Hayden Kennedy, On a Rare Ascent of The Ogre

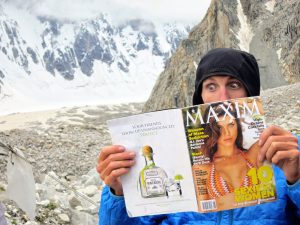

(Photo: Hayden Kennedy Collection)

Editor’s note 1: This feature was first published in Ascent 2013. Sadly, Kyle Dempster disappeared with Scott Adamson, while attempting an ascent of the Ogre 2 in Pakistan in 2016. The following year, Hayden Kennedy passed away after being caught in an avalanche with Inge Perkins in Montana.

Editor’s note 2: Just after sunset on July 13, 1977, Chris Bonington and Doug Scott topped out on the southwest face of Baintha Brakk (aka Ogre), a 23,900-foot granite and ice monolith in the Choktoi. They made their way down the summit slopes in the dark, then slung a rock frozen into the snow at the top of a steep, 150-foot wall. Scott rappelled first, angling sharply left and heading for a belay near the base. But as he reached to clip a piton, he stepped on a patch of water ice. His foot slipped and he swung wildly back right, smashing into A wall. In his classic story “A Crawl Down the Ogre,” Scott writes, “Glasses gone and every bone shaken. A quick examination revealed head and trunk OK, femurs and knees OK but—Oh! Oh!—my ankles cracked whenever I moved them.”

Over the next seven days Scott literally climbed down the Ogre on his knees. Delayed by storms, the team ran out of food, their feet and hands froze, Bonington rapped off the ends of his rope, broke his ribs and contracted pneumonia. At one point the climbers were reduced to digging up their trash and eating the dregs of boiled rice mixed with cigarette ash. But they never despaired, just kept working their way down, and through a rare combination of toughness and teamwork they all survived.

A year later, in 1978, Michael Kennedy, Jim Donini, George Lowe, and Jeff Lowe found themselves in a similar fix. High above the Choktoi glacier, within spitting distance of the Ogre, just shy of the summit of the unclimbed Latok 1 (23,442 feet), the team confronted a difficult decision. Jeff Lowe was sick and getting worse, but with only easy slopes separating the climbers from the top of one of the world’s hardest peaks, the choice to bail had to be weighed. After a quick conference they decided to forego the summit and get Jeff down.

Twenty attempts and 24 years passed before the Ogre was climbed again, and the north ridge of Latok 1 is still unclimbed. In the summer of 2012, Hayden Kennedy (Michael’s son), Kyle Dempster and Josh Wharton found themselves on the Choktoi glacier contemplating an ascent of Latok 1. Deterred by the objective hazards on Latok, they changed goals and set their sights on a first ascent of the South Face of the Ogre, and the third ascent of the mountain. But as Wharton battled altitude sickness, his condition deteriorating, Hayden found himself facing a situation eerily similar to his father’s conundrum on Latok, a choice that he had contemplated for as long as he had climbed mountains: With the summit in sight, would he leave a sick partner behind and climb on, or turn back?

Crunch, crunch, crunch. Our freshly sharpened crampons bit the ice like sharks’ teeth. We moved quickly across the icefall, knowing that once the sun hit the mountains, all hell would break loose. Josh Wharton and Kyle Dempster crested the final rise and raced off out of sight. I stopped to admire the Latok group and the Ogres, and remembered why I had traveled so far. I am not a spiritual person but these mountains have a powerful vibe. Avalanches roar in the distance, the wind bites cold, rock breaks, and ice shatters. These mountains are loud and alive. They don’t speak English or Urdu. To step into their presence is simply wild.

In the basin between the Ogre 2 and the Ogre 1 we established a safe camp for the rest of the day. The sun beat down on our tent as we all piled into the small space to escape the heat. I couldn’t sit still. My mind twisted and turned. I was the youngest at 22 and the least experienced. I found myself thinking about the coming days and tried to anticipate each moment. Dinnertime came slowly. Dehydrated pasta sat heavy in my stomach as I lounged in silence. This was Josh’s ninth trip to Pakistan. I wondered what was going on in his head. Was he nervous, too?

Sleep finally overcame my restless mind. Bizarre dreams of unknown worlds and fierce battles. Wind and snow raged through the high peaks as I floated high in the clouds. Blades of iron and steel crashed around me. The sound of Josh’s alarm jolted me awake.

It’s hard to get out of your sleeping bag when you’re looking into the darkness and know that you have nearly 11,000 feet of climbing ahead of you, but once our feet crossed the bergshrund we spanned a mental line where doubt became determination. At midnight we stepped off the safety of the glacier and into the unknown. The Ogre was in charge.

In 1977 the British alpinists Doug Scott and Chris Bonington climbed the Southwest Face of the Ogre, making the peak’s first ascent. The climb was one of the hardest of its era and to this day hasn’t seen a second ascent. Twenty attempts and 24 years later the Ogre was finally climbed a second time, and with just these two ascents, it is considered one of the world’s hardest summits.

When I was 13 years old, I read about Scott’s protracted nightmare in the anthology The Games Climbers Play. I remember my dad handing me that book as if it was the Bible. The stories between the book’s hard covers described a way of climbing that was almost mythical, unattainable to those who haven’t lived it. I read it cover to cover and I was left wondering: Will I ever experience the raw beauty of the mountains in the same way?

The sun rose over the Karakoram, warming our cold hands and feet and giving us perspective on the terrain we had already covered, as well as a glimpse of what was to come. We had soloed about 2,000 feet of low-angled snow with bands of moderate mixed climbing. Ahead, a rocky ridge looked like it would let us sneak by without breaking out the rope.

The climbing was easy, and being free from the encumbrances of ropes and gear felt brilliant. Our proposed route on the South Face of the Ogre started at the lowest point on the right side and trended left and up to the summit. The key was a rocky traverse at about 6,300 meters to gain more snow and ice. When we got to the traverse it didn’t look too bad, but despite my limited experience at altitude, I knew that the climbing would likely be harder and more nerve-wracking than expected.

I roped up and looked to my right. Thousands of feet below, the jumbled ice of the Choktoi glacier reminded me of the dreadful fall I could take if the Ogre decided to spit me off. Gear was a half-driven knifeblade in garbage rock. My head pounded and my limbs shook. I cannot fall, I told myself. I worked across the shattered stone, focusing on each step, each hand placement. I could barely hear Kyle’s and Josh’s shouts of encouragement.

Midway through the choss, I ripped off my gloves and committed to the final 100 feet. Complete exhaustion started to set in. I put in a tipped-out cam. This is it. At that moment the microwave-sized block I was standing on dislodged and tumbled down the wall. I caught myself as my shins slammed into the wall. Bleeding, resting my head on the rock, I thought, That was too close. A few more sketchy moves and I reached a solid crack with good granite. Anchors set, I slumped into my harness after two hours of terror. It’s hard to imagine that a 5.9 traverse could be so arduous and scary, but as I learned, the pitch of a lifetime is not always the hardest grade or on the finest rock.

Kyle took over and romped up easy snow and ice. Above us, the big wall loomed like Half Dome. Finally, we reached a flat bivy site and with no effort we had a perfect tent platform. Melting snow, changing out wet socks, eating, laughing and listening to the Rolling Stones, I wondered why I’d ever want to do anything else.

In the morning we packed our bags and started climbing. Silence. Dead calm. The weather was ideal. Nothing can stop us now. Plugging along with our heads down it was easy to ignore the beauty of the Karakoram. Kyle and I reached the top of a snow band and sat on a small rock outcrop. Josh, who had been moving slowly all day, had to rest every few steps and was coughing as he caught up with us.

“He’s just having an off morning,” Kyle said.

Kyle and I looked at each other and I think we both knew that Josh isn’t ever just “off.” Regardless, we pushed on—there was no reason to go down until there was a reason to go down. And even when there is a reason to go down, it is easier said than done.

Overhead, we saw the unreal golden buttress and the final obstacle to the summit of the Ogre. Kyle and I set off, swapping leads through bands of sometimes shattered brown choss and sometimes gorgeous white granite, usually with sparse gear.

We didn’t talk much, but knew that if we wanted to summit we needed to keep going. At about 3 p.m. clouds started to swirl above the summit, and the effort of punching through the waist-deep snow between the mixed pitches started to wear on us. Josh was fully worked, and it was apparent that we needed to stop. He groaned, coughed, and his thousand-yard stare said everything. Had we pushed too far?

I first hung out with Josh Wharton in Patagonia in 2009. He was already an alpine veteran and had climbed big routes in committing style all over the world. As a young, aspiring alpinist with zero experience, I looked up to Josh and felt like I had to prove myself. At the time we lived less than an hour apart in Colorado and climbed in nearby Rifle. In many ways that first year in Patagonia, I imagined myself as a young Josh Wharton. We bouldered and sport climbed together in El Chalten and our relationship quickly became the joking, shit-talking, Colorado-choss-hounding good-friends kind of vibe.

After Patagonia, Josh and I would sometimes go out for a day of bouldering and laughed as we struggled on the small holds. I started to call Josh “the Coach” because he was always figuring out how to be a better climber and help others do the same.

Josh and I never went alpine climbing together and joked that alpine climbing was silly and that bouldering was the true hardman’s sport. I kept climbing in the mountains and slowly started to get more mileage under my belt. But I always felt like I wasn’t up to Josh’s standards as an alpinist. I couldn’t put my finger on it but I felt like I was just a joke to him. This drove me to climb faster, take less gear and go bigger than I probably should have.

In the summer of 2011, after being in Pakistan’s Charakusa Valley for six weeks, I felt like I was starting my own chapter of Himalayan alpine climbing. On that expedition, my first, I met Kyle Dempster from Salt Lake City. Kyle is one of the strongest and most accomplished alpinists in America. Beyond his impressive tick list—FA of the East Face of Mount Edgar, FA of the North Face of Xuelian West, free ascent of the infamous Wall of Shadows on Mount Hunter—he has a unique attitude about climbing in the mountains. He doesn’t stress about gear, food, planning, conditions, weather, or potential pain—he just goes and gets shit done.

During Kyle’s and my time in the Charakusa Valley, I realized that while the mountains are your reason for being there, it is the people and culture that will have you coming back. Kyle in particular loves to travel, explore and get into the gritty lifestyle of the Third World. For him the journey into the mountains is just as important as climbing and I respect that philosophy.

After a near miss on the unclimbed East Face of K7 (22,749 feet) with our friend Urban Novak—a calm and competent powerhouse from Slovenia—Kyle and I returned to the U.S. with a plan already in mind for the summer of 2012. K7 seemed like a reasonable objective that we could polish off quickly, allowing us to use our time in the Charakusa to acclimatize for a bigger objective. In early July 2012, the three of us spent 30 days in the valley and promptly got our asses kicked on K7. We managed to reach the summit, but it certainly wasn’t as easy as we had expected. After K7, Urban went back to his Ph.D. studies while Kyle and I rested before our trek into the infamous Choktoi Glacier.

While we’d been in the Charakusa, Josh and the Bozeman hard-man Nate Opp had made their own voyage to the Choktoi to attempt the Northwest Face of Latok 1. It was Josh’s fourth trip to the mountain, and he had told me that it would probably be his last. In previous years, conditions and weather had never granted him a chance to give Latok a good try. Once they reached the Choktoi, however, Nate concluded that he wasn’t psyched on Latok and headed back to the U.S. Josh immediately asked if he could join our team. Resting in Skardu after K7, Kyle and I prepared our minds for a stab at Latok 1.

The Choktoi has been a part of my life since I was a little kid playing in the dirt at the crag with my parents, Julie and Michael Kennedy. In 1978 my dad, George Lowe, Jeff Lowe and Jim Donini tried the North Ridge of Latok 1. They fought for 26 days and came the closest of anyone to climbing that incredible mountain from the north, a monumental effort. Photos from the route are burned into my memory, and my first look at the real thing made me almost lightheaded as I thought about their truly incredible and terrifying effort through storms and sickness. My generation will never fully appreciate what those guys did. Today most expeditions constantly update their progress with blogs, Twitter and other social media. To me, this is bogus, a distraction that takes away from the experience that is meant only for you and your partners. Yet in the small world of modern expedition climbing, which brings with it media and sponsorship pressures, you have to make an effort to climb offline.

When Kyle and I started the four-day trek into the Choktoi Glacier, it felt like the real adventure of the summer was about to begin. As I hiked in I thought of my dad and his friends on this same approach. Did they know what they were about to get into? Did we know what we were about to get into? The mystery inherent in climbing mountains always makes me think critically about my decisions and motivations. Can we ever begin to understand the drive to climb? We never know what is going to happen on a big alpine route, and if we did, would it even be worth it?

Climbing Latok 1 had been Josh’s dream for years, but it didn’t turn out to be ours. After arriving in base camp and getting a closer look, Kyle and I agreed that the proposed route was too risky. A large serac threatened the first third of the Northwest Face, and the potential terrain traps above the serac also scared us. Talking about our concerns with Josh was difficult, and I knew that he didn’t agree with our assessment. Josh seemed to have turned Latok 1 into an obsession. The objective hazards didn’t bother him—or maybe he felt the risk was worth it.

We briefly considered the North Ridge. It is objectively safe, technically moderate and remains the classic unclimbed line in the Choktoi. Yet as motivated as we were by the route’s history and aesthetics, none of us wanted to deal with its long sections of horizontal ridge climbing. Josh had found deep, unconsolidated snow and impassable double cornices on his previous attempts, and we saw nothing to indicate that this year would be any different.

For Kyle and me, the primary objective from the beginning had been the North Face of the Ogre 2. It might prove too hard, but the idea of getting shut down by a difficult section inspired us. This type of adventure would give us a glimpse into the future of technical alpine routes in the Karakoram. It was the kind of mountain that wakes you up at night.

We all felt the tension between our two different mindsets and worked together to agree on an objective. The unclimbed South Face of the Ogre 1 was our compromise.

August 20, 2012 – 6,900 meters,

South Face of the Ogre

We chopped at a steep ice slope for nearly four hours trying to carve a bivy spot. Finally we’d made barely enough space to set up our tent, the right side hanging over the void. The only noise came from the stove. Josh lay motionless in his sleeping bag, his face swollen from edema. Mashed potatoes, beef jerky and water made him feel a bit better. He talked about his symptoms and his concern for climbing higher.

I kept thinking about my dad on the North Ridge of Latok 1 in 1978 in a very similar position. Jeff Lowe was sick from days on the mountain and had a fever complicated by the altitude. Dad, George Lowe and Donini sat in a small snow cave discussing their options. They had spent over 20 days on the ridge and were about 1,000 feet from the summit when they decided to turn around and get Jeff off the mountain. Kyle, Josh and I were a similar distance from the summit of the Ogre. What had my dad been thinking? What should we do? These questions raced through my mind and kept me awake all night.

“When you make a choice in the mountains, you have to understand it fully and be ready for any of the outcomes,” Dad always told me. “Once you make the choice, there is no going back. You must commit.”

In reality, early the next morning, our choice to keep climbing and leave Josh behind in the tent was not very difficult.

“I know how hard it is to climb on this glacier. The chances of sending here are so slim,” Josh told us. “You guys are ready for the summit. I don’t want to be the one to turn you around.”

Kyle and I roped up as soon as the words came out of his mouth. If it had been anyone else, we would have already been rappelling. We committed to the choice, but I am not sure if we were fully ready for the consequences.

We packed light and left Josh with the stove, food, sleeping bags and extra gear. Kyle and I tied in, ready for the summit push. This had been our plan from the beginning, the “Pakistani Double-Header.” The rock was impeccable and each pitch had some of the best climbing either of us had ever done in the mountains. Steep M6 and ice smears on good granite became our reality. As we crested the summit ridge, the clouds below swirled around the surrounding peaks.

At about 7,100 meters we reached a ridge that culminated at the summit snow slopes. I was fading; my head felt heavy. It was our third day on the Ogre and, counting all the traversing, we had covered close to 4,000 feet per day. My feet and shins were battered from the endless front pointing. Wearily, I looked up at the final 500 feet of mixed ground and waist-deep snow.

“I can do this!” Kyle yelled into the wind. It hurt too much even to look up as I simul-climbed behind.

Wham! A piece of ice the size of a loaf of bread tumbled down the steep snow and hit me square in the chest. I almost fell backward and dragged Kyle off. My eyes watered from the pain. I couldn’t breathe and my head pounded.

We reached the summit of the Ogre as the clouds scattered. The views of the Karakoram are vivid in my mind today. Kyle and I hugged and laughed. What a summer it had been! Yet only half the battle had been won.

I unzipped the tent to find Josh curled up in a ball. He lay motionless in the heap of sleeping bags.

“Dude, it’s time to go down.”

Josh opened his eyes and I saw the doubt in his face. He didn’t say a word as he sat up and laced his boots, moving like a slug. Finally we were packed and started rappelling. We threaded Josh’s belay device, clipped him into the anchors, and watched him every second. He dozed off at the belays and mumbled to himself. Darkness engulfed the Ogre, turning the rappels into an endless nightmare. A small rock buttress was our only option for a bivy. Kyle and I chopped into the stone and frozen mud for hours trying to make a tent site, and crawled into the nylon prison.

The next day was consumed by rappels. Coil ropes, pull ropes, get ropes stuck, get ropes unstuck. When we reached the glacier, it felt like a huge weight had been lifted. We were finally safe.

On the Ogre, Josh came too close to the edge. I try and go back into my thought processes and review everything that happened. So many variables led to the morning in the tent when Kyle and I left Josh. I get lost in the what-ifs and should-haves. Josh has been one of the most important mentors in my life and to see him suffer so hard haunts me.

The fact that Josh had only been to 6,000 meters once that whole summer and still decided to charge with us raises its own set of questions. Was he relying on his brute strength to get him through? Was it acceptable for Kyle and me to let Josh climb with us, knowing his acclimating process that summer? Did the tension of our disagreements about Latok allow our egos to get in the way? Were Kyle and I blinded by summit fever? I don’t know.

Maybe the time will come when I will understand our choices and whether we did the right thing, or maybe that time won’t come. The mountains bring us to our knees and force us to crawl. With glory, success and summits, our egos can overwhelm our judgment. Through doubt, failure and hardship, our egos invariably get checked back to reality. The Ogre is in charge.

This article appeared in ASCENT 2013 (Rock and Ice issue 2010).

More on Hayden Kennedy

Remembering Hayden Kennedy

Climbing World Mourns the Loss of Hayden Kennedy and Inge Perkins

Hayden Kennedy: Superballistic

Deep North: A Trip to the Arrigetch Peaks

First Light: Hayden Kennedy and Jesse Huey Prepare for an Alpine Battle