says. His creativity eliminated what would have been crushing rope drag on the 80-meter lead.

And it worked. He sent on his first attempt. Of the upper half, he said, “I climbed it with, like, two cams and 25 single biners,” explaining that Wharton had fixed many nuts.

Mills then followed it clean—his first time linking the full pitch. At 5.14b, the Dunn-Westbay Direct not only became the Diamond’s greatest challenge, but the world’s hardest route at that altitude. The few who have climbed it boast of its quality: the solid stone, purity of line, endless thin locks and laybacks, and the mental fortitude required. Wharton, who redpointed it in 2018, said of the crux pitch, “If you put it on the ground in an accessible spot, it would be world-famous.”

A Spiritual Place

The same day I redpointed Gambler’s Fallacy, Wharton and Gruber freed a variation to The Honeymoon that Wharton had accidentally discovered in 2015. “I basically just rapped the wrong way and Mini-Tracked up an unclimbed portion of the wall,” he says. “I instantly realized my ‘mistake’ would actually be an easier, high-quality version of The Honeymoon.”

Wharton, occupied with The Honeymoon proper (and always one to prefer a second ascent over a labor-heavy “first”), told Gruber about his discovery. In 2017 and 2018, then again in 2020, Gruber logged roughly 15 days on it, mostly alone. In 2018, he led every pitch free, but over two different days separated by two weeks. He wasn’t exactly satisfied, but he also wasn’t committed to returning.

Stating our asterisks is about more than just being honest. It’s also about setting the record straight: Without the gritty details, climbers won’t know where the bar has been set or how—or if—there’s room to improve on style. And as new free routes become harder to find, quashing asterisks is becoming more important than ever.

With Wharton’s encouragement, Gruber revisited the project. On August 9, 2020, he led the first three pitches, and Wharton the last five. Gruber fell once on the notorious “5.11c” pitch-four corner, re-led the pitch, then held on for the harder, upper half. “Somehow he just kept barely squeaking it out,” says Wharton, calling it “one of the better efforts I’ve ever witnessed.” That evening, the pair topped out Beethoven’s Honeymoon (5.13a), a clever deviation with little new terrain (about 80 feet) but that maintains the quality. “It’s a spiritual place,” says Gruber, of the Diamond. “It definitely demands my best, and so I feel like I rise to the occasion.”

Madaleine Sorkin: “A free ascent for myself”

In 2016, the Colorado pro climber and guide Madaleine Sorkin devoted two months to The Honeymoon Is Over (V 5.13c; photo above), a route more than a number grade harder than a woman had climbed on the Diamond. She rehearsed it on toprope for four or five days until she’d climbed it without falling. Then, she gave it two lead burns with Quinn Brett, who was also trying the route. “I’m fairly obsessed with big challenges and where they make me go psychologically,” Sorkin says.

On August 22, 2016, with Eli Nissan in support, Sorkin freed up to the penultimate pitch, a 5.13a. It was bitterly cold; she had heat packs taped to her ankles. A storm rolled in around 3 p.m., with rain and snow soaking the rock. The pair shivered at the belay for 90 minutes, then were forced to bail. Sorkin returned on August 30 but was stymied again by wet rock.

On September 7, Sorkin and Matt Owen left their Chasm Lake bivy at 5:15 a.m. Owen, jumaring for his first time ever, supported Sorkin’s ascent. Sorkin led the three 5.13 pitches as two, without falls. At the base of the second-to-last pitch, the 5.13a, Sorkin “got up to the last move and punted,” she said. “Like, the final move.” She lowered to the belay and tried again, but she fell a second time. “I was so pumped and tired. I couldn’t do it. So I went down to a no-hands rest halfway and was like, ‘Fuck it, I’m going from here.’”

Unsatisfied with her asterisk, Sorkin returned 10 months later, in 2017, to remember the moves. “I tried it once and decided it wasn’t in the cards,” she said. “I felt good enough about that to call it a free ascent for myself. And yes, I would like to have improved on the style.”

~~~~~~~~~~

The Gamble Paid Off

When Bruce and I first rapped what would become Gambler’s Fallacy in 2017, we were at once giddy with discovery—“Whoa, look at this finger crack out in the middle of nowhere!” Bruce said—and overwhelmed by the prospective difficulty. It took us several days to find the exact line, and even then it looked only remotely climbable. “Initially, I thought, ‘I’m never going to be able to do this,’” he says.

Over the days and weeks, it dawned on us that several sections might prove too hard for us. We honestly didn’t know. But this uncertainty eventually led us both to an important, if not liberating, realization: Even if we couldn’t climb the thing, the process of trying would be worth every moment. So, day after day, summer after summer, we racked up countless miles of hiking, hours of rehearsal, meticulous and troublesome cleaning (with the North Chimney directly below, loose rock either had to be tossed clear, to avoid smashing people, or, in the case of several large flakes, placed in a bag and hauled to the top).

Before dawn on August 22, 13 days after my ascent, Bruce and I rapped to Broadway from the Chasm View notch on a warm, cloudless morning. We had swapped roles—this time he’d lead everything while I jugged with a pack.

As you gaze upward from the top of the pitch-three offwidth, the complex geometry and blank appearance make Gambler’s Fallacy (5.13b) look all but unclimbable. The route goes up and into the wall before spending the next 300 overhanging feet climbing back out. This, plus the roof up high, is what makes it the Diamond’s steepest free climb.

At the stance atop the Winter Wall Dihedral, Bruce strapped on his kneepad and snugged his shoes. It would be his first time leading the crux pitch—or any of the hard pitches, for that matter. Up he went, around the corner onto the edge-riddled face. He climbed slowly, precisely, cruising the initial traverse. He fought hard, charged with energy, and lurched to Table Ledge.

By the time he sent the 5.12 crack on pitch seven, the wall had turned into a freezer. Cloaked in all his layers, Bruce shivered as the day’s output caught up with him. On the 5.13a Roof Pitch, he slipped off the roof itself—a rarity for him by now. Tired, but committed as ever, he tried again. This time he passed the roof and engaged the high crux, fighting, yelling, arms shaking. Moments later, a violent force yanked me upward; Bruce had fallen.

As he rested for a final attempt, something grabbed my eye off to the right: a body flying through the air, arms windmilling. A shot of adrenaline hit me. Then, the plummet began to arc and slow until the body swung like a pendulum in mid-air. It was John Ebers logging a 50-footer onto a No. 4 RP on the Dunn-Westbay Direct.

The next morning, after a bivy below Chasm View (13,300 feet), Bruce and I rapped in from the top so he could try the Roof Pitch again. This time he fired it first try. “It might have been one of those lowered-expectations kind of things,” he muses. On the last pitch, he skated off the 5.12d traverse, but lowered right away, pulled the rope, and sent. Bruce’s shouts of success echoed across the entire East Face cirque. His tenacity and optimism had paid off. “Just doing those pitches next to each other at a roadside crag would have been one of my best days ever,” he said.

Bruce, who was just eight days shy of 57 years old, was “awash with gratitude.”

To Be Continued …

John Ebers (24) and Ben Wilbur (25) very well may lead Diamond climbing toward the future. For the past two summers, they’ve quietly devoted themselves to the Diamond. With only weekends off, the engineers (Ebers, civil, and Wilbur, mechanical) certainly make the most of them. In 2020, they were on the Diamond every weekend but one from May 28, when the park reopened from COVID closures, through Labor Day. Their strategy? Snub the forecast.

“It didn’t matter what the weather said, we’d go up there,” says Wilbur. “The day I sent The Honeymoon (in 2020) it was raining and snowing everywhere, except one little pocket that happened to be the Diamond. We kept going until we were on top.”

They use a 100-meter rope so they can bail quickly. “Everything is bolted for 50-meter rappels,” says Ebers. “And, we have a Beal Escaper, so when storms come in we can do a 325-foot rap right to Broadway and then hop in that [bivy] cave.”

In August 2020, Ebers fulfilled his dream of sending the Dunn-Westbay Direct, a dream that started in 2017 when he first tried The Honeymoon Is Over.

As long and colorful as its free-climbing history has been, I believe the Diamond has an equally bright future. As Caldwell told me recently, “It’s cool that the Diamond has continued to reinvent itself for the new era.” New, hard free routes—on the right side, mainly—remain for the few willing to devote themselves to such a massive effort. But perhaps the most potential lies in raising the bar on existing routes: ground-up efforts, female firsts, single-day ascents, flashes, onsights, speed ascents, hard linkups, rope-solo free climbs—so much is up for grabs. These achievements will require a blend of styles, old and new: the boldness and vision of the early free climbers with the strength and tactics of today’s elite. All it will take is some imagination, some luck, and a whole lot of grit. They’re still out there. Lots of them … those diamonds in the rough.

Before Bruce and I descended from his redpoint of Gambler’s Fallacy, we trudged to the summit with an indescribable sense of fulfillment. I was deeply proud of him, and grateful for the many adventures we’ve shared since 2003.

Skinny and sunburned, with graying stubble and long hair, we dragged our tired, aching bodies back down the mountain. We couldn’t have been happier.

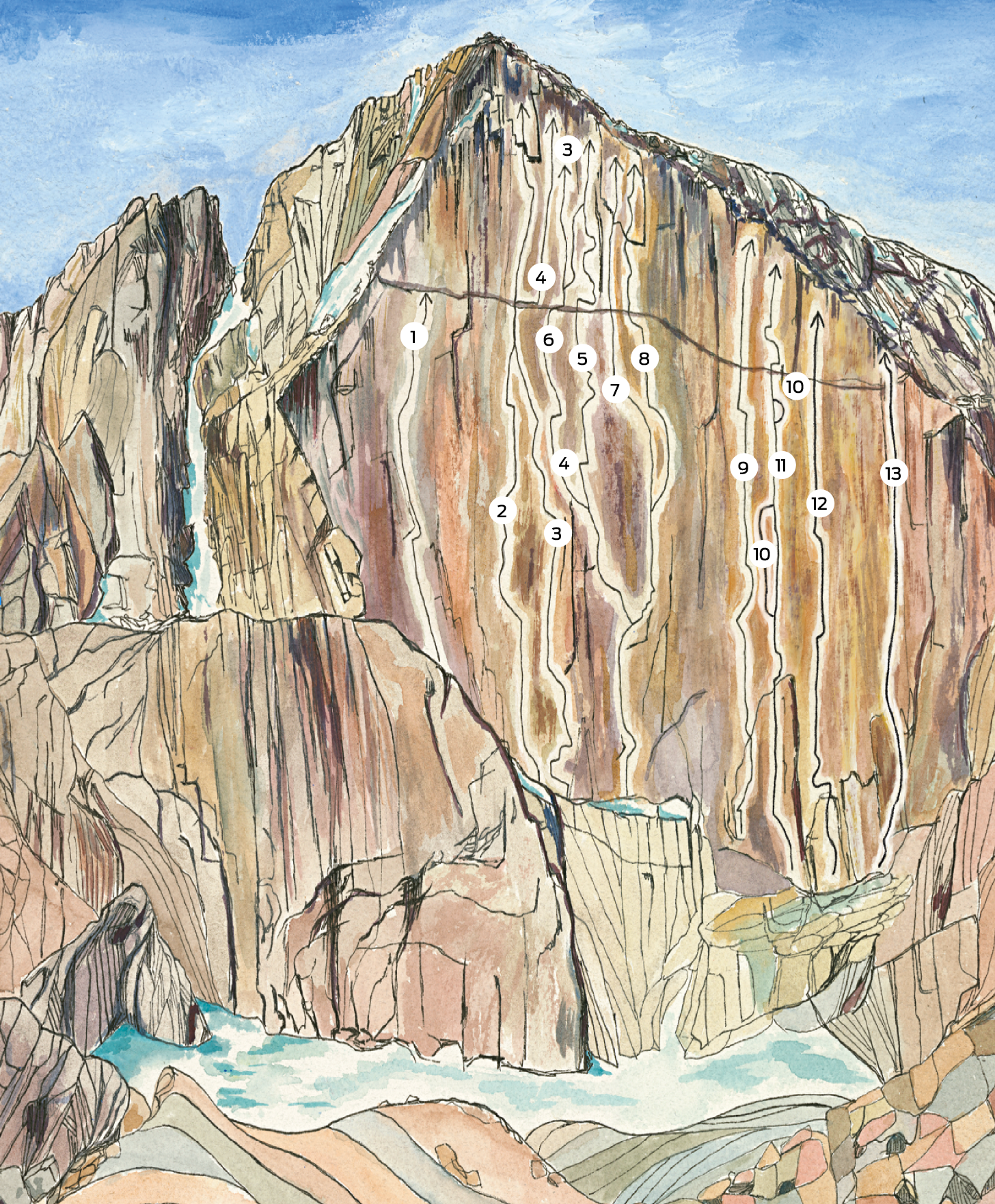

Diamond Free Climbs (1987 to present)

1. Stonehenge (aka The Wobbleisk)

(IV 5.12, 6 pitches)

FA: Topher Donahue, Kevin Cooper 2003

Donahue and Cooper quietly added this three-pitch 5.12 variation to The Obelisk, full of difficult cracks and corners. Pitch two involves hard moves protected by a No. 2 RP, and pitch four ascends a splitter on the right wall of the main Obelisk dihedral. Pitch breakdown: 5.8, 5.12, 5.11d, 5.12, 5.11b, 5.9

2. Bright Star (V 5.11d, 8 pitches)

FFA: Roger Briggs, Topher Donahue 2001

Pitch breakdown: 5.11d, 5.11d, 5.11b, 5.11c, 5.11d, 5.10a, 5.11d, 5.11b

3. Grand Traverse (V 5.11d, 7 pitches)

FFA: Ryan Montoya, Dylan Cousins 2019

Most pitches had been freed over the decades by different parties on various routes. In 2019, Montoya and Cousins rappelled in and cleaned a crack system just right of Eroica, finding solid rock, then returned the following day to free the route bottom to top. Pitch breakdown: 5.9, 5.11, 5.8, 5.8, 5.10-, 5.11d, 5.11-

4. Eroica (V 5.12b, 8 pitches)

FA: Roger Briggs, Eric Doub 1987

Pitch breakdown: 5.6, 5.9, 5.11b, “5.11c,” 5.11d, 5.12b, 5.11c, 5.10

5. The Honeymoon Is Over (V 5.13c, 8 pitches)

FFA: Tommy Caldwell 2001

Pitch breakdown: 5.6, 5.9, 5.11b, “5.11c,” 5.13c, 5.13b, 5.13a, 5.12b

6. Beethoven’s Honeymoon (V 5.13a, 9 pitches)

FA: Josh Wharton, Phil Gruber 2020

Pitch breakdown: 5.6, 5.9, 5.11b, “5.11c,” 5.11d, 5.12a, 5.13a, 5.12d, 5.12b

7. Hearts and Arrows (V 5.12b, 9 pitches)

FA: Bruce Miller, Chris Weidner 2010

Pitch breakdown: 5.6, 5.10a, 5.10a, 5.10c, 5.11c, 5.11a, 5.12b, 5.11b, 5.9

8. Gambler’s Fallacy (V 5.13b, 9 pitches; FA: Chris Weidner, Bruce Miller 2020) Pitch breakdown: 5.6, 5.10a, 5.10a, 5.11a, 5.11d, 5.13b, 5.12b, 5.13a, 5.12d

9. Full House (V 5.12b, 8 pitches; FFA: Phil Gruber, Brett Nelson 2009) Pitch breakdown: 5.9+, 5.10a, 5.12b, 5.11, 5.11+, 5.11+, 5.11, 5.11-

10. Dunn-Westbay Indirect

(V 5.13b, 7 pitches)

FFA: Josh Wharton 2011

Pitch breakdown: 5.7, 5.10c, 5.13b, 5.12c, 5.11d, 5.12b, 5.12b

11. Dunn-Westbay Direct (V 5.14b, 5 pitches)

FFA: Tommy Caldwell, Joe Mills 2013

Pitch breakdown: 5.7, 5.10c, 5.14b, 5.13a, 5.12b

12. The Joker

(V 5.12c, 6 pitches)

*FFA: Roger Briggs, Pat Adams 1994

Pitch breakdown: 5.10a, 5.12c, 5.11d, 5.12b, 5.12a, 5.11d (*not led free in one push)

13. Waterhole #3 (IV 5.11d, 5 pitches)

FFA: Jason Haas 2012

This steep, rotten obscurity is almost always wet. In late season 2011, however, Haas found the line drier than usual. Climbing ground-up, Haas “kept raining down rock on my partner, from small chips to dinner plates.” As Haas climbed higher, what appeared to be small cracks were mere shadows. Runout, wet, and cold, Haas bailed. In 2012, he returned to find it much wetter—its natural state. “I rapped over the line and started removing big choss blocks and monster wedges of moss,” he says. Undeterred, Haas redpointed the route at 5.11d, with Matt Clark supporting. Pitch breakdown: 5.10+, 5.11d, 5.11-, 5.10, 5.9

Chris Weidner is a journalist in Boulder, Colorado. A climber since 1988, he has authored more than 150 first ascents, from 5.14 sport routes in Colorado to 2,000-foot free routes in Canada.