A Perfect Mediterranean Climbing Feast in Sardinia

"Sardinia Rock Climbing Sport Climbing"

At the parking area above a quarter-moon cove, near the seaside resort and climbing hub of Cala Gonone, beachgoers unloaded coolers and umbrellas from their cars. A tour guide ordered his charges to line up for the stairs down to the beach. White limestone buttresses lined the coast and the canyon heading inland from the sea. But where were those olive-skinned Italian gods and goddesses I’d seen in photos of Sardinian climbing, stretching between pockets on massive overhangs? The few climbers in sight dangled from vertical 5.8 and 5.9 routes by the sea.

Sardinia was the first of the Mediterranean “sun rock” destinations, where vacationing Europeans headed south to escape rainy northern cities. Climbing here dates back more than 70 years, and the first sport routes appeared in the 1990s. But these days many climbers flock to newer Mediterranean hot spots like Kalymnos in Greece, Mallorca in Spain, and Sicily in Italy.

It’s not that Sardinia lacks impressive climbing. Friends were quick to recommend the 470-foot Aguglia di Goloritzé spire, the five-pitch sea cliffs by Cala Gonone’s Millennium Cave, and the roofs and overhangs of Isili. The famous Hotel Supramonte, a 10-pitch 5.13d that’s one of Italy’s hardest long routes, rises up just a few miles from Cala Gonone. But even though we arrived in mid-May during perfect climbing weather, sunbathers far outnumbered craggers.

Sardinia’s casual, uncrowded vibe suited our team of five just fine. For this group of old friends, eating, drinking, and relaxing in a semi-exotic spot were at least as important as sending, and as we beelined toward those easy sport climbs by the beach, I knew we’d come to the right place. With its varied crags and easily accessible boating and hiking, a trip to Sardinia is like a traditional Italian dinner, with many courses at the same setting. And as I was about to learn, you can still stuff yourself with many small helpings.

Antipasto

Swaying blooms of yellow ginestra bushes lined the road as we drove 90 minutes from the airport at Olbia to Cala Gonone. A modern highway traverses Sardinia, an island the size of New Hampshire, but the smaller roads twist through the mountainous terrain like a Coney Island roller coaster. We hadn’t seen the sea for an hour when a signpost for Cala Gonone pointed through a tunnel in a mountain. On the far side, we emerged into a vast bowl of limestone-studded hills, the ocean stretching across the horizon from rim to rim. A narrow road stair-stepped down tornanti hairpins toward the orange tile roofs of the village.

Nearby Cala Fuili was the perfect climbing appetizer. A shore road led a couple of miles from town to a long set of stairs down to a cobbled beach. On the far side rose a 60-foot prow of limestone with 5.8 to 5.10 routes, the best of which was Spigolo Fuili (5.9), where plates of firm but polished limestone and shallow cracks led up the left side of an arête. Facing the rock, it was easy to forget where you were. But then you’d glance over your shoulder and be startled by the sea, less than 50 yards away, shining the dazzling blue of dreams and Disney cartoons.

At lunchtime we hiked up the twisting stony bed of the Codula Fuili, the canyon leading inland from the sea. Hot sun bounced off the white rock, but in early afternoon, a cooling sea breeze began flowing up the canyon. The calls of unfamiliar songbirds echoed from cliff to cliff, and brilliantly colored lizards scurried over rocks. The walls of Codula Fuili are incised with caves that hold some of Cala Gonone’s hardest sport climbs, but we aimed for a short vertical wall tucked in the bushes, where the footholds were sharper and grippier than they had been by the beach.

“Now this is the kind of rock I like,” Robin said after sending a tricky 5.10a face. “The kind that bites into your shoes like it has teeth.”

On the way back through town, we stopped at a small deli and stocked up on fresh Castelvetrano olives and marinated polpo (octopus) for antipasti. We set up a table on the patio outside the three-bedroom apartment we had rented and sipped cocktails, watching the fading sunlight play over the sea. Appetite whetted? Sì!

Primo Piatto

We woke to the sound of patio furniture crashing outside the house. A cold wind, the maestrale, had arrived overnight. A woman in town told us it would last one, three, or six days. We wondered if we would find a place warm enough to climb.

We found the answer at Biddiriscottai, a seaside cave that promised shelter from the wind and a mix of easy and testy routes. From a dead-end road just north of the port, a path led along tidal shelves where sheets of salt had encrusted potholes in the rock. Painted boulders warned “Nudi” and “Naturisti,” but when we climbed up a broad sand dune to the cave, we found only a lone bearded Sardinian who had camped there overnight—he looked on curiously as we geared up and then moved on.

Biddiriscottai’s centerpiece is a broad, flat-ceiling cave about 50 feet high. A line of very fun 5.8 to 5.11 routes ascends the near-vertical wall in back, linking giant pockets and curving flowstone and tufas. Much harder routes lead out the ceiling—some of these require downclimbing the slanting roof to reach the lip. Belayers stand in deep, orange sand. It’s like a giant playground.

It was easy to find the most popular routes—they were the ones with slippery, polished limestone and shiny, newer bolts. Rebolting is a constant chore on the seaside climbs of Sardinia, where the salty, humid sea air corrodes fixed protection. Often, however, climbers choose to develop new routes or entire new crags rather than fix up the old ones—our guidebook showed at least three entire crags developed in the past three years. Less popular routes exhibited rusty relics of bolts and pitons or tattered slings threaded through holes, like an A4 pitch on El Cap.

Dave’s second route of the day ascended a well-worn wall of slippery flowstone on the right side of the cave. The climbing wasn’t difficult, but the finish required surmounting a short overhang on jugs to reach a little cave. To clip the anchors, you had to reach back behind you to the outer wall. The cave was much too small for standing up, and as Dave contorted into various squats and tried to make the clip without toppling out of the cave, his curses rained down to the beach. I showed the guidebook to Karen, his wife, who was belaying. “Dave!” she laughed. “The route is Fuck.”

“You don’t have to tell me!”

The steeper walls of the cave held 5.10s to 5.12s, including a route called Paolino (5.10c) that had the biggest holds you’ll ever find on a 5.10+. Farther up the coast are many new routes, including the enormous Millennium Cave with multi-pitch lines and routes up to 5.14c.

But we were ready for some cold Ichnusa beers. (Ichnusa, an old name for Sardinia, is derived from the Greek word for “foot”—the island is supposed to resemble the shape of a footprint.) On the menu that night was pizza, the staple of cost-conscious travelers in Italy—a 12-inch thin-crust pizza costs about half as much as a single main course in Cala Gonone’s restaurants. I ordered a pie topped with bottarga, an ingredient I’d never heard of. This turned out to be dried, ground mullet roe—a fact I was happy to learn after I’d wolfed down the delicious pie.

Contorno

Half days and rest days factored largely in our team’s plans. It was a climbing vacation afterall. One day we visited Ispignoli, a stunning cave that you enter at the top, then wind downward along steep staircases around a 125-foot stalagmite, the second tallest in the world. I nearly fell off the stairs scoping the column for climbing lines. At Tíscali we hiked about an hour through a cedar forest and limestone gorge to reach prehistoric ruins that line the sides of a huge collapsed cave, like an upside-down bowl of limestone. Another cool hike goes into the narrow Gola di Gorrupu gorge, home of Hotel Supramonte and other multi-pitch testpieces—some of the best limestone in the area. Yellow and orange euphorbia bushes filled the hillsides, giving the landscape the feeling of autumn, even though it was still spring.

Outside of Cala Gonone, the locals spoke English haltingly, if at all, and food and church replaced fashion and fun at the center of village life. We saw no Americans during our eight-day trip, and the owner of the Lemon House, a climber’s guesthouse farther south in Sardinia, said North Americans make up only six percent of his clientele. We’d just spent a week in Rome unable to avoid American accents, but the Sards couldn’t recognize our origin—they pegged us as British or even French.

Like the contorni, or side dishes, that accompany an Italian dinner’s main course, rest days added welcome variety and flavor. But the Cala Gonone guidebook lists 25 separate climbing areas, most with multiple cliffs and sectors, within about a 15-minute drive of our apartment, and I craved more.

One morning I walked up to La Poltrona, the most prominent cliff in Cala Gonone and one of the most popular. This 500-foot amphitheater of slabs, visible from anywhere in town, holds more than 80 routes, up to six pitches high. But the maestrale had passed, and I wasn’t attracted to slabbing in hot sun. Instead we drove toward Bonacòa, a fin of limestone high over the sea, where the access road was so narrow and exposed that one passenger preferred to walk. All day the bells of sheep and goats browsing on nearby shrubs mingled with the jangle of our carabiners.

Late one afternoon I drove with Robin and Chris, my wife, back through the tunnel to Dorgali, the nearest large town, and we found our way to the scruffy S’Atta Ruja crag. The area felt pleasantly untraveled, with crisp holds. Wildflowers and rosemary protruded from pockets. A step into the bushes yielded the aroma of crushed fennel. Each new climb made us hungry for more.

Secondo Piatto

We were ready for the main course: the famous Cala Luna beachside crags, about two miles south of Cala Fuili along the coast. You can walk to the beach by a rugged trail (1.5 hours), but our crew included four longtime sailors, and there was no doubt that we’d be going by boat. After a short round of negotiation by the docks—we skipped the guy with the sailor cap who shouted “God bless America!” and whistled “Yankee Doodle” when I walked by—we piled our gear into a small boat with an outboard motor and cast off across the Gulf of Orosei.

Robin took the wheel as we sped over small waves along the coast. Orange and gray cliffs, mostly unclimbed, plunged hundreds of feet into the sea. The Sardinian coastline is protected from new home or resort construction, and this area is traversed only by the Selvaggio Blu, a half-hiking/half-mountaineering coastal route that takes up to a week to travel. After 45 minutes we turned toward Cala Goloritzé, said to be one of Europe’s most beautiful beaches. Boats are only allowed to land at certain spots, so we hovered offshore to gape at the Aguglia di Goloritzé, Sardinia’s most famous landmark—about 10 three- to five-pitch routes, from 5.10 to 5.12, ascend the needle. Our group had neither the time nor the motivation for these challenges, and I stared wistfully back at the spire as Robin wheeled the boat around and headed back up the coast toward Cala Luna.

A steel pier lets you unload gear at the south end of the beach, but the rules require you to leave boats offshore. Dave took the helm, anchored the boat a few hundred yards away, and dove in for a frigid swim—the water here isn’t warm enough for comfortable swimming until midsummer. Cala Luna’s best easy routes are left of the beach: face climbs with small, incut holds, starting from a little perch about 200 feet above the sea. We ticked them all as fishing and tourist boats cruised by and seabirds wheeled in the breeze. You could easily imagine 50 shades of blue as the sun and shadow played over the sea.

Most of the team decided it was now beach time, but Chris and I were still keen to climb, so we headed to the row of shallow caves that line the north end of the beach, like the arched galleries of a fortress. I chose a well-chalked route on the nearest cliff, said to be 5.11. As in many areas, the easiest routes here aren’t necessarily the best. (The routes in this sector are mostly 5.12 and 5.13.) The first bolt wiggled in its hole, and it was backing up a relic so rusted I could barely fit a biner into the hanger. The initial footholds were so polished and slippery that I greased off the pedestal at the base before grabbing the first handhold and tumbled backward into the sand, next to a blanket full of sunbathers. Where was that cold maestrale wind when you needed it? Chris braced my legs so I could clip both the derelict bolts and start the route, and then I struggled up the 50-foot cliff, zigzagging to clip bolts along three different routes and creating a sea anchor of rope drag. An old woman shouted into her cell phone as I climbed. I wondered if she was narrating the fiasco in front of her.

I belayed Chris up the route—“slippery but fun!”—and then we headed back toward the dock past a semi-wild pig aggressively begging for snacks from tourists. We had one more stop before returning the boat to Cala Gonone. Halfway back to town, the mouths of two caves faced the sea. Nosing our boat carefully inside the left cave, we found a series of piers—it looked like the villain’s secret lair in a James Bond film. This was Bue Marino, a cave system that extends far into the coastal limestone. In late afternoon a guide opened a steel gate, and we followed her along a catwalk for more than a kilometer, passing Neolithic petroglyphs and the water-filled Hall of Mirrors to reach Seal Beach, where the endangered Mediterranean monk seal used to come to raise pups. (Bue Marino is derived from the Sard words for “sea ox.”) You also can hike to Bue Marino from Cala Fuili, following a rugged path and ladders for about 45 minutes.

That night we had reservations at the Agriturismo Nuraghe Mannu, a farm-to-table establishment along a single-track road that traverses the hillside below Bonacòa, near the ruins of structures built by prehistoric Nuragic people as much as 3,500 years ago. The secondo piatto was goat ribs in a dark, savory sauce. We tried not to think of the little guys we’d heard at the nearby crag as we washed down the meat with Cannonau, the local red wine.

Digestivo

Chris and I wanted to sneak in a few pitches before heading to the airport, so we drove twisting gravel roads to Buchi Arta, a recently developed cliff band stacked with 5.10 and 5.11 routes—one guidebook said it was among Italy’s best new cliffs. But a construction crew had blocked the road, sending us back the way we came. It felt like we were leaving before we’d really gotten started. We never saw some of Cala Gonone’s best crags for moderate climbers, including Il Budinetto and Margheddie, let alone Goloritzé and the other harder or longer climbs. There was just too much to do. Yet my fingers throbbed and my limbs felt limp, and secretly I was glad we couldn’t climb that morning. Somehow, despite climbing all week in moderation, I felt completely sated, if not a bit stuffed. As we packed up to leave, the apartment owners came by and offered us each a shot of homemade mirto, a traditional Sardinian digestivo made from blueberry-like berries soaked in vodka and honey for 40 days. They spoke no English, and none of us spoke much Italian, but the meaning of their toast was crystal-clear: buon viaggio—and come back soon.

Getting Seconds

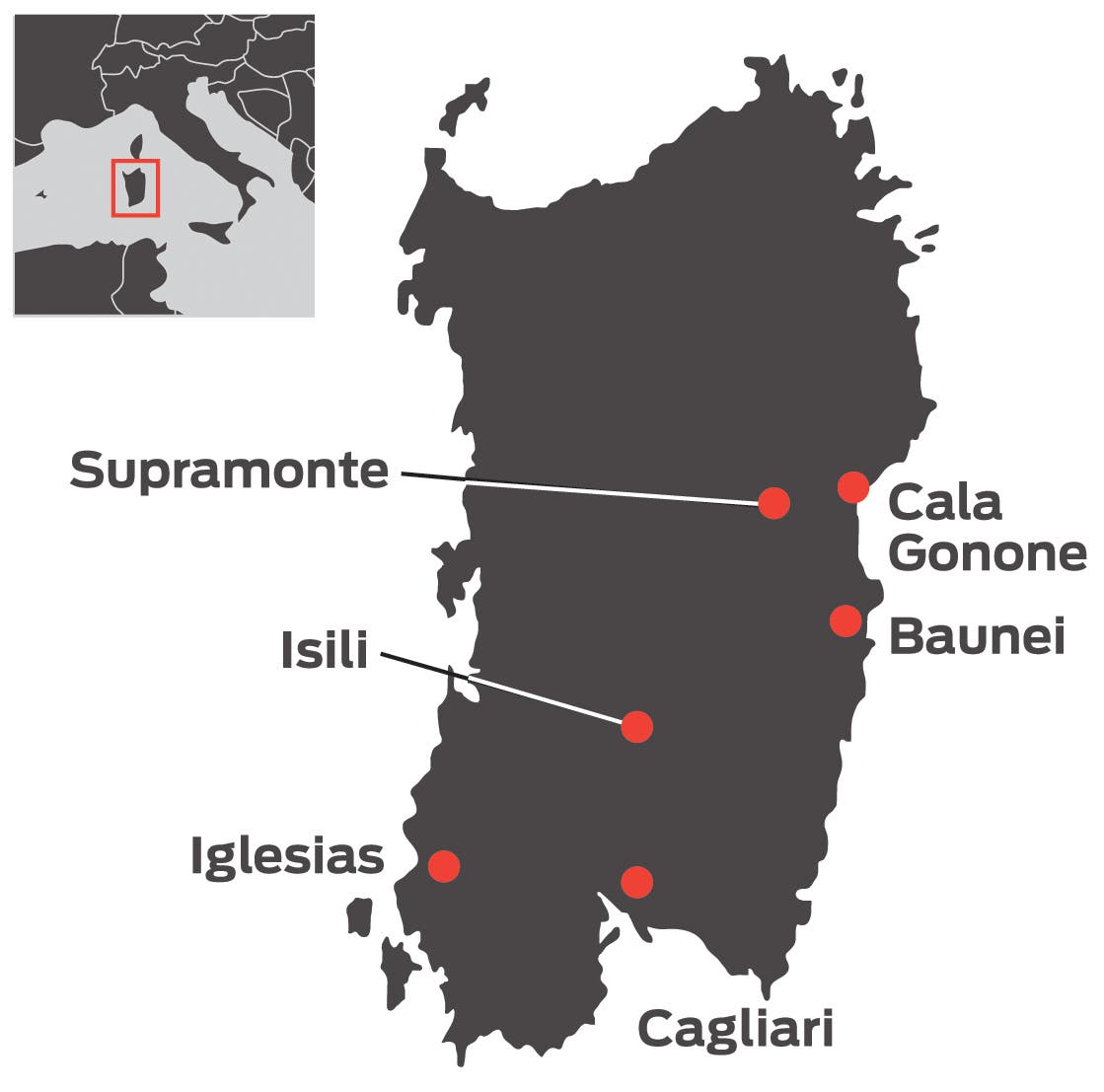

Got more than a week to climb in Sardinia? Lucky you. below are some of sardinia’s other popular areas. none is more than about three hours’ drive from cala ganone.

Supramonte: The mountains west and south of Cala Gonone are home to cliffs up to 1,000 feet high, including Monte Oddeu, Súrtana, and Gola di Gorrupu, and new routes are established every year. Depending on the route, a trad rack may be useful or essential.

Baunei/Ogliastra: South of Cala Gonone, accessed by a winding mountain road or a roundabout trip on the highway. In addition to offering hiking access to the Goloritzè spire, this area holds the wild seaside mini-wall of Punta Giradili (routes up to 12 pitches). Nearby Villagio Gallico is an excellent crag within day-trip distance from Cala Gonone. The main cragging area, Jerzu, is high in the mountains—a good destination in warmer months. The Lemon House in Lotzorai is a good central basecamp; the British expat owners, Peter and Anne Herold, have a wealth of information on local climbing and mountain biking (peteranne.it).

Isili: One of the big centers of Sardinian sport climbing, these crags in south central Sardinia are famous for juggy, pocketed overhangs. Best for climbs 5.11 and up.

Iglesias: Closest major climbing center to Cagliari in the south of the island. The main area, Domusnovas, has more than 500 bolted routes at all angles.

Sardinia Beta

Season

Summer is hot and crowded. Winter can be rainy. Spring and fall are perfetto.

Getting there

Fly direct from various European countries and rent a car or take a car ferry to Olbia in the north or Cagliari in the south. Olbia is closer to Cala Gonone; Cagliari has more flights and sits closer to the island’s other climbing spots.

Lodging

Cala Gonone has many hotels, but try an apartment finder like airbnb.com to find a place where you can cook at home instead of eating out (save money and exploit markets). There is also pleasant free camping in the woods along the road to Buchi Arta.

Food

Find several supermarkets in the town center; beware the midday closure, usually 1 to 3 p.m. A small deli on Via della Pineta has delicious pre-cooked dishes and is open during lunch.

Guidebooks

Maurizio Oviglia’s fifth edition of Pietra di Luna (€50, 2011, English edition) is the comprehensive guidebook for Sardinia, by its most prolific new-router. If you’re only climbing around Cala Gonone, Arrampicare a Cala Gonone (€20, 2013, with English beta) is cheaper and slightly more up-to-date, but it lacks the helpful star ratings of the Oviglia guide. Find both at climb-europe.com.

Boats

Many outfits by the port rent boats (fit 5 to 6 adults). The author’s cost was €60 to €70 plus gas (about €30 for a full day). Boat shuttles to Cala Luna are about €25 per person, round-trip.