Roped Up in Arabia: Rock Climbing in Jordan

"Wadi Rum Jordan Rock Climbing"

This story originally appeared in the August 2014 issue of our print edition.

Wadi Rum, a vast, echoing labyrinth of brick-red sand and castellated cliffs in southern Jordan, lies deep in the cradle of civilization. It feels like the epicenter of the universe—in both a spiritual and a climbing sense. The climbing I can explain; you’ll just have to trust me on the spiritual thing. It’s the ultimate in adventure climbing—a blend of Canyonlands cracks, Yosemite big walls, and Black Canyon commitment, with a vibe that’s totally Arabia. The climbing here is mainly trad on big sandstone formations (the longest routes are more than 600 meters and nearly 30 pitches), and is characterized by a bold, committing style. There are long runouts and airy traverses, and the rock quality can go from hard to soft in a matter of moves. Protection can be tricky. This is desert alpinism, with intricate scrambles up low-angle ramps to spectacular 1,800-meter summits via traditional Bedouin routes. And the collection of 5.5 to 5.11 cracks may be one of the finest in the world. There are steep, 12-pitch 5.12 and 5.13 testpieces, some bolted, some not. The clean-climbing ethic is strong here, although most of the classics now have fixed anchors. Route-finding is tricky, and descents can be complex and technical. But the climbing is spectacular. There are corners, dihedrals, arêtes, and towering faces all made accessible by endless cracks, hidden chimneys, pockets, and knobs. The mountaineering and climbing are world-class and the bouldering unexplored.

The Wadi Rum Protected Area is about four hours south of Amman and an hour north of the Red Sea port of Aqaba. It extends south to the Saudi Arabian border. The Bedouin village of Rum is located in the center of this vast maze of domes and cliffs, at just 950 meters above sea level. From both sides of the village, the massive ranges of Jebel (mountain) Rum and Jebel Um Ishrin rise to a height of over 1,700 meters, casting cathedral-like shadows across the sun-scorched sand.

The climbing community in Jordan is surprisingly strong. Perhaps it’s due to the difficult conditions in the surrounding countries that have led Jordan to develop a legit climbing culture that’s coming into its own. Surrounded by hot spots like Syria, Iraq, Israel, the Palestine Territories, Iran, and Egypt, Jordan has developed arguably the strongest (and certainly the friendliest) climbing community in the Middle East. In Wadi Rum, you’ll find climbers from Dubai and Israel, some who are refugees from Iraq or Syria, and some who drive down from Amman. The area is shifting from the realm of multi-month expeditions and elite climbing teams to a viable destination that has something for everyone. In Jordan, climbing is a common language of peace, fun, and adventure ripe for exploration—just bring your own pro, sunscreen, and camel harness.

Amy Jurries, a fellow climber, writer, and founder of popular site thegearcaster.com, and I trailed Mohammad Hammad out of his home in Rum Village. The village is as close to the Star Wars planet Tatooine as you can get. Tents, camels, goats, and houses are surrounded by walls that separate properties from one another. There are a lot of children—some families have as many as 20. Many of the locals are related—cousins, siblings, aunts, and uncles—and most work in the local tourism business. From camel, horse, and jeep tours to hikes, scrambles, and climbing, there is plenty to do in Rum. Local outfitters also provide trekking and camping services—from tents behind the Rest House to luxury “private” camps tucked far into the desert.

We’d spent a half hour convincing Mohammad of our climbing prowess, trying on ill-fitting helmets and assuring our press-trip handlers that a five-pitch desert climb was not dangerous. In contrast to the other Bedouin men in the village, with their crisp ankle-length robes, traditional Jordanian red and white headscarves (black and white are Palestine’s colors), and sandals, Mohammad sported white soccer socks, plaid Bermuda shorts, and a blue polo shirt. He wore his scarf tucked up into a tight-fitting turban (keffiyeh) wrapped Bedouin style. My Cheshire grin masked some concern. In more than 30 years of climbing, I’d never relied on a guide. Amy and I had never roped up together. And Mohammad was clearly sick with serial fits of coughing. Our plan was to climb the four-pitch Goldfinger (5.9).

The East Face of Jebel Rum towers 1,700-plus meters above the village of Rum. The walk to the base takes 15 minutes—much of it along a narrow stone wall that traces the edge of Nabatean ruins dating back to at least 300 B.C. Amy and I helped carry the gear, and as I started to flake out the rope, Mohammad looked on apologetically. “The rope is bad,” he said, shaking his head. “It got wet in the canyons. It’s only good for a camel harness.” Amy and I stared up the sheer face, and then looked at each other with saucer eyes. We eyed Mohammad closely as he tied in. The sheath was impressively frayed and the cord goldline stiff, but what we didn’t know was that the local Bedouins are known for their keen sense of humor. He took off climbing—moving with confidence, talent, and fluidity.

Goldfinger is a beautiful route following an obvious crack system on the finger-shaped towers clinging to the East Face of Jebel Rum. The climb begins with a scramble up to the white rock band and the start of the crack system. The third pitch is the crux, a chimney that demands classic push-and-pull technique. The well-featured rock made climbing fun, with plenty of pockets, knobs, and small crack systems, including abundant opportunities for natural protection. To my left was a monster splitter that rivaled Supercrack in Indian Creek.

Mohammad placed nuts as adeptly as if he’d been raised in Yosemite. He slung chickenheads and threaded runners through rock channels left by wind and water. I was surprised to see no fixed anchors. The rock was stellar until we reached the top where a mammoth-sized boulder guarded the path between us and the belay. Suddenly the route went from casual jug-hauling and stemming to those tricky, hold-your-breath levitations I’d learned on fragile rock in Canyonlands.

I first heard of Wadi Rum during the first Gulf War when I had just started as a junior editor at Rock and Ice. One of the earliest stories I’d worked on was by a U.S. soldier stationed in Iraq who climbed in Wadi Rum during his leave. I don’t know what happened to the soldier, but I never forgot his snapshots. Fast-forward to 2013. As a writer, I travel in search of stories. This time, I was invited on a media trip to Jordan. Jordan? I was intrigued and nervous. Most U.S. media coverage on the Middle East is consumed with the riots in Egypt, civil war in Syria, conflict between Israelis and Palestinians, and various refugee crises. Roughly half of the Jordanian population is Palestinian—more than two million of them refugees. Jordan, which had its borders drawn by European colonial powers after World War I, is a political haven. In addition to giving sanctuary to Palestinians, Jordan has also hosted large numbers of forced migrants from other countries in the Middle East, such as Lebanon during the 1975 to 1991 civil war, and Iraq since the 1991 Gulf War and after the 2003 removal of Saddam Hussein following the Anglo-American military intervention. And more than half a million Syrian refugees have crossed the border in the past few years. The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is a nice house in a rough neighborhood.

But was it safe? I texted a special agent in the FBI and former Marine who was stationed in Mogadishu during the 1990s. “It’s probably safer than Chicago,” he said. I thought about that for a while. Yes, I’d be brave enough to visit Chicago. The U.S. and Jordanian governments work well together—we provide aid and they provide stability in the Middle East. King Abdullah II is a 41st-generation direct descendant of the Prophet Mohammad who was educated in England and attended Princeton. He and his beautiful wife, the Palestinian-born Rania, are strong supporters of women’s rights, education, health care, and human rights. His father was the movie-star handsome King Hussein. His mother was British—the daughter of a high-ranking Army officer. His grandfather, King Abdullah I, worked with T.E. Lawrence during the Arab Revolt.

I said yes, and in the same breath, asked if we would be climbing in Wadi Rum. I’d pored over the descriptions by T.E. Lawrence in Seven Pillars of Wisdom and watched David Lean’s film Lawrence of Arabia so often that my daughters were speaking like Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif. Most of the movie was filmed in and around Rum Village—you can’t help but notice the sumptuously carved walls of rock. “Welcome to Wadi Rum!” says Sheikh Auda Abu Tayeh (played by Anthony Quinn). As the Bedouin troops move off across the wide, magnificent valleys of Rum and Um Ishrin, you are treated to a bird’s eye view of the East Face of Jebel Rum (you can see Goldfinger) and of the proud towers of Nassraniya.

We flew non-stop from New York to Amman, Jordan’s capital and a bustling city of about three million. You can catch a red-eye, settle in for 14 hours, arrive in time to have dinner, and be climbing the next day. Or spend a day exploring the ancient cities of Jerash, Petra (with the famous narrow canyon entrance that Indiana Jones rode through in The Last Crusade), and Madaba. There were barricades around our hotel, the first class Grand Hyatt Amman, and a scanner and X-ray security at the entrance. The Grand Hyatt was one of the places bombed in 2005, and now big hotels in the high-traffic tourist areas—Petra, the Dead Sea, Aqaba, and Amman—have security. We walked to dinner—a hip spot called Wild Jordan that’s run by the Royal Society for Conservation of Nature, with the goal of developing social and economic sustainability for Jordan’s nature reserves. King Abdullah, an avid sportsman—he scubas and skydives—is dedicated to protecting Jordan’s natural resources. My jitters dissipated as we passed by well-kept apartments, chic shops, and neighborhood gardens. It was exotic yet familiar. There were families, college kids, couples, and lots of single men of all ages talking or playing cards. Arabic is the official language, but English is taught from grade school onward.

“Will I be able to climb?” I asked again, trying not to sound pushy. Our tour guide, a clever man named Kamel Jayusi had spent a lot of time in Rum, but didn’t climb. Neither did our Jamaican-born Jordanian Tourism Board liaison, Janine Jervis. But she had a friend who did, and he planned to meet us around 9 p.m. back at the hotel. We sipped $20 mai tais in the hotel courtyard, sitting next to sheikhs wearing keffiyehs and immaculate white robes who were sipping tea and smoking fruit-flavored hookahs.

In walked Hakim. He’s a big guy, 6’ 2” or 6’ 3”, wearing jeans, sneakers, and a T-shirt, with soulful brown eyes and shoulder-length black hair tied back like a pirate. “I can’t take you climbing,” he said regretfully. He had to be in Petra. He’d been hired to climb on the ancient facades to check for cracks and loose rock. The National Geographic Society was sending a film crew. British climbing legend Joe Brown had helped with access work there in the 1960s, and this time Hakim could use a drill to establish some anchors. “I know one guide who can, though,” he said, “but he can take only two climbers.” Hakim’s words were met with silence—at least six other writers in the group wanted to climb, too.

Nearly single-handedly, he developed the first community of Middle East climbers.

In Lawrence of Arabia, Abu Tayeh describes himself as a “river to his people.” That’s a good description of Hakim. Nearly single-handedly, he has developed a community of Middle East climbers—the first ever. They’ve had two Wadi Rum climbing festivals and are working on route development on a limestone crag near Syria. There are climbers from Lebanon, United Arab Emirates, and Iraq. Hakim’s company, Tropical Desert Guiding Service, introduces people to hiking and canyoneering in Jordan, but he’s also taught a lot of people to climb for free.

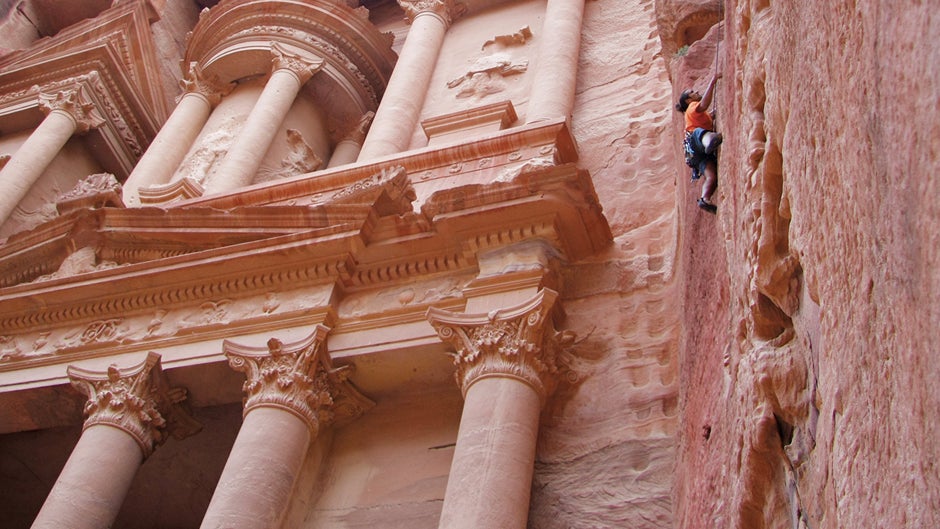

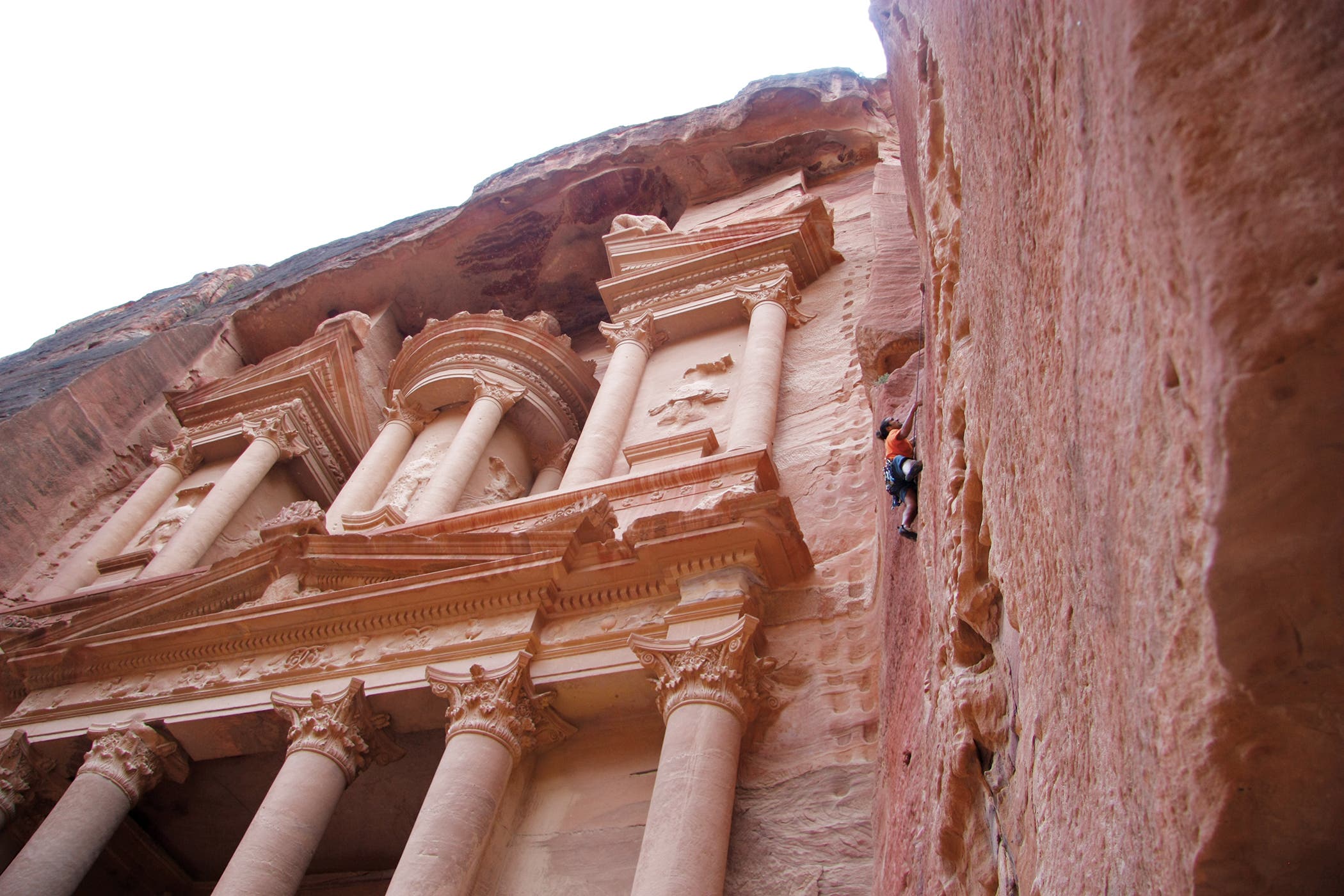

UNESCO had been alerted about a monstrous boulder that was coming loose from the base of a big wall in Petra. They called Tropical Desert and set about a massive project to reattach the rock. Then they turned their attention to the Siq (the impossibly narrow slot canyon with 100-meter-high walls that are the main entrance into Petra). Hakim helped to install more than 70 devices that would allow geologists and archaeologists to monitor rock movement. “It was a majestic feeling when they said they needed a device on the rock next to the famous Monastery and Treasury,” said Hakim. “Climbing there was one of the coolest things I’ve done in my life.”

To reach Wadi Rum, we drove along the King’s Highway—a pre-Biblical trade route between Egypt and Damascus. The road is roller coaster wild—big sweeping curves with one lane tight against the mountain, the other often looking out over thousands of feet of air. It traces the eastern rim of the dramatic Jordan Rift Valley and Wadi Mujib. Wadi (which translates into Canyon) Mujib is the Grand Canyon of the Middle East—it’s narrower than the real Grand Canyon, and in places, more than 3,000 feet deep as it slices a 150-mile path to the Dead Sea (at 1,400 feet below sea level). While Amman is densely populated, with big buildings, an extensive souk (open-air market), and antiquities that date back 20,000 years, the rest of the country is vast desert and mountains punctuated by amazingly fertile valleys and river beds. The canyoneering in this area is amazing—deep slot canyons with waterfalls and cascading pools, with oases of pink and oleander and palm.

As you near the edge of the escarpment of Ras en Naqab, big-featured mountains loom in the distance. There’s the pyramid-shaped peaks of the Barrah Mountains, and the porpoise-back arch of Jebel Rum. While prehistoric man lived in this area 200,000 years ago, and there are 2,000-year-old Nabatean ruins, this section of the Middle East wasn’t explored by Westerners until much later. The classic film, Lawrence of Arabia, introduced Wadi Rum to the Western world (it won seven Academy Awards in 1962). T.E. Lawrence (brilliantly played by Peter O’Toole), derided for his obsession over the Jordanian desert, explains, “It is clean.” And that’s one of its attractions, but he also called Wadi Rum “magnificent, vast, echoing, and godlike.” But it is also achingly beautiful, exotic, and strangely intriguing.

During WWI, T.E. Lawrence’s love affair with the Middle East (nurtured by the sensationalized reporting of American journalist Lowell Thomas) helped to bring the region to the world’s attention. His book Seven Pillars of Wisdom cemented the relationship—especially after it was made into an epic film in 1963. In 1984, British climbers Tony Howard, Di Taylor, Al Baker, and Mick Shaw watched the film. Howard was determined to climb there. He sent faxes to the Jordanian Ambassador in London, to the Tourism Ministry, and to King Hussein himself. Finally he got a reply. “We welcome you and your team to explore Wadi Rum for climbing and trekking.” And so it was written.

In 1984, there was only an old fort marking the old Saudi border, six houses given to the sheikhs by King Hussein—a magnanimous gesture and effort to bring them into the system—a couple of concrete block houses, maybe a dozen black goat-hair Bedouin tents, and a dusty shop piled high with a confusion of clothes, kitchen utensils, and vegetables. Howard remembers waking at dawn to see smoke curling up from the fires of the Bedouin tents as they roasted coffee beans before grinding them in large bell-like brass mortars. Then chimes rang out, welcoming people to the tent. There was a well near the fort, but no electricity. They were the only foreigners in the valley.

They were welcomed into Rum by the son of Sheikh Atieq and invited to his desert camp where they explained they were looking for climbs, and if the climbing were good, others might come. If they didn’t want that, Howard made it clear, the Brits would go. Sheikh Atieq agreed to the proposal, but as the Bedouin had climbed everything, why did the British need all that equipment when the mountains had all been climbed with nothing! Howard quickly discovered that his hosts were excellent mountaineers.

They lived and traveled with the Bedouin for two months, naming all the mountains, finding the Burdah Bridge, and climbing Jebel Rum by various Bedouin routes. The Bedouins proved sly sandbaggers—they’d point out routes and let the climbers have a go—sometimes not explaining that the seemingly straightforward route might require a bivy or two. The British team also established some new climbs, including a route to the baroque-shaped 1,580-meter summit of Jebel Kharazeh through splitter cracks, hidden chimneys, and solid, black patina rock, one of the few peaks not climbed by the Bedouin. Its Vanishing Pillar was staring them in the face every day, so it had to be climbed. The next year, Wilfried Colonna, a charismatic French guide who resembles a young Sean Connery, met Howard and Taylor in Morocco. Wilfried joined the Wadi Rum exploration team and became one of the region’s top advocates. In 1992, he helped to reintroduce Arabian horses back into Wadi Rum, as the population had dwindled after the Arab Revolt.

The village has grown since Howard first arrived—there are now three overspill villages out of Rum Valley, north of the Nature Reserve Visitor Center. There are two schools, one for the boys and one for the girls. Some of the local Bedouin population and guides worry that despite the fact that Wadi Rum was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011, a plan from the ASEZA (Aqaba SpecialEconomic Zone Authority) to approve 700 building plots adjacent to the village (opposite the Rest House) may impact the area’s unique geography, wilderness, and charm that earned it UNESCO designation in the first place. Debate about the potential impact that more houses (and cars) would have on the tranquil community and pristine nature of the landscape is fierce in town and around campfires.

The windy road takes you through the desert to a small rise and the Visitor Center. The view overlooking the Valley of Rum is grand—Ansel Adams would have gone wild. On either side there are a half-dozen miles of highly featured, colorful 1,500-foot cliffs. The shadows on the rock, framed by red sand and blue sky, captivate us. Several camels wander into view. By now, most of us have changed our ball caps for traditional scarves. From here, you can catch a bus into Rum Village, or better yet, get picked up by your guide. Chances are you’ll ride on cushioned seats in the bed of a pickup, or you could go by camel or horseback; either way, you’ll have a 360-degree view of the desert.

Hakim’s friend in Wadi Rum is Mohammad Hammad, arguably the best Bedouin climber around. His father, Hammad, was in the Jordanian military and pioneered many of the first technical routes on the cliffs. Hammad’s Route to the summit of 1,754-meter Jebel Rum, is one of the classics. The route starts out on low-angled sandstone steps and follows a 5.9 crack, with face climbing through huecos reminiscent of Smith Rock’s Five Gallon Buckets. You can make it to the summit and back in a day, but there are some sweet places to camp on the summit.

By his 10th birthday, Mohammad was climbing with his father on ibex-hunting parties in the mountains. By 16, he and his friend Omar Aoudah had acquired a collection of climbing gear given as thank-you gifts in return for providing transportation across the desert. There were no specialized shops in Jordan, and the boys relied on visiting European climbers and guides to learn how to belay and build anchors. He’s climbed on the limestone north of Amman with Colonna—the two set up the first bolted line of Ajloun limestone (at Sami’s Cliff)—as well as on the conglomerates in the south, which still haven’t been repeated.

While the idea of being a climbing guide is widely accepted in Jordan today, there are only a handful who guide technical routes, and only three real professional mountain guides in Wadi Rum (as recognized by other professional guiding associations from abroad).

Climbing has grown in popularity in Jordan. Climbat, the climbing gym in Amman and the biggest in the Middle East, has about 5,000 members. The gym is first-class—it hosted a World Cup in 2011. There are now several bolted limestone crags north of Amman. About 500 climbers visit Wadi Rum each year for technical climbing and the Bedouin routes. The traditional Bedouin routes are more about mountaineering and alpinism than pure technical climbing, even if some parts of Wadi Rum cliffs look like sport climbing crags. There are still only a few fully bolted climbs. Most of the climbing here is about trad: nuts, cams, wedged knots, and threads on soft sandstone.

On my second trip, this time with Backpacker magazine, I flew in early to hang out with some of the local climbers in Amman. Mai Turki picked me up from the airport; she’s an active part of the local climbing community. My ride back to the airport was with Safa Muhi, the first sponsored female climber from Iraq. I asked her what it was like being a female climber in a Muslim country. “I grew up in Iraq,” she said. “When you live your life expecting death any second like kids waiting for snow on Christmas, and then you get the chance to live a normal life—one when you kiss your mum goodbye as you leave the house because it’s customary, not because you might go out that door and not come back alive—a life where you get to feel bored once in a while, it makes you grab every chance you get to feel alive and never miss a moment because the idea of dying any second still hunts you down. I love climbing; I never let myself feel bored because it’s shameful to feel that way after I was given a better life to live.” She refers to Hakim as the godfather of climbing in Jordan, and Wilfried as the great-godfather. Both Mai and Safa are Muslim, but neither wears a headscarf (however, women can and do climb while wearing sleek-fitting hijabs). Safa comes from a traditional Iraqi family. She and her sisters fled to Jordan during the war, but her father and brothers remained in Baghdad. Her father originally discouraged climbing; he worried she’d get hurt. He suggested that it was forbidden in Islam. Her mother calmly replied that Khadejeh, the wife of Prophet Mohammad, used to climb Jabal al-Noor (mountain of the light) to bring him water and food. I asked Mohammad Hammad about the proliferation of female climbers in Jordan. “Many of the visiting European climbers in Rum are women,” he said. “And there are girls from the North (Amman) who climb—but none from the traditional South.” But he guilelessly told me, “Some shepherd girls are pushing very far in terms of Bedouin routes with their goats.” Amy and I plan to return to Rum and see if we can get the girls in harnesses. I asked him if he’d teach his daughter to climb, and he said of course, but that she’d be exposed to many sports and will make her own choices.

You can walk to hundreds of climbs from Rum Village, and some of the most classic are just a few minutes to an easy hour away. One famous is Jihad (also known as La Guerre Sainte), a wild multi-pitch sport route located on the eastern side of Jebel Um Ishrin, east of Rum Village. This 400-meter desert beast was bolted by French climber Arnaud Petit and graded at 7b+ (5.12c). The first few pitches are very exposed; bolts can be four to six meters apart, but the sandstone is solid there. Near the third pitch is some crimpy climbing, but farther up, the rock gets sketchier, and with such distance between bolts, you want to move cautiously to avoid a 12-meter fall.

On my second trip, I did the four-day hike from the Feynan Eco Lodge (Dana Biosphere Reserve) to Petra. I had a few days in Wadi Rum and “discovered” the quintessential rest day. From the village, you can retrace T.E. Lawrence’s footsteps across the desert while scouting the best climbing walls. The dramatic landscape has narrow gorges, natural arches, towering cliffs, ramps, and caves that shelter more than 25,000 documented rock carvings, with 20,000 inscriptions that trace the evolution of human thought and the early development of the alphabet. The area is 720 square kilometers—nearly 300 square miles. We walked from where the Nabateans settled in 300 B.C.; this was the first place olive trees were domesticated. The village is on the site of an important Nabatean trading route between Arabia and Syria. We hiked about a mile to Lawrence Springs, where T.E. Lawrence was hiding during World War I. Most of the scenes in Lawrence of Arabia were shot there in 1963. Then, across a couple of miles of unbroken desert—the heart of the reserve and then to Al-Khaz’ali Canyon—where there’s a beautiful slot canyon to explore.

Wadi Rum strictly follows the traditional climbing ethos, and even the use of chalk is frowned upon by locals. The bold routes of Austrian clean-climbing legend Albert Precht have by far the purest ethic and present the greatest challenge—though not many climbers attempt the necky runouts. Only three bolts were used to complete the 10-pitch, 350-foot Pillar of Wisdom, first climbed by Colonna, Howard, and Taylor in 1986. Subsequently, Colonna and the Jordanian Tourism Board have worked to put safety rappels on popular descents. And outside the Protected Area, sport-specific crags are continually being developed. There are now some superb routes on Nassraniya in particular.

Rum rock is sandstone, mostly good but some not. It can go from really hard to the consistency of a frozen snow cone. And as always with adventure climbing, it’s a matter of learning to read and respect the rock. Like in Indian Creek, the Dolomites, the Black Canyon, and Zion—the color of the rock can tell you a lot. Route-finding on Bedouin routes is almost always tricky, and descents are rarely obvious. The general rule for Bedouin routes, as Colonna told me, is to avoid difficulties if possible and think like a Bedouin, who is thinking like an ibex. And ibexes are brilliant climbers. Newer routes do generally follow the obvious lines and crack systems. Wadi Rum has some bolted sandstone walls (with glue-in rings preferred over bolts), and there’s also some easier multi-pitch stuff where people hone their trad skills before launching up the big stuff. The commitment level changes quickly, and the nature of the sandstone forces you at first to climb one or two grades lower than usual. Even at a higher level.

Beneath the Rum sandstone there is a plinth of granite, which offers excellent bouldering and a few 20-meter climbs. Outside Rum, there are the granite and basalt mountains of Aqaba, striated with igneous intrusions. Only two or three scrambles have been done there—but the potential is obvious. To the north, the sandstone appears at its colorful best in Petra. North again there is some conglomerate near Dana. And as you head farther north, there are some sandstone canyons with basalt intrusions. Northward from here, the rock is mostly limestone, providing some trad climbs and many sport climbs, particularly at Al Ayoun, north of Ajloun Castle.

Considering that Rum is a serious mountain area, there have actually been very few accidents in the past 30 years. The worst was undoubtedly the death of three French climbers, two women and a man, this spring on Goldfinger, the route I climbed with Amy and Mohammad. They were experienced climbers, but reputedly didn’t have sandstone experience. They had threaded a bridge for an anchor on the third (crux) pitch; two were clipped in, and the leader fell. Local climbers report that their belay wasn’t the standard one—but off to the side of the traditional route. They fell more than 200 meters. The next week, Colonna and Howard helped the locals with the body recovery of a young Amman photographer who’d fallen in one of the canyons. It was a grim week.

With so much political turmoil nearby, Jordan is the anchor of the climbing community.

There are more than 200 routes listed in the guidebook Howard wrote in 1994, and a lot of development since. There are multi-pitch routes from 5.8 to 5.13, and lots of 5.10s and 11s. Expect routes from five to 25 or 30 pitches that require significant commitment and route-finding. Colonna is writing a new book; it should be out by this winter. Climbing in Jordan is still wilderness climbing, but it is poised as the next adventure playground. With so much of the Middle East closed to climbing due to political turmoil, Jordan has become the anchor of the climbing community. With the development of a strong local climbing community in the past year, a pro-Western culture, and increased media attention, Wadi Rum is moving from an exotic dream to a must-do on every trad climber’s bucket list.

One of the harder climbs in Wadi Rum is the bolted Glory, a five-pitch sport route put up by Ofer Blutrich, a very strong Israeli climber. It goes at 8a+ (5.13c) and sports a hard, spectacular, and ultra-technical third crux pitch. The rest of the pitches (10a, 12a, 12b, 12a, respectively) are all beautiful, technical friction climbing on steep, dark rock. This spring, Klemen Becan, a Slovenian climber, did the first 8b+ (5.14a) of Wadi Rum. It might be the least-steep 8b+ in the world—even less than vertical—a testament to the technical level of the testpiece.

Mohammad and Wilfried came to visit at our campsite. Rather than the group desert camp where there are big, individual sleeping tents, bathrooms, and even showers, this time we were carrying our own tents and stretching out under the stars on the still-warm desert sand. I’d brought a new rope for Mohammad and climbing shoes for them both—it is still nearly impossible to find technical climbing gear in Jordan. My group had made chocolate mousse for dessert, which Mohammad and Wilfried loved. Wilfried accepted a glass of wine, and we spent the next couple of hours talking about climbing—a universal language. Sitting around the campfire, shooting stars overhead, we spoke about religion and politics, culture, and climbing. We sipped outrageously sweet tea that Shuayb Twassi, a terrific guide from Petra, had prepared on a nest of three rocks. The next day, I went camel riding—something I’d do everyday if I lived there. I took the reins from a young boy who was helping his father and uncles. I’m comfortable on a camel, and I smiled as it sprinted off across the desert, threatening to toss me off like a scene in Lawrence of Arabia. I grasped the reigns more tightly. Looking down, I saw they’d been made of an old climbing rope.

For more info, check out Wadi Rum Climbing Resources.

Bedouin Tick List

Most of these Wadi Rum routes can’t be found online or in guidebooks and are appearing in Western climbing media for the first time. By Wilfried Colonna.

Traverses/Summits

North-South Traverse of Jebel Rum (5.5)

This 5,754-foot route is generally done in two days with a bivouac on the mountain. It’s not difficult, but sustained and long. If you don’t have prior experience at Jebel Rum, you must visit with a guide. Excellent route-finding skills and a gentle touch will deliver one of the most beautiful experiences on “The Lord” of Jordanian sandstone summits, the Jebel Rum. For experienced mountaineers only! There is nothing harder than low fifth class; just tricky scrambling, walking, and one 75-foot rappel. This can also be done from south to north (and thus without any rappel).

Jebel Khazali (5.8)

Tag the summit of Jebel Khazali (4,658 feet) by ascending Al Lassik (5.8) east to northeast, then turn east to descend Sabbah’s Route. This generally done-in-a-day affair has many short class three and four passages. The crux pitch is fun 5.8. An amazing, doable adventure on one of the most attractive mountains in Wadi Rum.

North-South Crossing of Jebel Geder (5.4)

If you want a rest day activity or a short itinerary to take in some scenery, tackle the 4,101-foot dome of Jebel Geder crossing from north to south. It starts with low fifth class climbing, followed by a fairly long walk on the domes toward a remote, massive summit. Winding around hanging terraces in the middle of a wall on the descent provides the most intricate introduction to the area’s crazy topography. “No way it goes here! Wait, yes, here it is!” It takes one or two 45-foot rappels.

Moderates

The Hadj (5.8+)

South Face of Jebel Sweibit’s South Summit, 7 pitches

This is one of the most southern climbs in the region, a 45-minute drive from Rum Village and not far from the Saudi border. A true area classic on a beautiful summit. If you only have time for one route of this difficulty, this is the one! It’s a varied route, combining steep cracks at the start and beautifully carved slabs in the second half. It’s all on excellent rock after the second pitch (however, use caution with the loose blocks on the middle terrace), and it has excellent protection. The exposure and body positions make it feel amazingly more difficult than it actually is! The descent is an easy alpine walk-off on the opposite side, down to Ghôrm Jarish canyon. Get there early: It only gets morning shade.

Goldfinger (5.9)

East Face of Jebel Rum’s East Dome, 4 pitches

A great introductory route to the area on the small central tower at the base of the Main East Face of Jebel Rum, just above Rum Village. The two-pitch “approach” to the main finger crack is on poor rock but easy (5.4). Then it moves onto 115 feet of perfect sandstone with great protection (5.9). The top pitch is a bit sandy (5.9+). Descend by four rappels on glue-in rings with chains to the left of the tower along the route called Troubadour (5.10b).

Mohamed Bouazizi (5.9)

Um Rashid North, 5 pitches

A fairly easy route, with only one hard and steep passage in the middle of a black wall, but it’s well-protected with wires and small cams. The rest is 5.6 max on low-angle rock, and ends in local “alpine terrain,” which allows you to scramble easily to the summit via the west side. Then get back to the sands by a beautiful Bedouin path that travels southeast into the hidden valley behind. A harder variation climbs up the obvious corner left of the black wall.

Giraffe Wwithout Niqab (5.9+)

East Face of Jebel Geder’s South Summit, 5 pitches

A short afternoon route (with shade!) on the beautiful south part of the massif. It’s on the way to The Hadj. The rock is fairly soft on the upper part of this obvious corner, but solid on the top crux section. Use caution during the required ledge scramble that links the two parts of the route. It’s full of loose boulders. A perfect taste of the local “soft-touch” climbing style! The route has good protection; rack smaller wires for the final crux wall, which looks harder than it is. To descend, join the Jebel Geder Crossing itinerary on the way down through the final red sandstone flank.

The Beauty (5.10a)

West Face of Jebel Um Ejil, 5 pitches

An hour walk from Rum Village, this, uh, beauty is the most-climbed route in the valley! It has all the ingredients to make it a perfect half-day adventure—a sumptuous approach in the depths of the mountain, excellent rock, and each pitch with its own character. Laybacks, stemming, technical slabs, and a surprising finish on the “banana crack” where a No. 5 cam and at least one No. 4 are crucial for protection. The first ascensionists used a single No. 3.5, just in the last five meters. The very top of the mountain is worth a visit (optional scramble after the last pitch). Descend along the route. All belays and rappels are on glue-in rings. You’ll need a complete set of cams and a handful of medium to small wires. For the rest of the day, try the neighboring route, Alan and His Perverse Frog (5.10b/c).

Merlin’s Wand (5.10b)

Barrah Canyon, 5 pitches

A magic line that spends nearly all day in the shade. A continuously straight crack in excellent, strong rock on a shady wall of Siq Barrah. Only the first 50 meters are crack climbing. The upper part offers fine technical moves on perfectly clean and steep sculptured sandstone, with gouttes d’eau (translation: water drops) limestone-like curved holds. You can drive right to the route. Belay from the footboard of the jeep! Descend by four rappels along the route.

The Pillar of Wisdom (5.10b)

East Face of Jebel Rum, 15 pitches

It has an irresistible appeal to the heart of any climber. It was one of the first lines discovered by the first Anglo-French to climb here and quickly became a classic at the intermediate level, with a spectacular crux in the last few meters. The rock is generally soft but solid enough to offer fine and varied climbing with good protection. Descend by Hammad’s Route, the regular way from Jebel Rum summit toward Rum Village, with some down-scrambling and seven or eight rappels.

The Star of Abu Judeidah (5.10d)

Barrah Canyon, 8 pitches

Local climbers just call this route, a 40-minute drive from Rum or Diseh villages, “Star.” Some see it as one of the world’s most iconic sandstone classics. And it’s certainly one of the best climbs in Wadi Rum! Varied, sustained, and in very beautiful surroundings in the middle of a canyon where climbs are lined up like a parade. With the exception of a few meters on pitch three, the dark sandstone is just excellent. There is also one short, well-protected section of offwidth on pitch six. Descend along the route, which gets afternoon shade.

Stout Routes

Muezzin (5.11a)

East Pillar of North Tower, 15 pitches

Climb up the sand dune to reach the start of this exceptional climb up an impossible-looking pillar. It’s fascinating for its committing character, entirely on trad protection without a piece of metal in sight. This is the calling card of the famous Austrian team who developed it. No bolts, never! Exactly the opposite character of Jihad (a bolted 5.12c). It’s definitely a “big” climb and for competent parties only. Nothing technically harder than 5.10d, but the crux pitch is very sustained, pushing the grade to 5.11a. Plan for a seven- to nine-hour climb. Descend on the rappels of Jihad.

Raid Mit the Camel (5.11c/d)

East Face of Jebel Rum’s East Dome,1 2 to 14 pitches

This is one of the climbs that has opened the way to a new trend in the valley, keeping a certain character of trad climbing but with adequate bolting in some places. Mixed, as you call it in the States. Raid is unanimously acclaimed by the climbers who enjoy this comfortable compromise. It is one of the finest routes of its level in Wadi Rum. The first four pitches are very nice and sustained. Descent is possible by 10 rappels down the route, but much better to follow the raps of Rock Empire. Otherwise, from the East Dome summit, down Eye of Allah and the abseils of I.B.M.

Towering inferno (5.12a/b)

East Face of Jebel Rum’s East Dome, 12 to 13 pitches

Elegant climbing along a very direct system of superficial cracks and open corners. Very popular for the first four pitches, constituting the Shortclimb Inferno (5.10b). The rock is mostly perfect, albeit with some short softer parts, especially in the upper pitches where curious veneers can leave one doubtful. One can also opt for the less radical method of the pioneers: aid climbing. Knifeblades and angle pitons of various lengths were used at the time. A handful of pins should be enough, along with the essential micro-cams and numerous small wires. Some gear has been left in place (pins), besides the excellent peg-bolted and glue-in belays on the lower part. Confidence in small wire protection is the key to success. Descend from the “fourth floor” by rappels, or if you choose to summit, descend via Eye of Allah’s or on the new rap stations on I.B.M.

Providential Al’uzza (5.12D or 5.11C A0)

West Face of Jebel Khazali, 10 pitches

One of the hidden gems of Wadi Rum, since it’s concealed in a little side canyon at the end of the main West Face of Jebel Khazali. An exceptional and intimidating line up a smooth dihedral. Steep and strenuous crack climbing brings the pump up high on the dihedral. Escape the corner by a bolted traverse (goes free at 12d, otherwise A0) to the right arête of the flank, then continue up more corners to the top. All belays in place. Descend by rappelling down the route or via Martha Steps on the west side.

La Guerre Saint (5.12b)

East Face of Nassraniya North Tower, 12 pitches

The most well-known climb in Wadi Rum and for good reason. Not because it is entirely protected by glue-in bolts. Rather that prior to its establishment, it was considered unclimbable. That climbers found an ongoing line of holds through the headwall is a miracle! The already-solid rock has been cleaned even more by numerous parties throughout the years. Compared to any other trad routes around, Jihad (the route’s English translation) exudes a soft atmosphere of “quiet holidays” because of its well-protected sport climbing character. A rope, quickdraws, and slings—that’s all you need! Descend by rappelling on the route itself.

Tira Il Diavolo per la Coda (5.12d/5.13a)

West Face of Jebel Barrah North, 12 pitches

The ragni of Italy certainly does not mean much for the American climber. But remember Riccardo Cassin was the most famous member of that group of “spiders.” They still exist today, and some of them have been active all over the world, and of course, in Wadi Rum as well. The route (which translates to “pulling the devil’s tail”) goes from a fully bolted option on the first pitch (5.12d) to traditional crack climbing higher up. It’s very steep and sustained, but very well-protected and on nearly perfect rock. It’s part of a new generation of routes, where difficulty doesn’t mean ultimate commitment, with bolts where they need to be, and trad protection where it is obviously safe enough. A wonderful gift from the ragni, who developed it. Descend by rappelling the route.

Geschenk gottes (5.10d A1)

West Face of Um Ishrin Tower, 23 pitches

This ranks as one of the greatest climbs of Wadi Rum’s big walls. Makhman Canyon, not too far from the village, is one of the main sanctuaries for such powerful challenges. Very long and sustained, this route offers a serious undertaking with a certainly unavoidable bivouac. It boasts some of the best rock quality in Wadi Rum. All pins, fixed slings, and knots are in place, though the grading has not been confirmed yet. Halfway up, the route meets the extraordinary and fairly easy line of Rund um die Welt (5.9), which comes from the east side of the mountain by following the upper hanging part of Makhman Canyon. I tell you, here it’s not just about climbing, it’s about penetrating the deepest mystery of the mountains! Descend along the route by rappelling and down-scrambling.

Jolly Joker (5.11a)

West Face of Nassraniya North Tower, 20 to 22 pitches

It’s a journey, not just a climb. If you’re looking for something new and exotic, go for it! Another great line on a very big wall with a really serious atmosphere—and sometimes just with a good-natured feeling. Overall, it’s quite strenuous despite some easier sections. Be prepared for exposed passages, especially for the following climber, due to numerous traverses. The quality of the rock is good. Slings and pins are in place. For competent parties only. It has been climbed in less than four hours, but you should plan on at least twice that.

Au Gres Du Vent (5.12b or 5.11b A1)

West Face of Nassraniya North Tower, 18 pitches

A 30-minute hike from Rum Village in morning shade. Its name is a French pun, meaning “with the wind.” It was pioneered by two French climbers from the Pyrenees mountain range between France and Spain. It’s a very beautiful and powerful climb of great caliber, and an incredible contribution to the world of climbing. It’s serious and sustained with some exposed passages in the middle of a huge wall that offers nearly every quality of the local baroque sandstone. Some specific gear is required: two large skyhooks, hammer, and a few pins, as well as a hand drill, in case of some damaged pins or bolts, and numerous slings. Descend by Hikers Road, 10 minutes away from the finish, or by the more straightforward rappels of Jihad on the east side after a summit hike of 35 to 40 minutes. There are some cairns to locate the start of the rappels.

Jordan Rock Climbing Beta

You can climb year-round in Wadi Rum, but the real season is late September through mid-November and March through May. There are flights to Amman from Chicago, New York and Detroit (flying through Montreal) on Royal Jordanian Airlines. You can also fly from any airline through Europe and catch a short flight to Amman. There are buses available at the Queen Alia Airport, but the best bet is to hire a driver via a guide service (hire Mohammad Hammad himself at bedouinguides.com).

Nancy Prichard-Bouchard, Ph.D., is a longtime climber, writer, and risk-management expert. She has written about climbing, gear, and adventure travel for more than two decades and has established the first-ever Middle East Climbing Team (sponsored by Five Ten). She thanks Mohammad Hammad, Hakim Tamimi-Marino, Safa Muhi, Mai Turki, Tony Howard, Wilfried Colonna, Bassam Kubba, Sushi Firas, Elad Omer, Amy Jurries, and Shuayb Twaissi for their contributions.