Stoney Point: Portrait of an American Crag

"Stoney Point: Portrait of an American Crag"

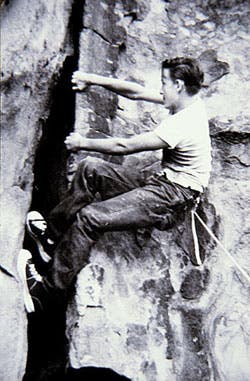

“When you grab an edge at Stoney, you’re touching a hold Royal Robbins caressed. When you step on a hold, you could be adding your boot scum to that of Bob Kamps. When you peel off Boulder 1 and land in the dirt, you’re thumping where Yvon Chouinard did.”—John Sherman, Stone CrusadeIn late 2005, when I was a senior at the University of Southern California, new to rock climbing and greener than Gumby, those words would have meant nothing to me. Royal Robbins? Bob Kamps? Who are those guys? If you told me that Robbins climbed the first 5.9 in the country, or that Kamps put up some of the first 5.11s, I might have retorted, “5.11? Big deal. everyone climbs that grade.” Chouinard? He was that surfer guy who started Patagonia in my hometown of Ventura—was he a climber?

Ignorant as I was about climbing’s heritage, I never would have guessed that few crags in America could compare in richness of history to my local crag, Stoney Point.

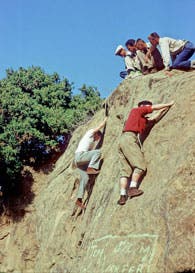

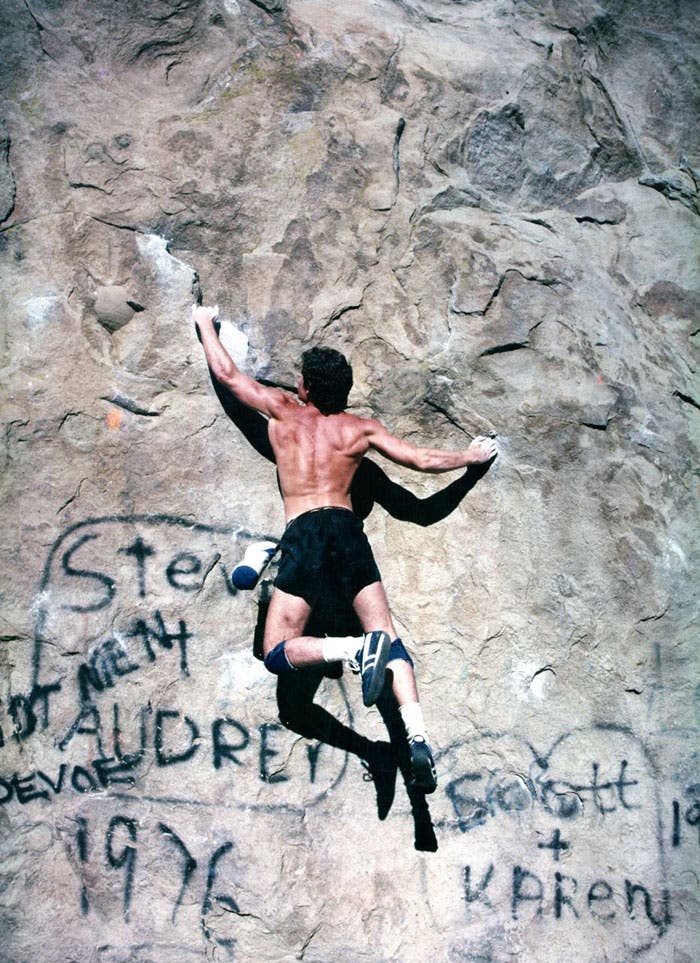

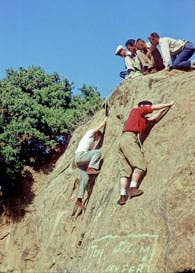

Located roughly 15 miles northwest of the Hollywood sign, Stoney Point’s graffiti-stained cliffs rise above the town of Chatsworth like an ancient rampart. From Stoney’s modest peak, the entire San Fernando Valley is visible—a grid of streets, giant shopping centers, and beat-down storefronts stretching as far the eye can see. Almost 10 million people live within a half-hour drive, and with more than 300 days of annual sunshine, Stoney Point sees more traffic on a weekend than some crags do all season. The short cliffs and plentiful boulders have served as Los Angeles’ free outdoor climbing gym for more than 80 years, and some of the most prominent climbers in our sport got started here.

The rock quality at Stoney Point isn’t exactly world-class. The sandstone is too soft for sport climbing, and boulder problems change character on a regular basis as holds break. There are a handful of leadable trad climbs littered around the park, but most climbers spend their time bouldering and toproping. Though soft, the unique sandstone here produces a wide variety of interesting features, and just about any style of free climbing can be practiced.

Some are quick to hate on the broken glass, graffiti, and sometimes chossy rock, but those willing to put aside their preconceptions and climb classic, sandbagged problems in a historic setting will soon understand how Stoney Point earned its place in the history books.

As a young novice scumming up Boulder 1’s finest warm-ups with footwork akin to a newborn moose, I had no clue that climbers had been training on that same rock in the early 1930s. At that time, Stoney Point was the laboratory for the Sierra Club’s pioneering efforts to refine the latest in modern roped climbing and belaying techniques.

Glen Dawson led many of the club’s first outings to Stoney Point. Famous for a string of first ascents in the Sierra, including the

East Face

(5.7) of Mount Whitney in 1931, Dawson had plenty of experience at the cutting edge of the day. I got a chance to pay a to the 97-year-old Dawson at his retirement home in Pasadena, California, in 2008. Still sharp as an ice axe, Dawson enjoyed reminiscing about his old stomping grounds.

“One of my most pleasant experiences was climbing and jumping and rappelling at Stoney Point,” he told me. “It was a beautiful location, and we had lots of good times out there. It was easy to get to, was used year-round, and a lot of the early climbers began their climbing there.” Dawson wasted no time in sharing his collection of sepia-toned photos of fedora-topped men with hemp ropes climbing all over the Point.

The more I climbed out at Stoney Point, the more intrigued I became with its history. While the guidebook provided a few basic stories and facts, the real gems were told by old timers during weeknight bouldering sessions. Oral tradition is as strong now at Stoney Point as it was when Native Americans inhabited the area millennia ago.

1950: as the rest of the world began its slow rebound from World War II, a 15-year-old Royal Robbins was hopping freight trains and looking for adventure. Robbins would go on to become one of the country’s most prolific and influential rock climbers, but at that time, he barely knew how to belay. One day, when the train slowed down on a big curve next to Stoney Point, he couldn’t help but jump off and take a look. I was lucky enough to visit with Royal in July 2010, and he told me all about his early days at the Point.

“I went there often because I could picture the future, which was big mountains,” said Robbins, “and this was a way of getting to the big mountains. And so I would go to Stoney and develop myself, develop my strength and my abilities in ways I never knew I could do.

“We didn’t have any climbing gyms in those days, and Stoney was the place. It’s where it was happening, and you could get there just like that.”

Also around this time, a young falconry practitioner named Yvon Chouinard first came to Stoney Point to learn the techniques for rappelling into falcon nests. During one of his visits, he saw people rock climbing for the first time. Chouinard was fascinated, and before long, he too was hopping freights from his home in Burbank to climb with Robbins and other would-be hardmen. One of his 1950s testpieces is

Chouinard’s Hole

(V2), a quintessential Stoney Point sandbag.

Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, early California climbing pioneers including Bob Kamps, TM Herbert, Tom Frost, Chuck Wilts, and Mark Powell used Stoney to refine the skills that would later make them legends. One important skill was piton-craft. With the clean-climbing revolution still years in the making, training for Yosemite’s big walls involved practicing aid techniques, especially the placement and removal of pitons.

Consequently, every fissure from legitimate finger and hand cracks to sandy, incipient seams took repeated beatings. Evidence of this almost maniacal desire to pound pins is chiseled into the sandstone, petroglyphs from a barely remembered culture. And while there are strict stylists at Stoney who refuse to ever crimp a chipped hold, most don’t mind running laps on such pin-scarred classics as Three Pigs (V0) or Sudden Impact (V6).

While the ability to place a piton that could actually hold a fall was crucial, not falling in the first place was preferred. Therefore, from the 1930s onward, climbers spent the majority of their time at the Point bouldering. Popular challenges of the 1950s and ’60s included no-hands ascents, and competitions to see who could carry the largest rock to the top of Boulder 1. Similar traditions live on today, and on weekday nights you’ll see groups of boulderers surrounding a problem, seeing who can create the most vicious eliminate. For Robbins, Chouinard, Kamps, and the rest, such bouldering sessions led directly to groundbreaking first ascents, where advanced freeclimbing techniques helped turn dream climbs such as the Salathé and North America walls on El Capitan into reality.

Robbins and Chouinard later went global, establishing bar-raising first ascents like the American Direct on the Drus in the French Alps (Robbins) and the California Routeon Fitz Roy in Patagonia (Chouinard). Other Stoney Point locals were happy to keep the home fires burning—especially Bob Kamps.A free-climbing master, Kamps was a fixture at Stoney Point for 50 years, cultivating a mastery of footwork and movement over stone as artistic as a Van Gogh brushstroke, and sometimes just as tortured. “Bob Kamps had an amazing capacity to do very strenuous, painful moves,” says Stoney Point regular Mike Flood. “If it required a one-thumb move or a tucked mantel where his hand was right in his chest, this man could pull it. He had a lizard-like contact with the rock.”

With his climbing prowess, strict traditional ethics, and humble attitude, Kamps was a role model for countless climbers, and climbed at a remarkably high level right up to the end of his life. Well into his 60s, Kamps could cruise the strenuous V5 roof traverse Hot Tuna. A source of inspiration and pride for three generations of Stoney Point climbers, Kamps died in 2005 a few months before I laced up my first pair of climbing shoes. His legacy lives on at Stoney through many stories—and some of the most heinous mantels and eliminates you could imagine. Have a local show you Kamp’s Mantel (V-baffling), and you’ll see what I mean.

Around 1970, an athletic, blond-haired teenager started showing up at Stoney Point. John Bachar was on his way to becoming the greatest free climber of his generation, and spent his formative years at the Point absorbing all he could about footwork and technique from locals like Kamps and Jim Wilson. “When I started climbing,” long-time local Jan McCollum remembers, “Bachar was already here. He was in high school. He was already better than everybody else. He was slow, precise, perfect.”

Bachar took Stoney Point climbing to new levels, with classic first ascents like the powerful Ummagumma (V6). Legend tells of a skinny John Bachar, a lifelong training fanatic, madly curling weights in his beat-up van as he drove down Topanga Canyon after exasperating bouldering sessions. Not long after moving away, Bachar would lead the climbing world to new heights with countless cutting-edge first ascents and outrageous free solos up to 5.13.

Not alone in his quest to set the climbing world on fire, Bachar was part of something much larger than himself: the Stonemasters. The first time I heard about this infamous group was at Stoney Point’s Turlock Boulder. Two old guys sat passing a honey-bear bong, telling mythical tales of men 10 feet tall who, despite the disadvantage of 50-pound testicles, could do hundreds of one-arm pull-ups.

Throughout the 1970s, this cadre of young Southern California climbers blew through Joshua Tree, Tahquitz, and Yosemite hotter than the Santa Ana winds, leaving a lasting legacy of hard climbing. Though never “true” Stoney locals like Bachar, other Stonemasters including John Long, Lynn Hill, and John “Yabo” Yablonski spent their fair share of time bouldering at the Point. Long left behind the crimpy Largonaut (V6), while Yabo established five-star classics all over the park, including what might be the prettiest line of them all—the intimidating and hard-as-nails Yabo Arête (V8).

With Stoney being Southern California’s busiest local proving ground, the obvious question arises: “Who is the strongest?” Fortunately, no one has had to ask that question for more than 30 years. Everybody knows the answer, and it never changes: Mike Waugh. Waugh has been seriously referred to as the world’s strongest man. As Bill Leventhal puts it, “Mike Waugh had just the most amazing hydraulic power of any climber I’ve ever seen. More than Bachar, more than Dale Bard, more than Ron Kauk. Just with one arm, [he’d] grab the crappiest hold and pull it to his chin with no feet. Amazing. He was hands down the most powerful climber I’ve ever seen.”

At 53 years old, Waugh still has Stoney Point wired like a harp and can complete just about any problem in the area. He’s also the go-to guy for beta on California’s most notorious “death-pieces.” He’s done them all, including multiple romps up the rarely done The Edge (5.11 R) at Tahquitz and the infamous Bachar-Yerian (5.11c R/X) in Tuolumne Meadows.

The 1980s and ’90s saw rock climbing evolve from a fringe activity practiced by few to a quasi-mainstream sport with ever-increasing numbers, and Stoney Point witnessed a huge influx of new talent. With fresh vision, Bill Leventhal, Matt Oliphant, and Vaino Kodas had the gumption to create an entirely new circuit of psychologically demanding bouldering on the often-ignored backside of the park. To this day, the mantel lurking atop Kodas Corner (V3) separates the men from the gym rats on a weekly basis. This group also established a slew of demanding topropes, including Scurf and The Dart Lady(both 5.12), which, due to a lack of big overhangs and blank faces, remain two of the harder roped climbs in the area.By the 1990s, a majority of the obvious plums hanging around the 14-acre park had been picked. A climber needed exceptional strength and creativity to find and complete new lines. Jeff Johnson had both. Accompanied by a talented group including Paul Anderson, Dimitrius Fritz, and Aaron Sandlow, Johnson elevated Stoney Point bouldering to a new level. “Jeff?” Fritz recalls. “Probably the best climber I’ve ever climbed with in my life. Strongest mentally, physically. Vision. He could instantly see the line. Yeah, Jeff was the guy.”

Johnson brought an uncompromising style (no stacked pads, if any at all, and a ground-up philosophy) to bear on the Point. Longstanding projects like the Johnson Problem (V7) dropped faster than Euro sport climbers from an off-width, and new-wave classics like the sloper nightmare The Font (V7) and the fiendishly crimpy Fritz Face (V7) finally went down.

“Oh, c’mon! Press it out!” I started back up. Committing, I threw my heel, swung over the lip, and shakily began to mantel onto the hold. Stuck in limbo between pressing up and falling ass backward 20 feet to the ground, I heard the voice again, urging me, “Press it out!” I shifted my weight, finished the mantel, and made the last few easy moves to the top of the boulder. With eyes wider than a Big Bro, I looked down to see none other than the great Michael Reardon smiling back up at me. “See?” he yelled. “Not that hard!”

Notorious for onsight free-solos such as the 10-pitch Needles testpiece Romantic Warrior (5.12b), Reardon, a Stoney regular, was sometimes portrayed as arrogant. I met Reardon out at the Point a few times, and though definitely self-assured and willing to speak his mind, he was always friendly and encouraging. Few would argue that he is sorely missed around Stoney Point

Today, the vibe out at the Point is much like I suspect it was 50 years ago when Robbins and Chouinard ruled the place. On weekends, cars line Topanga Canyon Boulevard, as noobs and veterans alike take part in the same addiction. Every Tuesday and Thursday, a core group of locals gets together after work to drink beer, talk shit, and sometimes even climb. New members are always welcomed.

In a world of mutant strength, gym climbers, and double-digit boulder problems, Stoney Point might seem like nothing more than an antiquated, dumpy little area on the side of the road. Most of the classic problems lie between V3 and V8, and there’s not much left in the way of newsworthy first ascents. But pristine surroundings and number chasing have never mattered as much at Stoney Point as a daily dose of training and forming friendships. It kills me every time someone at the gym tells me he’s never been to the Point because he’s heard there’s broken glass and graffiti. This comes with the territory—the rich history of Stoney Point can be directly linked to the sheer number of people amassed nearby. Sadly, not all of them are as respectful of the park as the rock climbers.Despite the urban setting, there’s something special about this place that builds strong climbers as well as a tight community. Whether it’s the amount of climbable rock or the always-encouraging atmosphere, I really can’t say for sure, but from Yvon Chouinard and Yabo Yablonski to the Sierra Club and the modern Tuesday-Thursday crowd, the entire spectrum of American climbing has played out in this small park on the outskirts of L.A.

Cole Gibson is a first-time contributor to Climbing and is currently wrapping up a documentary on the history of Stoney Point climbing (stoneypointdocumentary.com).

Three Pigs

(V0), Boulder 1, east face. Everyone’s first V0. This pin-scarred classic is a gift that keeps on giving! Locals spend many a happy evening honing the sequence down to the absolute minimum. Eliminates are possible, of course, as well as a sit start.

Hoof and Mouth (V1), Turlock Boulder, east face. A solid classic with a big move out of the “mouth” to the lip. An old problem that used to be rated 5.8!

Pump Traverse (V1), Pump Rock. A footdragging lowball; pumpy and hard for V1, but on great rock.

Spiral Traverse (V1), Spiral Boulder, west face. The local crimpy stamina trainer, ruthlessly wired by many locals. Unofficial record for laps there and back without stepping off: 26.

Sculpture’s Traverse (V1), Sculpture’s Crack Area. Start on the right with a problematic layback crux, then follow the handrail to a long reach and Sculpture’s Crack.

Quickstep (V2), Mozart’s Wall area. Multiple foot switches lead to a heel hook and committing move to a big jug. The real commitment is next: topping out.

Maggie’s Traverse (V2), Nabisco Canyon. Classic 100-foot traverse with V2 cruxes at the beginning and end: an endurance test with some power moves at the start and a smeary finish.

Boot Flake (V2), Boulder 1, west face. This highball V2 teaches you how to crimp, 1960s-style. Although it’s technical up to the Boot, the upper section really gets your attention. Finish direct rather than bailing left onto the upper ledge. Variations include traversing left at the Boot (same grade) and the spectacular, tall Double-Dyno (V6).

Yabo Roof (V2), Turlock Boulder, northeast corner. Committing crux move way up high. Some people think it’s V4; if you’re shorter, that crux reach for the knob on the lip might be a dyno.

The Crack (V3), B1 Boulder (not to be confused with Boulder 1). A great introduction to the B1’s overhanging problems. Big pulls on good but widely spaced holds, with a thought-provoking topout. Eliminate the deep pocket on the right for a popular V5.

Kodas Corner (V3), Canyon Boulders. Leaning, rounded arête with a stout mantel at the top. Engaging the whole way—a beautiful problem.

Crystal Ball (V4), Turlock Boulder. Great movement, highball, full value. Reportedly John Bachar’s favorite problem here—a classic line on what is probably Stoney’s best boulder.

Yabo Mantel (V4), Boulder 1, east face. Hardest V4 ever! Mantel tenuously onto a giant sloping shelf. Avoid the big chipped crimp to keep it real.

Kamps’ Mantel (V-Kamps), Slant Rock. An eliminate, which was Bob’s specialty. Mantel onto a crimp in the middle of the north face. Locals won’t let you say you did it unless you calmly chalk up after you’ve manteled onto your hand—this way you have to do it static.

Masters of Reality (V5), B1 Boulder, west face. The guidebook aptly describes this as “Zen and the art of bouldering.” Cool, subtle opening moves to a burly topout.

Hot Tuna (V5), Hot Tuna Area. A true rite of passage. This 40-foot-long, overhanging roof/lip traverse is as greasy as it is classic. The big dyno at the very end keeps many shorties from sending.

Sudden Impact (V6), Sudden Impact Boulder. Overhanging pin scars over a badly sloped landing—this had a reputation for quite some time after the FA. Classic!Leaping Lizards (V5), Boulder 1. One of the many diversions in this popular zone; a huge dyno from sidepulls past the Yabo Mantel to a big jug.

Powerglide (V6), Eat Out More Often area. Stoney’s V6 crimp testpiece. Hard and classic 1970s problem.

Ummagumma (V6), Ummagumma Boulder. A big move between solution pockets, then a slopey topout. Stout.

Johnson Problem (V7), Split Rock. An obvious, longstanding project with a big, tricky crux move that denies many a strong climber. Tall.

Fritz Face (V7), Canyon Boulders. Modern and powerful. Sit start to undercling, bad crimps, a sloping lip, and finally a semi-jug.

The Font (V7), Canyon Boulders. Short, desperate sloper hell on perfect rock.

Yabo Arête (V8), Blockhead Boulder. This tall, clean arête shares honors with Kodas Corner as one of Stoney’s most elegant lines.

Ed’s Direct (V8), B1 Boulder. Left of The Crack. Sit start using the big, rounded undercling, up to a small pocket, then straight up past a sidepull.

Fighting with Alligators (V10), Ummagumma area. North side of the boulder that rests against Ummagumma. Sit start to outrageous lip traverse right. Massively burly.