Mystery, Adventure, and Julia: North Carolina’s “Tradical” Quartzite

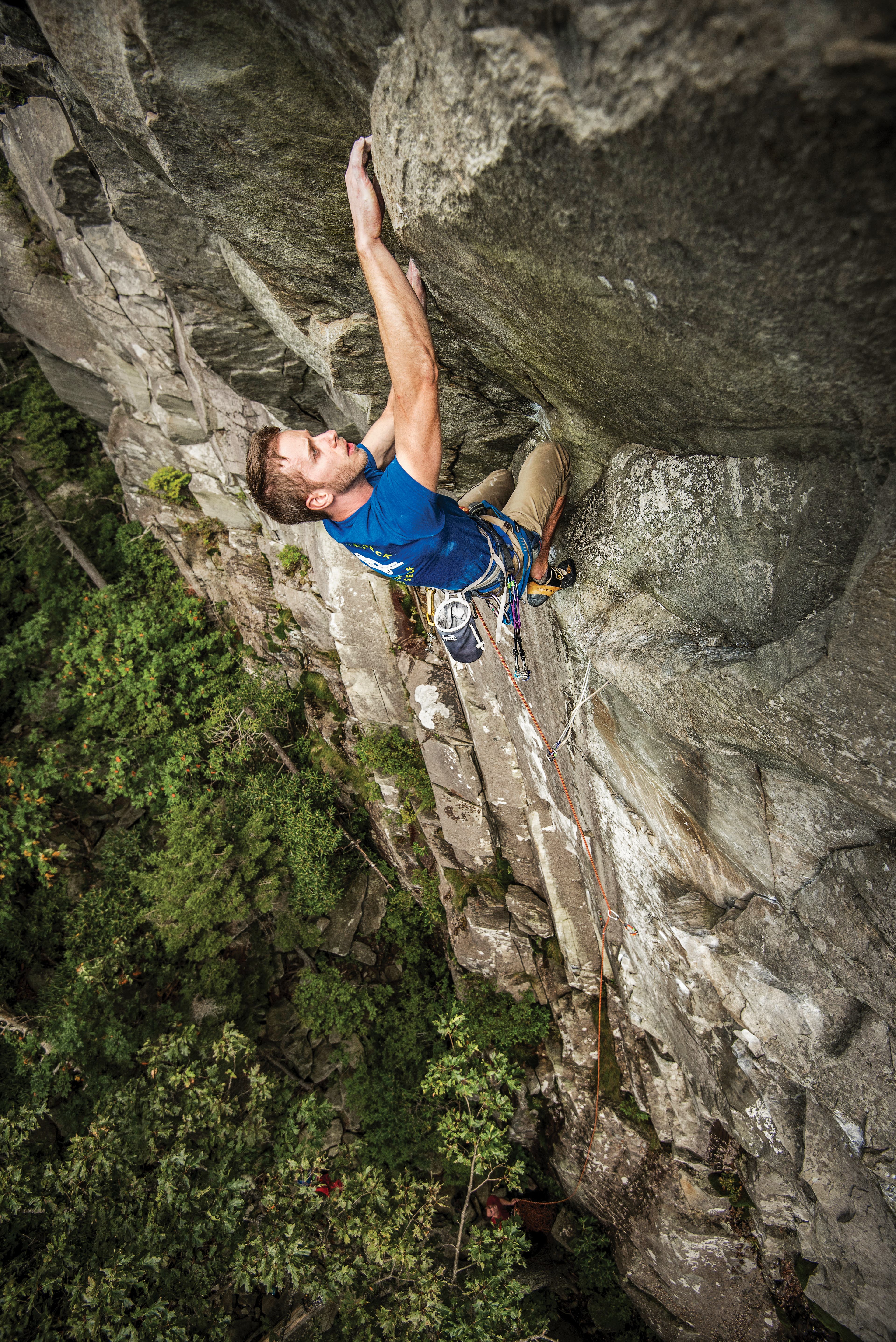

"Bryan Miller" (Photo: Bryan Miller)

“Why am I doing this?” I wonder, rubbing my eyes. Alone in the kitchen at 4:18 a.m., I wipe up peanut butter as I make my sandwich for the day. Mentally, I am not ready to pad up the void well above gear on North Carolina’s overhanging quartzite, nor for the physical beat-down the steep, vegetated approaches provide. Nonetheless, I wrap the sandwich in foil, slide it into the brain of my pack, shoulder the load, and head out my door to meet Lee Champion, my longtime climbing partner, for another Southern “alpine” start.

Today, we are bound for Julia, a three-pitch 5.10b on Shortoff Mountain inside the Linville Gorge Wilderness. Linville, two hours from our home in Charlotte, cuts a jagged gash into the western NC mountain carpet, revealing a concentration of flinty quartzite, a metamorphic rock characterized by horizontal bands, irregular cracks, large roofs, cryptic gear, and steep face climbing. We have walked by Julia for several years, intrigued and excited, yet intimidated by the overhanging fingertips corner crux and stories of climbers thwarted by the steep opening pitch.

Outside my home, the predawn air feels thick, moist, and windless, conditions NC climbers know well. Headlights approach, so it must be 4:30 a.m.: Lee is never late. As we drive, raindrops hit the windshield. “Dude, is the dew point as bad as I think today?” I ask Lee. For Southeast locals, this obscure meteorological measurement is an obsession. Heat and humidity are easy to manage, but the dew point—that ephemeral moment when water vapor transforms back into liquid, rendering the rock surface more slip-n-slide than climbing medium—is not.

Two hours later, our muddy car parked at the end of the Wolf Pit dirt road, we reach the trailhead for Shortoff Mountain, the southern terminus of the Linville Gorge. From here, the trail grinds up to the eastern gorge rim along steep, knee-cracking switchbacks through a canopy marred by multiple wildfires. Soon, the rain gives way to a softly illuminated landscape, revealing the Blue Ridge Mountains all around. Time and moisture have shaped these mountains into less dramatic peaks than those found out West, forming an undulating landscape more human in scale. On the grey lichen-covered cliffs that poke through the hills, routes ascend hundreds of feet yet somehow remain part of the forest, forming a canopy that traps moisture and dapples light sufficiently to propagate yet another, even thicker ground layer of rhododendron and laurel—beloved by nature photographers yet dreaded by climbers.

Due to a unique geology of ancient ocean beds, fault lines, and continental collision—better known as the Appalachian Orogeny—high-quality quartzite crags saturate North Carolina. The geologic phenomenon results in glassy, exposed, bullet-hard rock of interlocked crystalline structure. Standout areas include Moore’s Wall, a 200-foot crag in the flat, central part of the state. Moore’s boasts around 150 adventurous, sandbagged routes from 5.5 to 5.13, including classics such as Zoo View (5.7+), with a big horizontal roof; Air Show (5.8+); Quaker State (5.11a); and Filet-o-Fish (5.12a), a burly affair named in honor of Tim Fisher, the “Mayor of Moore’s” and a prolific local first ascensionist known for his staunch ground-up ethics. And Ship Rock, two hours northwest of Charlotte in the cooler Western Mountain region, featuring short multipitch lines such as Boardwalk (5.8); Airlie Gardens (5.9); and The Broach (5.11d), a thuggish climb known for its unrelenting 40-foot roof crack, developed in 1985 by Doug Reed, who established over 600 first ascents throughout the Southeast. Add it up and there are more than a dozen crags and over 1,000 published routes up this steely stone, all mercilessly steep, with cryptic gear, surreal horizontal features, intimidating roofs, and precipitous faces that demand power, and most importantly, mental endurance.

Shirts soaked and brows dripping, we hike down the improbable fourth-class gully that leads to the cliff base. The gully plunges into dense fog, the result of a temperature inversion that formed as the sun’s radiant energy warmed the cool, humid air. We creep down the damp gully through “pea soup” mist, accompanied by the sounds of dripping water and shifting rocks beneath our feet. Steep walls on either side of the chasm push in closer and gravity pulls harder as we maneuver around moss-covered boulders. This is a mysterious land more suited to hobbits and fairies than climbers.

Three hundred feet down the gully, we face a decision: negotiate a short fifth-class downclimb that is currently a waterfall or rappel 100 feet from an old-growth conifer. Decision made: As we rig our ropes, two climbers emerge from the fog. It turns out they’re from Asheville; soft-spoken and unassuming in their faded plaid shirts and tattered jackets, they ask if they can ride our ropes. “So, what are you working on today?” I ask them. A shrug of the shoulders and a delayed, noncommittal response reveals their objective: The Big Arête (5.11), put up rope solo in 2005 by Nathan Brown, a prolific first ascensionist. The line ascends a direct, overhanging path up a striking arête, ultimately connecting to an older, wild Doug Sword 5.10+ called Tall Order for a total of three full-value pitches. While The Big Arête is not a 5.15 media darling, it is an exposed, demanding climb that would be a proud tick on anyone’s list. But for better or worse, NC climbers, such as Brown, rarely seem preoccupied with only pushing grades or an all-out assault to conquer newsworthy lines. A bold, blue-collar mentality defines the climbing here.

Maybe it’s the heat and humidity or the isolation in these Southern hills, but NC first ascensionists often exude as much enthusiasm for not bolting a sketchy gear(less) 5.11 R as they do for equipping a hard crux with stacked pins. The Southeastern climber can be cantankerous and secretive, his persona often as difficult to breach as the rhododendron thickets that guard the cliffs. But with time and sincere questions about the area, you can uncover a shimmering enthusiasm from the old guard. They are quick to share twinkly-eyed accounts of favorite routes with near-photographic memory—describing a no. 5 Stopper that should be placed with the curve facing left, or using a 1980s rigid-stem Friend to protect a crux because the stiff lever action will improve the marginal horizontal placement. It is invigorating to listen to harrowing stories, embellished or not, of homemade-hex anchors, bold runouts, and shots of liquid courage taken to steel the nerves on audacious first ascents. Engage further and you might receive an invitation to one of the word-of-mouth, unpublished, four-star quartzite crags that seem to propagate in North Carolina.

Off rappel with our feet on the gorge floor and ropes coiled, we part ways with the Asheville duo and start the final push to Julia’s base. It’s only one-tenth of a mile, but it might as well be 10 miles because of the wet, impenetrable bush. Lee pushes forward 15 feet ahead. I can see nothing—not a single square inch of his bright-purple hoody. Like so much of this gorge, charred by recurring fires, the undergrowth is gnarled, forcing us to blindly plant each shoe in the loose, blackened soil. With the fog lifting and approach ending, my thoughts transition to Tom Howard, who helped establish Julia in 1977, plus reams of other classic NC climbs. I imagine Tom pulling a thorn from his thumb (as Lee has), blood gushing, nearing the corner that will soon become Julia. Did he and Bruce Meneghin argue, like us, over who would get pitch one, with its striking fingertips corner? Did he pause at the base staring, wide-eyed, eager to chart a new line up this wilderness cliff? What I do know, after climbing many of Howard’s Shortoff routes, like Dopey Duck (5.9), Straight & Narrow (5.10a), and Built to Tilt (5.10b), is that he had an eye for classics and an even better hand at leaving those classics intact, with minimal impact. Loose rock, lichen-covered holds, and laurels growing from the nooks—we will experience it all today, along with stellar movement and beautiful rock features.

Lee wins the debate over who’s taking the first lead and steps over the laurel that guards the starting crack. My jealousy quickly gives way to a focused belay as he nears the crux, 70 feet off the ground. Utilizing his 6’2” wingspan, Lee places a tightly cammed piece, downclimbs to quiet the mind, and then fires through the marbled stone. One hand with tips wedged into the thin seam and the other pressing against polished, milky quartz, he stems through one powerful sequence after another to reach the final corner bulge. “Watch me!” Lee yells down. He thrutches, trying to beach-whale over the bulge well above his last piece, then suddenly I’m pulled up and off the belay. Lee hangs there then steadies himself for a second and successful attempt. Crux pitch behind us, we move through sustained 5.9+ terrain on the upper two pitches, which I string together as one.

Lee and I top out just as we started: in the canopy.

I sit, shoes off, contemplating others who have grasped the same holds and enjoyed similar, solitary days. What stories, bygone and contemporary, have played out in this lush, bucolic place, and how will new adventures unfold? Warmed by the late-afternoon sun, I can see again the intimacy of the North Carolina landscape through an endearing confluence of light, shadows, and topography. Lichen still clinging to our shoes and chalk on our hands, Lee and I savor the moment just as we have for the past 20 years climbing together—very few words and a quick shake of the hands.

In the beginning of my North Carolina climbing journey, I cursed these ancient, eroded mountains. I would return home from each trip with cuts and bruises, covered in bug bites or forced to explain to co-workers why my hands and legs were shredded and battered. Always sharing stories with family, often embellished, like the time we climbed Maginot Line (5.7) on Shortoff Mountain and had to battle an angry copperhead mid-pitch. Or the time we were blown off Ship Rock due to gale-force winds. But it happened. These types of adventures almost always happen here—it’s raw, plain and simple. Just as these rock walls grow lettuce-leaf-sized lichen, so grows in anyone who climbs here an enduring love for this mysterious green climber’s playground.

North Carolina’s Top Quartzite Crags

Moore’s Wall

This 200-foot cliff bursts from the hills of the North Carolina Piedmont. It’s generally regarded as a place for the experienced leader due to tricky gear and runouts.

Season

Year-round. However, at 2,579 feet and facing northwest to northeast, Moore’s can be exceptionally cold in winter.

Location

North, central Piedmont, approx. 30 minutes from Winston-Salem.

Camping

Hanging Rock State Park. Camping is not allowed at Moore’s Wall or in the climbing-access parking lot.

Restrictions

All climbers must register at the climbing-access trailhead.

Pilot Mountain

A popular winter destination with approx. 80 routes and easy access. Can be crowded on winter weekends.

Season

Year-round, though summer can be hot due to the cliff’s aspect.

Location

North, central Piedmont, approx. 30 minutes from Winston-Salem.

Camping

Pilot Mountain State Park; (336) 325-2355.

Restrictions

All climbers must register at the climbing-access trailhead.

Crowders Mountain

Often referred to as “Crowded” Mountain, this cliff is generally regarded as a locals’ crag, though it does have high-quality 5.10 and 5.11 mixed lines.

Season

Year-round, though summer can be extremely hot.

Location

South, central Piedmont, approx. 45 minutes west of Charlotte.

Camping

Crowders Mountain State Park; (704) 853-5375

Restrictions

All climbers must register at the climbing-access trailhead.

Ship Rock

With grades from 5.7 to 5.12 and roughly 70 routes up to 200 feet high, this is a worthy stop for any trad climber seeking cooler temperatures and steep rock.

Season

Spring through fall. At 4,592 feet and facing primarily northwest, Ship Rock is an ideal summer crag.

Location

Northwest Mountain region, approx. 30 minutes southwest of Boone.

Camping

Julian Price Memorial Park. Camping is not allowed on Ship Rock.

Linville Gorge (Shortoff, Amphitheater, NC Wall, Table Rock)

This is why you come to North Carolina! While the Linville Gorge is a popular destination, it still offers a true wilderness experience for the multipitch trad climber, with more than 250 routes from 5.4 to 5.12. Come prepared to battle at any grade.

Season

Spring through fall.

Location

Western Mountain region, approx. 1.5 hours east of Asheville.

Camping

Free inside the Linville Gorge Wilderness. Overnight-use permit required on weekends and holidays from May 1 through October 31. Contact: District Ranger-US Forest Service; (828) 652-2144.

Restrictions

Peregrine falcon closures apply. Visit carolinaclimbers.org.

Essential Gear

Scarpa Iguana

“You need a shoe that’s agile for the steep, technical approaches, but also lightweight to clip off to your harness,” says Miller. The Scarpa Iguana weighs 18 oz per pair, with clip-off loops and a Vibram Reptilia MG sole to crush the approaches. $120, scarpa.com

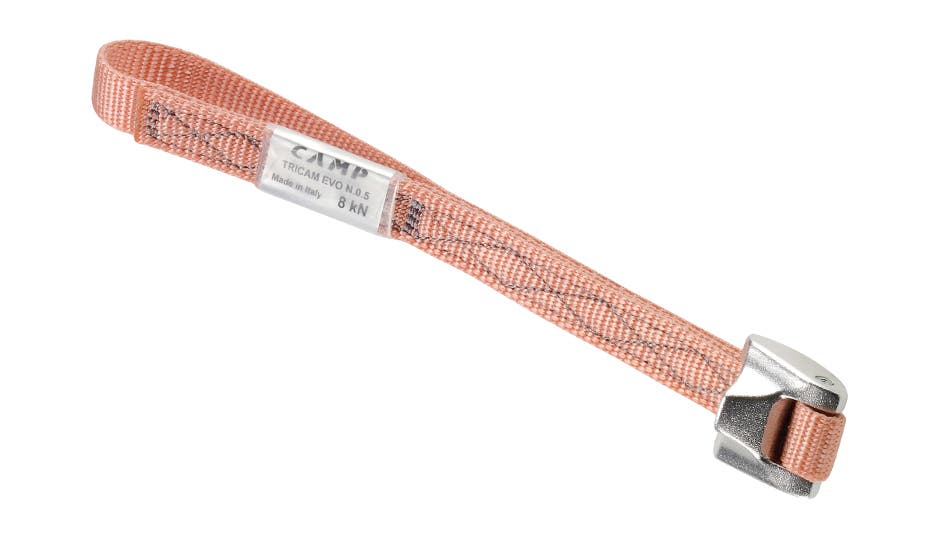

C.A.M.P. Tricam

Says Miller, “Tricams are incredibly useful for the irregular horizontal slot features where cams tend to open too wide.” He specifically recommends the black (0.25), pink (0.5; pictured), and red (1) for NC’s quartzite. $24–70, camp-usa.com

Misty Mountain Turbo Harness

For NC’s steep trad pitches, you’ll often be harness-racking. The lightweight Turbo packs small for long approaches and then helps you sort your rack with four ample, webbing-reinforced ¼” PE tubular gear loops. $105, mistymountain.com

“Trad Draws”: Black Diamond 10 mm Dynex Runners and Oz Carabiner

“It’s almost mandatory to carry 24s since you’re constantly clearing big, sharp features,” says Miller. Pair them up with the 1-ounce Oz wiregate. $9 for 24” runner, $9 per biner; blackdiamondequipment.com

Black Diamond Micro Stoppers

“You really only need these for the hard 5.10s on up,” says Miller. He carries BD’s Micro Stoppers in sizes 2, 3, 4, and 5, preferring their superior holding power over the tiniest, size 1. $16 each, blackdiamondequipment.com

Bryan Miller owns Fixed Line Media, a climbing and adventure-content company based in Charlotte, North Carolina.