Climbing Has Meaning, Until You Confront Death

Pico Cão Grande, 1,200 feet of jungle limestone on the island of São Tomé in the Gulf of Guinea, off Africa’s west central coast. The remote tower went from being of little interest to climbers to seeing multiple attempts and ascents in recent years. (Photo: Jacob Kupferman)

The most fucked-up part about brain cancer is that you keep hearing how much it changes people: It makes them mean. Nurses tell you which medicine is for your dad’s agitation, but deflect on what that actually means. “You’ll know,” they say.

You freeze up inside when you realize the only thing scarier than the person you love living long enough to lose themselves is if they don’t. As desirable outcomes begin to collapse in on themselves, you’re eventually only left with the haunted hope that the person will either wake up new or not at all.

But morning after morning you wake up the same, waiting to learn which awful way this ends, until finally you realize you’ve been bunkered down, blood in your teeth, witness to the waning hours of the wrong war. Live or die, no one really fights cancer. My father certainly didn’t. That’s a bumper sticker, not an actual thing. Cancer takes what it wants. The real fight, the one I’ll always remember, is not if you live, but how you live once you know you won’t.

“The jungle must be indifferent to our preferred level of risk tolerance,” I said to my friend Mike Swartz as we trudged through the canopy’s hot underbelly, scanning for snakes. Mike, Sam Daulton, Remy Franklin, Jacob Kupferman, and I were hiking toward basecamp through São Tomé’s moist broadleaf forest. It was August on the Equator, and we were all drenched in either sweat or rain.

São Tomé is the larger of two islands in the Gulf of Guinea, and together form Africa’s second-smallest, and possibly least-visited country: São Tomé and Príncipe. A single winding road—EN n° 2—traces the perimeter of the island, but doesn’t quite connect. From its southern flank, if you look north, past the tessellated palm plantations into the Parque National Obo, you can see Pico Cão Grande, a 1,200-foot volcanic plug exploding into the cloud-soaked sky. At the base of the primeval black fang is a massive cavity, bleached-white above a leafy sea. In 2016, Gareth “Gaz” Leah and Sergio “Tiny” Almada established a stunning climb through this 15-story cave and up the southern face of the tower, but they never sent the crux. Two years later, we were there to try.

Up ahead, Sam and Remy swung their machetes like two drunk clowns. Hiding in the branches, the birds mocked them in discordant symphony. Fat beads of water percolated through the understory, and visions of venomous cobras seeped out beneath the shadows, flooding my anxious mind. As the sun slipped behind the clouds, the dense canopy bent the remaining light to nearly nothing, sliding the forest into a fever dream.

Back in the city of São Tomé—everywhere we went in São Tomé was called São Tomé—our local liaison, Diego, had assured us that rubber boots, dull machetes, and a little vigilance were a viable alternative to the antivenom we couldn’t afford for all the snakes we kept hearing about. Unconvinced, I imagined the serpents, from their vantage point in the trees, laughing at our nerve.

“Maybe we should have splurged on that antivenom,” I said to no one in particular.

We continued in silence, up a sharp ridgeline stitched to the sky with vines thicker than the trunks they strangled. Camp wasn’t more than a few miles from the palm plantation where we’d parked, but the hike was steep and muddy. Just as my feet began to blister, the forest parted and revealed the decaying core of a dead volcano. Up close, Pico Cão Grande looked like an exorcism in retrograde motion, rejected from the earth, caught in the mist, and slowly crumbling back to dust. I held my breath against a fragile faith that whatever was waiting up there was worth it.

Diego assured us that rubber boots, dull machetes, and a little vigilance were a viable alternative to the antivenom we couldn’t afford for all the snakes we kept hearing about.

In December 2015, 18 months before the doctors found a massive glioblastoma in my father’s head, I’d met Mike tucked onto the trunk of a small palm tree, far above the valley floor in El Potrero Chico. Alden Sonnenfeldt and I had caught up with him and his partner, Remy, after the 12th pitch of Time Wave Zero. They were waiting for Sam and Seth Cohen above them. Sam was an impressive climber, but the same couldn’t be said for his rope management—this was his first multi-pitch. After a long, slow slog up the Mexican classic, the six of us agreed to get dinner that night.

Almost everyone else knew each other already from college in the Northeast. I’d grown up surfing in San Diego, but moved to Boston in 2013 to start a Ph.D. in oceanography at MIT. In between, I’d drifted from a decent youth gymnast to a really bad JV wide receiver and a shit-faced frat boy to a decent graduate student. I grew up with enough privilege to follow my heart, but my heart’s never been much of a leader. With the opportunity to do anything, I’ve never felt it possible to choose the right thing. So I’ve floated mostly, never quite sure how to optimize a life.

Over the years, I grew closer to Mike, Sam and Remy, and began to let climbing consume me. Here, I hoped, might finally be the right thing. Annual winter trips bridged our drifting geography, and in 2016, most of the crew returned to Mexico. (I was on a research vessel in the Southern Ocean.) After a week in El Salto, they met Gaz Leah for a drink near Monterrey. He told them about an almost-mythical spire ripping through a tiny African island. São Tomé and Príncipe had been colonized by Portuguese slave traders 500 years ago, but new growth has reclaimed many of the old plantations, and the country—74 percent rainforest—is known today mostly for its remarkable biodiversity. Historically, Pico Cão Grande was seldom thought of as something anyone might try to climb.

Gaz explained how he and his team had bolted a rain-soaked route up the spire. They called it Nubivagant, Portuguese for “Wandering in the Clouds.” After three weeks of 14-hour days to equip the climb, they ran out of time to free the three crux pitches through the cave. Gaz suspected the second might be as hard as 5.14a, and he didn’t make the other 14 pitches of wet, hot, heavily vegetated choss sound casual, either.

“Plus, the spiders,” Gaz claimed, “are the size of your head, and the trees are filled with snakes.” Even if he’d been embellishing, the island’s nearly 200 inches of annual rainfall and 80-degree mean temperature were easy enough to confirm. It wasn’t surprising that fewer people had been to the summit of Pico Cão Grande than had been to the moon—and not one had done it free.

Yet, in the dusty light of a Mexican saloon, my new friends began to nurture a crazy idea about this distant peak no one seemed able to climb: Maybe they could.

Within the sparse architecture of Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center, just north of San Diego, there is space for your mind to drift to places you aren’t exactly comfortable with. Afraid of something, or maybe everything, I wandered the bright hallways of its in-patient treatment facility and tried to train my mind on anything other than my father’s condition. It was April 2018, nine months after my mom had called me in Boston to say they couldn’t remove the brain tumor I didn’t know he had. Now, my father’s intermittent hospital visits had dissolved into an indefinite one.

The doctors called him James, but most people knew him as Jim. My dad had worked as a civilian scientist at SPAWAR—San Diego’s naval research laboratory—for most of his career before bootstrapping a local movement to improve K–12 STEM education across the city. Over the last decade, he had leveraged SPAWAR’s meager outreach infrastructure and injected it with unimaginable enthusiasm. My dad would bounce between inner-city classrooms like a benevolent carnie, with a bag full of magic and a bit of physics to expose it, collecting an endless troup of protégés. I’m not even sure if they were his students, or even students at all, but every Thanksgiving I would return to updates on his army of disciples and their various accolades. I could hardly keep track of their names.

My father was kind that way, sometimes egregiously so. He spent his life laying out everything to anyone he found, but right now he was just lying down; folded into the empty geometry of a tiny hospital bed, as if his body had been borrowed from the margins of a lesser Picasso sketch, somewhere beyond the conceivable edge of home.

Late one night in spring 2018, almost a year after my dad was diagnosed, I got a call from Mike. I was half asleep back home and almost didn’t answer. I was tired of trying to allocate the appropriate amount of reassurance to my well-intentioned friends, who kept checking in. The truth was, I didn’t know how I was doing because I couldn’t tell the difference between the tough parts and the numb ones. All these inquiries did was make me uncomfortable with how much time I spent thinking about how I should be feeling instead of actually feeling those things.

That wasn’t why he’d called, though. Mike wanted to know if I’d come to São Tomé. He pitched the trip, eagerly reporting that his friend Jacob was on board to photograph and a rope company might even toss in a cord or two. However, when he reminded me that the goal was freeing a 15-pitch, possibly 5.14 snake-infested chosspile, I promptly declared, “I can’t even send 5.13 in optimal conditions. If I wanted to not-send a hard sport route, I could go to Rumney.” Then, lying in bed, missing my friends, I clarified, “But I’ll think about it.”

Over the next week, as my father’s condition deteriorated, I let myself hide in the shade of distraction. It was nice to imagine something bright beyond a bleak horizon, but the trip was two months away, and agreeing to go meant conceding my dad would be gone by then. As soon as I caught myself entertaining the idea, I felt ashamed for not being torn apart more completely. So, instead of trying to reckon with that, I just kept Googling “São Tomé + snakes.”

My research revealed that the island’s most venomous snake was the cobra-preta. Ecologists originally mistook it for a forest cobra introduced by early Portuguese farmers to control the pest population, but couldn’t explain why someone would recruit one of Africa’s deadliest snakes to hunt rats. However, new genetic research has resolved that this snake is, in fact, a unique species. The single peer-reviewed study to date suggests the cobra-preta could grow up to 10 feet long and thicker than a human arm. Toxicology data is mostly anecdotal, but involves stories about plantation workers jumping from trees, exploding eyeballs, and phrases like “man bitten-man lost.”

Unsettling as this was, I managed to extrapolate that if São Tomé could codify me as a real climber, then maybe I could find my footing as a serious person. I wasn’t sure if that math checked out, but all of a sudden I didn’t care.

A week later, I picked up the phone and told Mike I would go. I wanted to feel brave without feeling broken. I wanted to feel better.

After a couple of drinks, I messaged the Pous on Instagram. Their response was almost all emojis: three snakes, two bombs, some flames, and an invitation to meet for coffee on the island.

Before the radiation, my father kept a wild head of unkempt hair with long, smooth waves that framed a thick pair of glasses. Now, without it, he looked more like Walter White than Albert Einstein, though he was still the archetypal absent-minded professor, the kind of person who knew his way around a textbook better than the grocery store. Once, when I was a freshman in high school, he invited an entire dinner party into a dark bathroom to show them how the Pacific Ocean, caught in a bottle, could glow at red tide. While packing my lunch the next day, he forgot which bottle had seawater in it. I found out in third period, a moment too late.

My dad had a rich history of forgetting things like that, but my mother—Maya—fell in love with the innocent way that apathy escaped him. The way he cared. My father tried his best to teach me—their only child—the same; to be brave enough to believe that hard work was worth it. I could tell that he wished there was a better metric than grades to make sure I was trying. After college, I remember how sad he looked when I bragged about easily passing an entry-level engineering licensing exam despite walking out halfway through.

My dad didn’t demand a thing, but he couldn’t hide his quiet disappointment when I didn’t check my work.

The five of us met up in a beer-sign-lit Portuguese hostel halfway to São Tomé. Over dinner. We discussed the disconcerting news that a Spanish team, led by the brothers Iker and Eneko Pou, was already there, their goal unknown. After a couple of drinks, I messaged the Pous on Instagram. Their response was almost all emojis: three snakes, two bombs, some flames, and an invitation to meet for coffee on the island. Upon our arrival, they confirmed that the tower was falling apart and filled with snakes, and they had the footage to prove it. Worse, their team had already freed the damn thing—twice. Nubivagant now went at 5.13c/d, plus they had established another line, Leve Leve, that took a more difficult path out the cave.

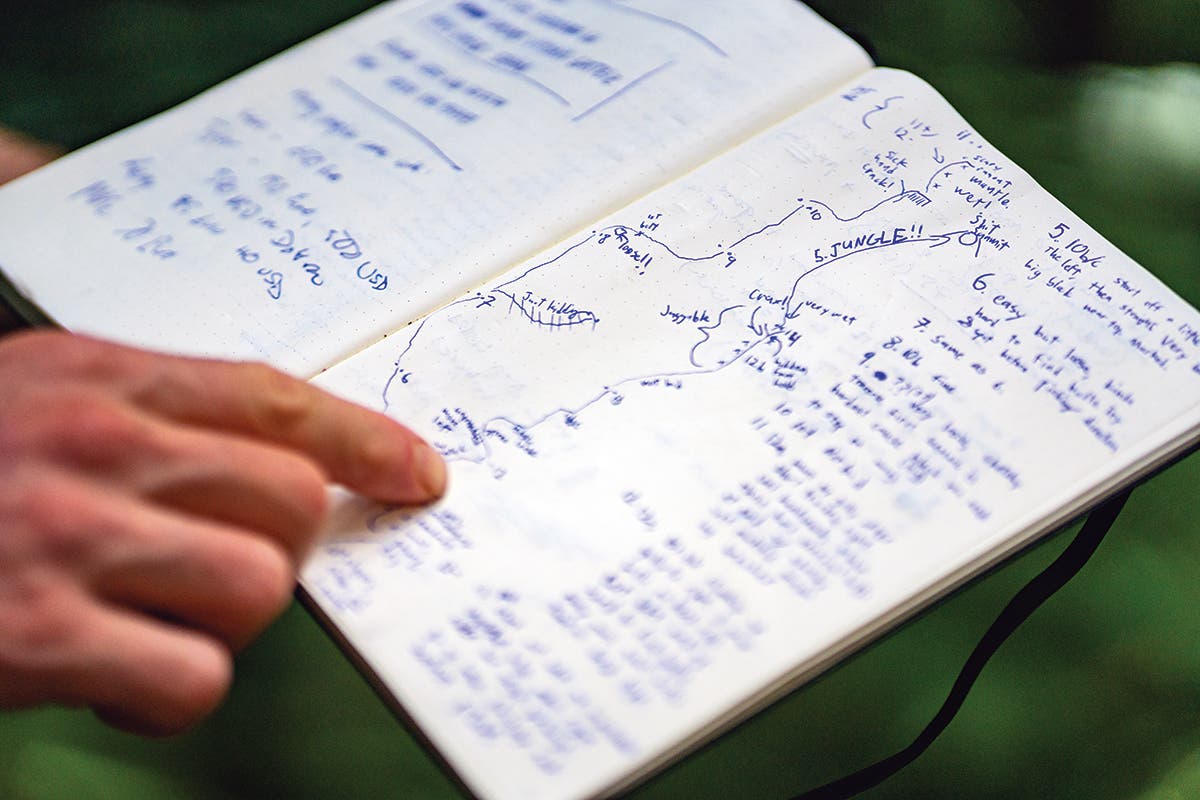

We also learned about a third climb supposedly established that summer by two Swiss climbers, that avoided the cave. The Pous only met them in passing, on the hike in, and didn’t remember the route’s name, but thought it might summit at “ten”—which we assumed meant 5.10. Eager to consummate rumors of an easier line, Mike and I set out to find this mysterious route on our first day of climbing. We hugged the base of the spire, bushwhacking through thick ferns and aimlessly looking up until we spotted a line of dirty bolts peeking out from the broken face.

The first hold I touched was soaked. The next one exploded. I’d placed a purple C4 from the ground to keep Mike and me above a steep hill, and, moments later, as we hung below the jug that had just disintegrated, I was glad I had. I pulled back on, dug my fingers into the mud, and threw my heel up into the vacuum the explosion had created. With my foot wedged in a root system, I clipped the first bolt and immediately screamed, “TAKE!” I pulled on every draw and still couldn’t finish the pitch, which evidently ended somewhere beyond a small waterfall. Mike tried and failed, too. Eventually, we sulked back to camp beneath a building rain.

When it rains in the jungle, the invasion is comprehensive. Individual droplets ionize in the branches and approach you in three dimensions. Then, the swollen sky begins to pulse with the static silence that happens when water, coming down in sheets, refracts through the trees.

Camp, at least, was mostly sheltered by the cave, but with so much moisture in the air, nothing got dry in the traditional sense. Parasitic tumba flies reportedly like to lay their eggs on hung laundry, so Mike and I threw our wet jackets into the gear tent. Exhausted, we settled down beneath our flaccid mosquito net and watched Sam’s and Remy’s headlamps twinkle overhead. Night was falling, but they were still suspended somewhere near the top of the cave. We yelled up to them, but their voices, or ours, were lost in the screech of insects.

Their goal that day had been to sort out the first four pitches of Nubivagant. Based on the roar of trundled rocks Mike and I had heard throughout the day, it didn’t appear to be going well for them. Starving, we cut up some vegetables that had already begun to rot and wondered what the fuck we were doing there. Sam and Remy’s chance at an FFA was gone, and Mike and I couldn’t even climb the kiddie route.

After dinner, I crawled into my sleeping bag and looked out beyond my tent. Through the fog, I could see the full shape of the moon. The way its light reflected the water made me think this was all an acid test, but I couldn’t figure out what for. Then, outside, I heard Mike call his family and couldn’t help but feel like the rest of the team had a disproportionate number of living fathers.

While Mike talked to his father, I thought about mine.

It doesn’t matter how clean you keep a hospital—you can’t bleach out bad news. I can still smell the sterile rot of the well-kept lobby where we waited when my mother got the call from the specialist in Baltimore. He had been remotely monitoring my father’s progress in one of those clinical trials reserved for lost causes. “The aggressive expansion of the tumor is not responding,” he probably told my mom, with the frankness that a pending death demands. I’m not sure—I couldn’t hear. But I could see how the topography of her cheeks changed, how they sank somehow.

Upon our arrival, they confirmed that the tower was falling apart and filled with snakes, and they had the footage to prove it.

In the cold air outside my father’s hospital room, we made the impossible decision to bring him into hospice care. We wrestled with how to tell him, but as we stumbled through the fog of a slow war with the hospital bureaucracy to discharge a dying man, I learned that death didn’t scare him. He was only afraid we might think he was giving up, ashamed he had agreed to abandon us. I know that because he told me.

The day we took him home, I got there first to stage a carload of medical equipment. Everything had guardrails, wheels, and the crisp, sad smell of a new car you can’t afford. When I was done, I thought the living room might buckle under the weight of it all.

Before my mother arrived, I rushed to rearrange the plants and toss around some blankets to conceal the true intention of the space. It looked sloppy, but the effort mattered more than the aesthetic. Slowly, the three of us settled into this new life, trapped in the slow churn of dead-time. Occasionally, friends or hospice workers came by, but mostly it was just us. I think my father liked that. He tried to explain once, in hopeful gasps, “The aperture keeps getting smaller, but the focus stays the same.”

Water was everywhere, saturating the soil, cascading down the rock, and hanging still across the sky, but the type you could drink was an hour away, and we ran out every other day.

The next morning, I volunteered to walk to the river with Remy, making myself useful after the prior day’s debacle. Remy was chipper for a guy who’d spent 12 hours hanging on a rope prying loose rocks off a route that, somehow, got sent a week earlier. He didn’t seem to mind; he almost seemed excited as he described how good the climbing looked beneath the cave’s mangled, moldy carapace.

By the time we returned, Sam was up on the second pitch, giving it hell. Pitch two, the crux, packed a tough boulder problem before giving way to 50 feet of sustained 5.12+ technical face, balancing between the scales of a petrified dinosaur. Mike, meanwhile, belaying from a portaledge, was launching skyward each time Sam got spit out by one of two vicious dynos right off the deck.

“You’re trying pretty hard for that second ascent, eh?” I chirped in a half-ironic sort of way.

“Pues,” Sam said in Spanish, with a long drawl and slight smile that almost concealed his disappointment.

Remy and I set the water down, and then reminded some rats that the potato sack was off limits. Our compromise, negotiated in good faith, permitted the rodents to pass through camp freely provided they stayed out of the food.

I racked up and met Mike below the first pitch of Nubivagant. The rock looked crusty and fragile, but felt solid. It was nothing like the forgotten biology experiment we’d tried the day before, steaming with ooze. We both sent on our second go.

The next day, Sam and Remy kept working the tough stuff, inching closer by the burn. With newfound optimism, I tried the first pitch of Leve Leve, 130 feet of 5.12d with eight bolts and a good amount of gear. It began just right of Nubivagant and continued out directly over camp. After a burly splitter, a couple of hard, thin moves gave way to a jagged dihedral that looked like the jawline of a handsome skeleton. The rock was exfoliating, and I whimpered the whole way up, but I was happy to fight, even if I took at every bolt. I left my gear in, committed to trying again.

Remy was chipper for a guy who’d spent 12 hours hanging on a rope prying loose rocks off a route that, somehow, got sent a week earlier.

As I touched the ground, Mike let me know that a concerning number of the insect colonies I’d cleaned off the pitch had blown straight into our produce. I assured him that the maggots would bring out the mildew flavor in our beans. We grinned, then started to cook dinner and plot our summit push. The plan was to send the scouts: Mike and I would jug past the cave, leaving time to climb the rest. That way, the A-Team—Sam and Remy—would be armed with whatever beta we could supply.

I kept waiting for my father to get mean, mining the minutiae of moments for an inflection point. I wanted to see when it happened, as if I could correlate observation and absolution. Once, I played him a Frank Ocean cover of “Moon River,” and he abruptly contended that he preferred the Audrey Hepburn original. Another time, he reciprocated a hug with the blunt assertion that I stank. But a conversation about my pretentious music taste or poor hygiene was pretty on-brand for us. My dad never got mean.

Instead, he cast a gentle smile against my fears, and refused to give traction to the end of things to come. Every morning, he insisted I guide, or wheel, or carry him over to a table where his computer waited for him to polish off one final paper. He could hardly see, but he sat and typed, as slowly as someone could. This manuscript wasn’t his magnum opus or really anything of consequence at all. Yet, letter by letter, thought by thought, he pecked away until gravity did what gravity does. Once he had slouched beyond reach of the keyboard, I would bring him back to bed, where he waited until he had the strength to type again.

It’s frustrating to watch someone die like this, but it’s also inspiring. Even deep in the trenches, with a head full of tumors and sheets soaked in urine, my father kept it together. He kept laughing, kept teaching, kept loving, and most spectacularly, kept himself.

Around 3:30 a.m., I began to ascend the fixed lines below the dull glow of a few stars spit across the morning sky. The weather was warm, with a light, wet wind. I continued up quietly in the dark, until I reached the lip of the cave just before the sun. Mike was already there, flaking our ropes, ready to begin.

Above the roof, space opened and collapsed all at once, like waking up underwater. A pregnant mist, animated by early light, painted the world a queasy gray. The rock was bone black, sharp and porous like coral from an ancient sea. Dark vines and stubborn trees leaked from its pores, and frail cracks traced the acceleration of geological time. Looking up, I thought I was a diver, low on oxygen and frightened of the bends.

The angle relaxed as the route meandered, traversing through a blocky maze. No move was harder than 5.10 for six pitches, yet every one threatened to dislodge an angry block. So we tiptoed like nervous dancers, afraid to weight a single hold.

Near the top, three of the final pitches broke into brief sections of steeper rock. Pitch 12, the best above the cave, revealed a 35-foot headwall, soaked and short but miraculously solid. The small, wet crimps felt enormous beneath the full force of my fingers. I was nearly relaxed by the time I reached deep into a jug and recoiled with infant-like fear as something slithered across my hand. I’d been so scared of rockfall, I’d forgotten about the snakes. I then realized what it was: “Just a lizard. A harmless fucking lizard,” I shouted down.

The rock mutated into what our crowdsourced topo described as Pitch 15: 5.JUNGLE. I gave Mike one last wide-eyed, Bambi look, pulled off the belay onto a tangled ramp of creaking roots, then took off through the muffled trellis of trees and dirt. My pace quickened as I grew comfortable in the branches, weaving between their arms for protection, until I wasn’t even climbing anymore. I was on all fours, racing uphill with fresh energy, through the diminishing light toward a break in the trees. In my stupor, I tripped and tumbled into a small clearing. I got up slowly, exhausted again, and looked around. This must be the summit, I thought, and started to pull up slack.

I wanted the mist to break. I wanted the clouds to unfurl, like a carpet kicked down a long hallway in heaven, with my dad at the end. I closed my eyes and imagined the most incredible scene, but on the other side of the daydream there wasn’t even a view. Just a trampled patch of weeds below a low sky obscured by trees.

I forget if it was a phone or a cup or something else entirely, but whatever my mother threw at me successfully severed my attention from my headphones. I lowered them over my furled brow, confused by the aerial assault, and turned from my makeshift office in the dining room to hear her yelling from my father’s side: “He’s ready, he’s leaving. Get over here before he’s gone,” she sobbed, angry at me and the rest of the known universe. We had had a false start a few days before, but this time wasn’t a drill.

Last time, during the trial run, there’d been time. There was time for me to loop through his favorite songs and tidy up loose ends. For two hours, we listened to the smooth ukulele on “Over the Rainbow” fossilize into perfect sincerity, until the lady from hospice drove over and told us my dad wasn’t dying yet.

This time there was no music; there was no time. My mother and I each held one of his hands, laid our heads on his chest, and listened to his heart stop. The feeling was indescribable, but it had to do with wanting. Like you never had the words. Like all of a sudden you can see the end of understanding and feel the rising crest of fear.

It kind of takes your breath away.

On the way home, as we were flying north over Ghana, the feeling finally calcified. In the shadow of my father’s ghost, I could feel the shape of mine. I’d spent the majority of my adult life wading through this uncertain space between who I was and who I wanted to be. If I swam hard enough, I always thought I could catch a current to carry me across; but I remembered then, on the hazy night my father died, how I had dipped my finger below the surface and felt the water was still.

Before São Tomé, I thought the mountains could save me. Or at least convince me I wasn’t a coward. I thought I could emerge from this minor adventure lit up with the calm satisfaction of a Life Well-Lived. In the end, on paper, it had all gone according to plan. We had clear skies for most of the second week, Sam and Remy sent every pitch of Nubivagant, I sent the first pitch of Leve Leve, and Mike and I were the first Americans to summit, which, in a certain, careful light is kind of cool, I guess. We didn’t even see a single snake.

If you squint hard enough, climbing can feel spiritual, but it’s easy to forget that spirituality is not actually reality. In church, as in the mountains, there’s always the promise of a happy ending, something to fight for, a safe harbor somewhere just beyond the summit. It doesn’t matter if salvation is in the hands of God or back at basecamp 1,200 feet below. Courage comes easily when you know what you’re up against and can see clear through to the other side. In real life, things are not so well-defined. Most people have no idea what they’re fighting for. Not as they sift through shards of broken glass looking for a reflection of who they really are, and not as they toss through the night, overflowing with cancer, waiting to die, trying to muster the grace to say goodbye.

In the long, hot summer of 2018, I learned that life is not like the mountains. People like to conflate the two, but I don’t buy it anymore. It feels good to know where to go, but eventually you’re right back where you started, relieved and alive, but without a clue about how you might be of use. If in those moments you feel a queer nostalgia for when you could articulate what you were afraid of and when you knew what you were fighting for, you may start to wonder what it means to be brave for something else.

If you squint hard enough, climbing can feel spiritual, but it’s easy to forget that spirituality is not actually reality.

A few months after São Tomé, my mom called me in tears. She’d been fighting a nameless employee from San Diego’s Department of Health and Human Services to correct my father’s occupation in the public record. He studied fluid mechanics. Inexplicably, the best they could do on his death certificate was “Fluid Machine.”

James Rohr: A Devoted Husband, Loving Father, Gracious Teacher, and Fluid Machine.

It’s not wrong. We are, after all, a mostly watery collection of mechanical parts. But it’s not ideal, either.

Some of the time, though, or probably most of it, communication with the dead comes through strange channels. Metaphysically speaking, transmission lines aren’t always reliable, but after half a lifetime of civil service, of course my father still believed in local government. So as far as feedback from the grave filtered through the cogs of the county bureaucracy is concerned, Fluid Machine isn’t bad.

Two years later, I’m still looking for north. I finished my doctorate, did a stint in government work at the U.S. Department of Energy, and left during the austral summer of 2020 for a postdoc in Tasmania. I landed in Hobart a week before COVID-19 made its way down to the southern edge of the earth.

Before the island locked down, I went to a crag called the Boneyard, two hours northeast of Hobart in the Fingal Valley. The cliff perches on a small, sloping ledge 500 feet up Bare Rock and is littered with little piles of broken bird bones. Below, the scattered patches of discolored eucalyptus, charred from last summer’s fires, reminded me of fall in New Hampshire, and we climbed until the lactic-acid levees burst.

At night, 20 or so climbers gathered around a thunderous fire and swapped stories over sore arms and spilt wine. The grizzled Tassies who had developed half the island’s climbing were there, and thought this was the most crowded the crag had ever been. They weren’t upset, though; they were just excited for the community. It was the type of moment that makes the world feel small.

Then, on the drive home, scrolling through the news on my phone, I could feel the joy start to slip away. Suddenly, the whole world was staring straight down the barrel of a story without a happy ending. With isolation orders inevitable, I wondered if we could all be brave enough to do nothing at all. Now, as I write this, alone in a new country, thinking about all the friends I haven’t met yet, I miss the mountains more than ever.

Climbing doesn’t make my life meaningful—I’m not scared to admit that anymore. But climbing might not be meaningless, either—not if it helps. The mountains are more like medicine than anything else; they don’t make you whole, but they can hold you together. For a while, under their weight, the pressure can squeeze every vague little fear you have beneath the surface of a more immediate one.

That has to be worth something, too. When the river is vast and the tide is slack, a compass isn’t as important as the mechanisms that keep us afloat. Besides, what’s more courageous than the stubborn, stupid hope that in time you might learn to feel better?

Pico Cão Grande

Pico Cão Grande stands 2,175 feet above sea level, and 1,214 feet above the surrounding jungle on the southern tip of the São Tomé. The basaltic pillar formed when an old volcano eroded around its hardened magma core. Climbing on the Pico began in the 1970s.

1975: First ascent (5.ladder).

A Portuguese–São Toméan team of Jorge Marques Trabulo, Constantino Bragança and Cosme Pires de Santos tackled the spire using any means necessary, including aluminum ladders.

1991: Japanese Route (5.10 A2; 400m; 18 pitches). Naotoshi Agata, Kenichi Moriyama and Yosuke Takahashi established an 18-pitch route up the southeast face.

2014: Asturian Route (Unfinished).

The Asturian/Spanish climbers Hector Fernandez González and Victor Sánchez Martinez attempted a new aid line on the east face, but left it unfinished.

A recent revival has seen at least two free routes established, with a handful of attempts to repeat them.

2016: Nubivigant (5.13c/d; 455m; 15 pitches).

FA: Gareth “Gaz” Leah, of the U.K., went to Sao Tome with a team consisting of Sergio “Tiny” Almada of Mexico, and the Americans Kathy Karlo and photographer Matthew Parent. The team fully equipped the line despite a litany of challenges, but were left with only four days to clean and send, ultimately leaving the crux second (5.13c/d), third (5.13a), and fourth (5.12d/13a) pitches unsent. Leah says that though the route is “equipped as a sport line, this is anything but.”

The route was again attempted by the Catalonians Toti Valés and Miquel Mas in 2017. They summited but did not send the crux.

FFA: After establishing Leve Leve (see below), the Basque brothers Iker and Eneko Pou, along with Manu Ponce, sent Nubivigant in team-redpoint style over two days of good weather. Based on what we witnessed a week later, we were shocked and impressed by the state they sent it in, as the jungle had quickly reclaimed the route since 2016.

2018: Mysterious Swiss Route (Not 5.10!).

We can confirm that at least one pitch exists, which likely goes free at a grade much harder than 5.10. After that, we cannot say.

2018: Leve Leve (5.14a; 450m; 13 pitches).

FA/FFA: Iker and Eneko Pou, along with Manu Ponce and photographer Jordi Canyi, established this climb right next to Nubivagant as part of their 4 Elements project. After the crux third pitch (5.14a) in the cave, the route continues in mostly traditional style, with many pitches cleaned to accommodate gear. It joins Nubivagant for the upper two and a half pitches.

American climbers Sasha DiGiulian, Angela Vanwiemeersch, and photographer Savannah Cummins attempted a second ascent in 2019; however, they were befuddled by rain and ultimately summited via Nubivagant, but did not send.

Tyler Rohr spent most of his climbing days on the East Coast. He now works for the Australian Antarctic Partnership Program in Hobart, Tasmania, where he researches oceanography and climate change.