Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

When summertime highs hit the triple digits, even the most hard-core climbers lose enthusiasm for chasing shade at their local crags. So this summer, ditch the draws and cams, unearth your bikini and board shorts, and find a climb over deep, cool water. You don’t have to fly to Mallorca to experience deep water soloing. Below, some of North America’s favorite “psicobloc” destinations. Note: Some of these areas have laws and regulations governing cliff jumping—solo at your own risk. Always check water depth and probe for underwater rocks, logs, and other obstacles before climbing, and be aware of other recreationalists, especially boaters.

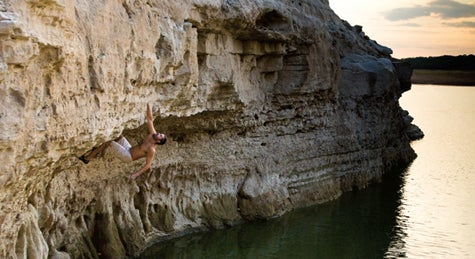

Lake Travis Pace Bend Park

Austin, Texas

Texas’ suffocating summer heat drives hordes of climbers to Lake Travis, about 30 miles west of Austin. Some rent boats to access the climbing, although most leap from the top of the limestone cliffs, which range from 15 to 40 feet, or downclimb to the lake. “The true fun is pulling straight out of the water,” says John Hogge, who’s working on a guidebook to the area. “It’s unusual and interesting managing footholds underwater.” Climbing style includes “technical face moves” and “overhanging jug- and tufa-hauls,” says local Paul Brady. Climbs range from easy to expert, and water landings can be very safe, but Brady urges climbers to use a depth finder or pole to check the landings before climbing. Lake Travis is climbable all year, but summer is best, with water temps hovering in the 70s. “It makes the 100ºF days feel much cooler,” Brady says.

Beta

Access to the park includes a $10 entrance fee per vehicle per day ($2 additional with a boat). Check bloodyflapper.com for crag locations and current water levels.

Lake Powell

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah

With 2,000 miles of shoreline (more mileage than the continental West Coast), Lake Powell has “rock literally everywhere, with wide-open potential,” says Josh Thompson, who has spent several weeks at the lake. Cliffs up to 500 feet tall jut out of the water, comprised mostly of Wingate and Navajo sandstone. When the water level is down, an obvious “bathtub ring” appears, where the rock appears bleached and chossy. But “a lot of the weak and loose rock gets washed off while underwater,” Thompson says. “When it dries out, it’s strong.” There are varying styles of climbing, including overhanging faces, crack climbing, and even huecos. Bolts are banned, so there aren’t established routes—simply pick a line to solo and go! “The entire Escalante Arm is lined with cliffs and potential,” Thompson says. “If you have a boat, it’s very easy to climb at lots of different places on the same day.” Because of the lake’s huge size, it’s recommended to rent a houseboat from one of the six Lake Powell marinas for exploring.

Beta

Check lakepowell.com for boat rentals, weather, and other useful info.

Kinkaid Lake

Jackson County, Illinois

Along the shore of Kinkaid Lake, near Murphysboro, a 500-foot-long sandstone cliff provides excellent climbing. “The rock is impeccable quality,” says Kinkaid developer Aaron Brouwer. “It’s very, very clean.” The cliff rises out of the 2,750-acre lake from right to left (“You can swim over and get right on the rock from the water,” says Brouwer. “It’s a perfect slope”), and it tops out at just over 60 feet. About 30 routes and 10 boulder problems litter the overhanging wall, offering everything from slopers to crimps and pockets, and the average water depth at the base is about 20 feet. Climbers can access the wall from a boat or use a trail that runs straight down to the waterline. There’s not much in the way for beginners—the easiest climbs start at 5.10+.

Beta

Kinkaid Village Marina (618-687-5624) offers boat rentals and camping sites, or camp on U.S. Forest Service land.

Banks Lake

Grand Coulee, Washington

Washington State doesn’t exactly conjure Euro-style images of deep water soloing. But water pumped from the Columbia River into the Grand Coulee basin created Banks Lake (about four hours from Seattle or two from Spokane), where you’ll find granite and basalt outcroppings rising from the water, forming mini-islands; much of the lake is surrounded by black basalt walls. Boat rentals are necessary to access the climbing. For the faint of heart, bolted lines litter the canyon walls, and belaying from the boat is possible. The climbing style varies: “The granite can be very sequential and funky, with slopers and limited features,” says Audrey Sniezek, who lives in Seattle. “The volcanic basalt tends to have more crimps, edges, and pockets.” Cliff heights vary from 10 to 40 feet tall along the 27-mile-long lake, and water landings are typically deep—but be sure to jump outward when climbing less-than-vertical walls. When the summer temps soar, the water stays cool in the mid to low 70s.

Beta

Camping is available at Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife–designated sites, or head to Steamboat Rock State Park. Boat rentals are available at the Sunbanks Resort (sunbanksresort.com).

Heaven

Cheakamus River, Squamish, British Columbia

Located halfway between Squamish and Whistler on the Cheakamus River, you’ll find overhanging climbs on Heaven’s 30-foot granite cliffs. Another destination with cold water, this place is best visited in high summer, or with a wetsuit in earlier months. To access the routes, climb down the east riverbank to white granite slabs “that heat up with the sun and warm your cold-nipped body,” says Squamish local Matt Maddaloni. Swim across the clear, emerald-green water for more routes, surrounded by old-growth forest hanging over the river. Routes range from beginner to expert. With the cold water and sometimes-strong river current, good swimming skills are recommended.

Beta

Located just downstream of the Rogue’s Gallery climbing area off Highway 99. Park at Rogue’s and walk 10 minutes south—turn on a dirt road (foot traffic only) that drops down parallel to the highway for about 1,000 feet. A path leading to the water will bring you to the top of the cliffs, then find your way down to the slabs.

Devil’s Punch Bowl

Roaring Fork River, Independence Pass, Colorado

Situated in a beautiful alpine setting, the Punch Bowl’s icy waters provide a welcome respite from Colorado’s stif ing summer heat. About 10 miles from Aspen and off the road to 12,095-foot Independence Pass, this idyllic pool is surrounded by granite walls. To access the climbing, either take the 35- to 40-foot plunge into the water and climb out, or downclimb an easy crack about 20 feet downstream—during the summer season, there’s often a fixed rope. Warm up on easier lines on coarse granite on one side of the bowl, then sack up and swim to the other side, where you’ll find water-polished climbs up to 5.12, with high cruxes. “One of the better lines there requires a committing deadpoint, almost a dyno, about 25 feet above the water,” says Jim Sellers, who frequents the area every summer. Sunny granite slabs beckon after swimming—due to its high elevation and mountain runoff, the water is always cold.

Beta

From Aspen, follow Highway 82 toward Independence Pass. Turn right onto Lincoln Creek about 7 or 8 miles out of Aspen. You’ll be on a dirt road for about three miles; find a huge granite slab on the left and park there. The Punch Bowl is about 100 feet back down the road on the other side.