Yosemite Legend John Long Recounts The First Free Ascent of Astroman

“Watch me close,” I said to Ron remembering my first time on this pitch, several years before. “This might get funky.”

I felt anxious, amazed, primed— everything all at once. El Capitan in a day was a done thing. In traditional-style rock climbing, free-climbing a genuine big wall remained the last and greatest prize.

We wanted to be first and here was our chance to close the deal, 11 pitches up the overhanging East Face of Washington Column. From the start I’d warned the boys that this last pitch might shut us down, so we were bursting at the seams from the suspense of battling all the way up here and still not knowing.

“Get us off this thing,” said Ron.

He was only a kid. Seventeen, I think. I outweighed him by 60 pounds, but Ron had caught me many times so I didn’t question his hip belay. John reached an arm from a patch of shade, passed me a couple slings and said, “You’re the man.”

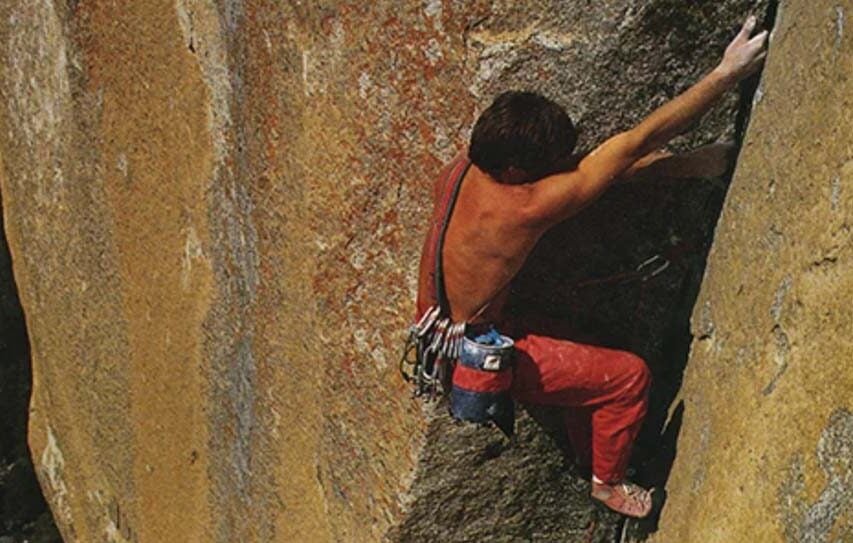

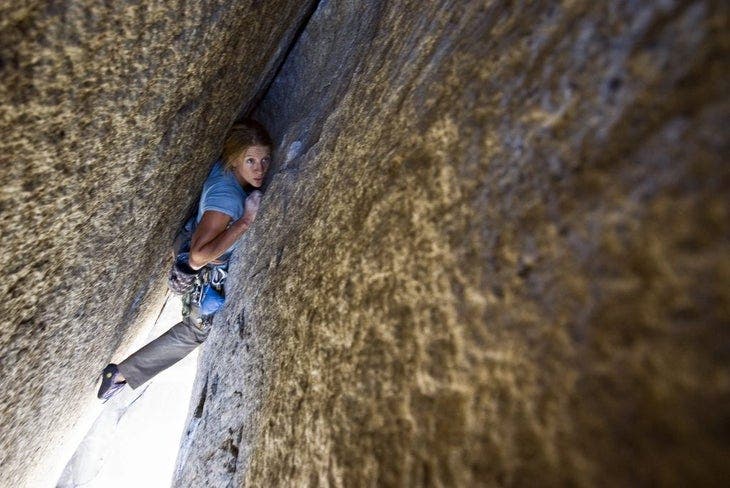

That helped. All the way up we’d cheered and prodded one another as aid pitch after aid pitch fell to our free-climbing efforts, pitches that soon became classics: The Boulder Problem Pitch, with its fingertip liebacking and scrabbling feet; the Enduro Corner, a soaring dihedral that goes from thin hands to big fingers, right to the belay bolts; the ghastly Harding Slot, a bottomless flare that in coming decades would dash the hopes of so many Europeans; and the flawless Changing Corners, a vertical shrine of shifting rock planes with a continent of air below. For over a thousand feet now, the blond/orange cracks kept connecting in remarkable ways, and we kept busting out every technique we knew. Never before had we experienced a route so continuously difficult. To our knowledge, no climbers ever had.

Fifty Feet to Go

My toes curled painfully inside my EBs but I reached down and cranked the laces anyhow. Sweat dripped off my face onto the rock. We passed around the last of our water as I racked a few small pitons and several Stoppers and Hexcentrics on the sling around my shoulder. I slowly chalked up, glanced over at John and said, “I’ll take some tunes, if you please.”

John reached into his day pack and punched the button on our little cassette deck. Jimi Hendrix’s “Astro Man,” our theme song for the route, blared through the top flap. John flashed that insolent grin of his and said, “Rock and roll, hombre.”

John Bachar. He looked more like a math geek than an athlete, with his elfin build, stringy blond mop and two silver buck teeth. Back in high school, I’d get midnight calls from John about his new climbs or boulder problems, meaning I immediately had to beg a car or even hitchhike to wherever so I could bag these routes as well. Meanwhile John began his lonely quest to become the world’s greatest solo rock climber, a ritual he practiced for an astonishing 35 more years before it finally took him out on July 5, 2009. But then, smirking on that ledge, he was 18 years old, and looked about 12.

I took a last sip of water and shuffled out on the tapering ledge, around a corner and over to moderate liebacking up the left side of the short pillar, ending at a 25-foot headwall. All the way up, the rock had been diamond hard, but here it turned to choss. Three summers before, on my first big wall, I’d nailed this last bit via rickety pins bashed into a rotten seam. All through the previous night I’d wondered how we might free-climb the seam; one glance confirmed we never would. However, just right of the seam and straight up off the pillar, the vertical face bristled with sandy dimples and thin, scabby sidepulls. I’d have to toe off pure grain, and yank straight out on these scabs, praying they didn’t bust off. The only protection was several tied-off baby angles slugged into that seam. While organizing our gear I’d talked big about not bringing a bolt kit and about high adventure, cha cha cha. What an ass. I couldn’t hang my hat on those pins. The only nut was in the lieback crack, 10 feet below. It was one of those surreal fixes where I was plainly screwed yet somehow had to make do.

I reached up and grabbed the first sidepull. It felt world class just to hoist my feet off the pinnacle and I stood sulking for several minutes. Here was the chance of a lifetime and I was too gripped to commit. Maybe Ron should have a go? He would race up this, I thought. Ron was the most gifted climber we had ever seen. He’d hiked the Endurance Corner in nothing flat. Same with the Harding Slot. Nothing could stop him. But I couldn’t give him this one.

Ron first turned up in Yosemite when he was 14 and it was like Sitting Bull returning to Standing Rock: the chief had finally come home. The elements were living things in him, and the rock and even the Valley itself seemed fashioned just for Ron. In some nameless way, fundamental as wind and chain lightning, Ron Kauk was father to us all. Not long after that afternoon on the Column, Ron would spread his wampum across Europe, hurling it at the Karakoram and beyond, closing the circle on the traditional era of climbing. But I couldn’t call him now.

Too anxious to sleep, turning this last pitch over in my mind like a pig on a spit, I’d fairly dragged Ron and John out of their sleeping bags, then had burgled the two leads up to this crumbly face. Now I couldn’t muster the sack to pull a single move.

I hated this situation. I loved it, too. Not a soul, not even God, stood between me and the decision I faced. Do or fly. The moment my feet left that pillar, my life would change forever. Gritting my teeth and fingering those useless pitons, I peered up at the flaky holds, shifting foot to foot on my tiny stance. It felt like the route was taunting me, playing my ego off itself so I’d lose patience, crank into something stupid and plummet terribly as the whole Valley howled.

But fuck it. There were holds, and I only had 25 feet to go. Maybe less. I glanced left and growled, “Here goes.” Then I blanked my mind and pulled off the pinnacle.

After a body length I knew I could never reverse a single move, so I accepted that I was basically soloing. Strangely, I relaxed. If this is what the route demanded, I’d just go with it. The climbing felt like 5.11, scared as I was of snapping an edge, doing screwball twisty moves to keep some weight over the granular footholds.

After about 10 feet I stretched high off a flexing carbuncle and pinched the bottom of a big grimy tongue drooping down, clasping both sides in turn, anxiously wiggling a few sketchy wired nuts into the flaring grain. The only pins that would fit behind tongue were bashed into that seam below.

Fifteen Feet to Go

Bear-hugging up at mid-5.10, I gunned for the roof, feet bicycling the choss. Grain rained down. The tongue flexed and groaned. My eyes zeroed in on the short hand crack extending down from the roof, but after a few more bear hugs I reached a sloping sand bar. Unfortunately, I’d have to straight mantel to stretch a hand into the crack. This was bullshit. If I blew off here I was going for a monster whipper and probably hitting the ledge. I hated this route with all my heart. Piece of shit god-damn garbage wall from hell! What the fuck?

“What’s going on over there?” Ron yelled from around the corner.

“Just watch me,” I yelled back.

“We can’t even see you,” said Bacher.

“Just watch the damn rope,” I said.

I splayed my feet, soles flush on the crud, one hand pawing the tongue as I raked the sandy berm, trying to get down to solid rock. Cocking into a mantel at last, I pressed it out like molasses, gingerly placing a foot on the crunchy veneer and stepping up with my teeth chattering and no hand holds. Finally I could stretch up to the crack, sink a hand jam and slot a bomber hex.

I leaned back off the jam and gazed down at the pitiful wires festooned from the tongue and the loose face, patted with chalk marks, plunging to the tied-off pegs. This was like the best pitch I’d ever done. Perfect, really. And beneath the pinnacle, diving 1,200 undercut feet straight into the talus—a face of wonders. I felt like the Valley’s favorite son. Reaching out over the roof I could just clasp a good, flat-top hold. I pulled up and realized my hands were on the top of Washington Column.

We called it Astroman. Following an early ascent, the British ace Pete Livesey called it “the world’s greatest free climb,” a title that stuck for the next 15 years. During that time the last pitch, “the sting in the tail,” cleaned up nicely following a thorough brushing and hundreds of ascents. Several long thin pitons were welded behind the tongue, as well as some copper- heads. But the caveat for the last pitch remains the same as it did in July 1975: Don’t fall.

This article appeared in Ascent 2011.