The Accursed Alps

"None"

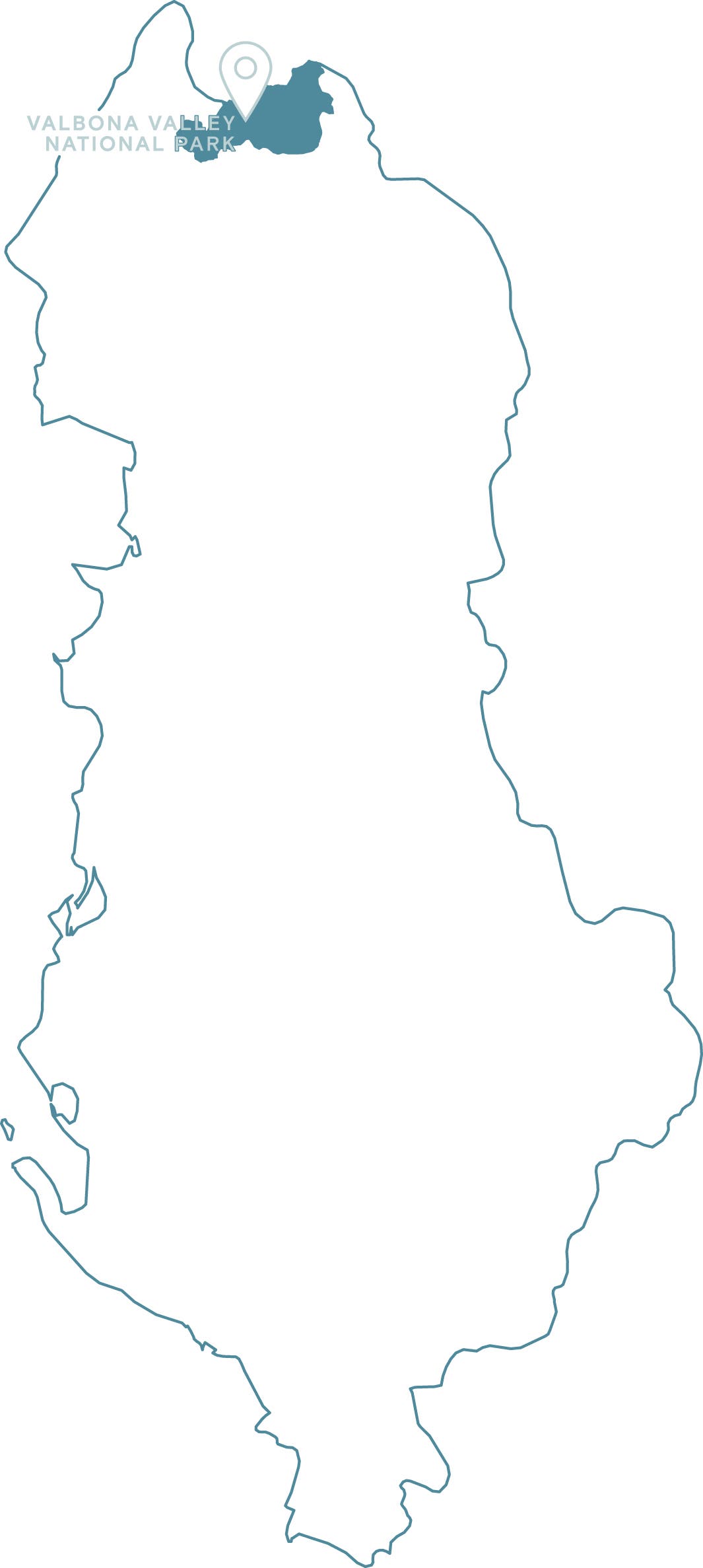

I was hardly surprised by my girlfriend, Rita’s, puzzlement when I tried to convince her we needed to visit Albania’s Accursed Alps, a wild mountain range along the country’s northern border. Most Americans are geographically challenged regarding this part of the world—though it borders Greece to the south and is just 80 miles across the Adriatic Sea from Italy. There are beach cliffs on Albania’s Mediterranean coast as well as crags inland near the capital city, Tirana. The short but aesthetic cliffs at Gjipea are a draw, plus a few emerging tufa hotspots near Tirana like Bovilla and Brar—the latter with rumored 5.15 Adam Ondra projects. But Valbona, in the far north—with its pristine alpine environment, soaring limestone massifs, and steep caves hundreds of meters high—is poised to be the Balkan Potrero Chico. In fact, it’s arguably the best limestone adventure climbing in Europe. And it remains mostly untapped.

As a wandering freelance photojournalist loosely based in California, I’d originally come to the Balkan Peninsula in 2017 on the hunt for stories that pertained to some 2,700 newly proposed—and some already active—hydropower projects that were compromising hundreds of pristine rivers and creeks in seven Balkan countries. Balkanrivers.net and its partners have worked tirelessly to document the biodiversity that could be lost were these waterways developed, having examined 21,747 river miles here and finding 30 percent pristine and 50 percent still in good shape. The region rests on crazy Karst topography, with limestone gorges everywhere—essentially the whole of the Dinaric Alps, 124,000 square miles that stretch from Slovenia south to Albania, with hundreds of climbing areas and Europe’s last truly wild rivers, holding populations of wolves, bears, lynx, and other species. But the limestone around these rivers kept sirening me in. This trip with Rita would include a short visit to Valbona for first ascents at a crag I’d discovered in 2017 with Wolfgang Schüssler, a German I’d met in the area.

Due to Albania’s unique history, climbing in the modern sense is scarcely two decades old. Rugged highlanders have lived at heights up to 4,000 feet and herded sheep since time out of mind, ranging up and over from the connecting Theth Valley to Valbona. They were rumored to solo low-grade couloirs and limestone passes with packs and guns on their backs, hunting wild goats for food—especially during the lean times of the Communist era. The country has a forgotten, old European, and arguably Turkish feel. Ottomans swept across the region many times, and today the country is 65 percent Muslim—though religious expression in Albania is very relaxed. The strong Albanian culture of besa (essentially, “hospitality,” as defined by a traditional set of Albanian laws, the Kanun, set down half a millennium ago) seems more pronounced—it’s a promise to take care of anyone who seeks protection, including the Jews who came during WWII, as well as Kosovars when Serbia invaded.

Secretly, I used Rita’s naiveté regarding the region to draw her in. I neglected to mention that my friend Catherine Bohne, who lives in Bajram Curri, a small city at the entrance of Valbona, and runs the nonprofit The Organization to Conserve the Albanian Alps (TOKA), had been swatted in the face and left for dead by a protective mother Carpathian brown bear on trails we would be using. Or that there were roaming wolves. Or that there were blood feuds so virulent unlucky family members have had to flee to other countries as refugees. And that behind the untold ongoing and proposed hydropower projects was a much-feared hydro-mafia—construction corporations/investors in cahoots with corrupt politicians to exploit the country’s waterways.

Specifically, we’d be landing in a hotbed of local activism, where a grassroots struggle to save Valbona Valley National Park and its pastoral and agricultural way of life was pitted against big money and construction. All too often in climbing, an area gets developed and then trouble hits from development or closures. But here, climbers and other activists are stepping in beforehand. It’s a good model: Get to know the issues and be a part of a positive, sustainable solution up front rather than diving in, drills awhirring, then getting a “wake-up” slap later.

Valbona Valley National Park, comprising 20,000 acres and the nearly 20-mile-long Valbona River Valley, has an illegal, ongoing hydropower project that launched in January 2016—and that the locals have been actively protesting since its inception. (It started with the forging of signatures at a public consultation prior to building, to win approval.) Falling rock from blasting threatened houses in the tiny enclave of Dragobia in the park, which inspired the locals to stage a one-day roadblock to make their voices heard. Clean drinking water had been compromised due to the diversion of water, not to mention its impact on the local irrigation systems. And endemic species seen nowhere else in Europe stood to be extremely challenged. Sustainable activities that could support the region like fishing, kayaking, climbing, hiking, and homestays with local shepherds were being lost to short-term profit.

Neither did I mention to Rita that Albania still had half a million crumbling bunkers, built for each family to hide in at the behest of the paranoid dictator, Enver Hoxha, who’d believed he could be attacked at any time—and who, guided by extreme socialistic principles, has been given the dubious credit for the deaths of 100,000 of his own people courtesy of starvation, forced labor camps, and a secret police that disappeared dissenters during his 40-year reign. And that only in the last few years had the Accursed Alps even gotten a map because Hoxha rightfully feared that the inhabitants would walk over the range into freedom in Montenegro.

I love falling off the map, and in Albania you still can.

* * *

In 2017, I’d bounced around the Balkans, a frenetic pinball of energy connecting dots of local grassroots activism protesting hydropower—and hitting up a few climbing venues. For some 20 years, I had worked at the fringes of activism, starting with the Access Fund in the early 2000s in Humboldt County, bringing together climbers, local land managers, and Native American tribes. In fact, the bulk of my photos, writing, and work as a climbing and backpacking guide has been aimed at promoting conscious environmental and wilderness engagement.

In the Accursed Alps that October, I met the wayward Wolfgang Schüssler, who’d also been captivated by the region. He was typically German—with his thick accent, deep voice, and direct way of speaking, he could have been the lead singer of Rammstein. In Valbona, he offered a sampling of the limestone: riverside boulders with short sport routes and highballs positioned next to swirling rapids—just a handful of miles upriver from where the new hydropower plant had started sucking the river dry and less than half a mile above a smaller, pending power station.

We also climbed at a sport crag Wolfgang had developed, “the Cave.” As the sun sank, we climbed a 100-foot bolted line along a cliff band a thousand feet up the slopes of Maja Kollata, one of the region’s tallest peaks at 8,358 feet. The positioning afforded views deep into the ring of mountains that guarded Theth, the huge valley to the east. Wolfgang warned that the limestone walls on the higher peaks, though enticing, were akin to making first ascents on the moon—serious endeavors due to a lack of pro, patches of dubious rock and running water, and painfully long, steep approaches. We thus decided to explore more localized roadside cliffs, and on one of my last days in Valbona struck it rich.

Just five minutes from the car above Bajram Curri, just before the entrance to the park, Wolfgang and I crossed a slope to access an untouched half-mile band of limestone. Painfully visible from the village, it still got lost in the vast sea of nearby cliffs. As we approached, we didn’t seem to get much closer to the base, yet the rock kept growing over and behind our heads. We’d conservatively estimated the overall height at 400 feet, but as we got closer we realized that the wall also overhung 100 feet. “Holy Jesus—quite a bit steeper than expected!” exclaimed Wolfgang.

This was the game-changer we’d been hoping for—the mother lode of limestone bonanzas. The cave—named Vrajaqa, on land owned by the Mucaj family—had soaring, sculpted tufas on solid orange- and blue-striped stone. It was futuristic, with room for multi-pitch 5.13s on up.

At the base of the left side, on a panel that looked like the most accessible option, we moved vegetation to find a foothold and sent an eight-inch, black- and red-striped fire salamander scurrying. Wolfgang led, trad gear racked on his harness, plowing upward on virgin limestone, linking dihedrals to mantels to delicate rockovers. The solid 5.10+ climbing ended at 200 feet in some trees. This wall alone could house a dozen quality lines up to two pitches.

That first day we climbed two other FAs, both in the central cave and both of which brought us 80 feet up to the overhanging portion of stone. Dust, Mud, and Turtle Blood was an exciting 5.9 R, so named because the whole route felt like climbing on dust and ancient muds—and because at the belay we found a turtle shell stuffed into the crack, no doubt by some large raptor. Immediately left of DMTB, Wolfgang added another spicy 5.10 connecting a thin seam and runout face. Atop the pillar, we lingered to gawk at the potential above. Looking out the giant maw, I felt like a speck of krill about to be swallowed by a whale. We made plans to return the following year with the bolt gun. It felt almost criminal to leave all this stellar rock unexplored.

* * *

Eight months later, Rita and I found our way from neighboring Kosovo after 42 hours of flying to the edge of the Accursed Alps, named by would-be invaders who gave up trying to cross the forbidding mountains into Albania. We arrived just as golden late-afternoon light bathed the peaks in a Maxfield Parrish afterglow. It was nearly July, but stubborn spring snows clung to the hundreds of jagged, toothy limestone crags that ring the ridges and summits of dozens of the 8,000-plus-foot peaks on both sides of the Valbona Valley. We stayed at the Arben Selimaj guesthouse inside the park, which is home to some 400 people and was recently listed in a National Geographic article as one of the best places to visit in Europe. We were only minutes from the boulders and Wolfgang’s nascent Cave crag.

The following day, Rita and I shouldered our packs and hiked the half-mile upriver to one of Wolfgang’s other crags. He has not-so-secret plans to get the locals fired up to climb so he might have partners—and so the locals, in turn, might put up routes and become guides, drawing traveling climbers to the valley and creating a more sustainable income stream than hydropower jobs. There was ongoing construction on the smaller power plant just downstream, and we could hear power tools during the day. Gener 2 was the main company bringing in jobs, and the work carrot they’d dangled had split families apart—one brother had taken work with the company while another was traveling five hours to the Tirana courts to protest it. That day, Gaz, the Selimaj’s teenage son, joined in, putting us to shame by barefoot-climbing the short, scenic sport routes up to 5.10 that we did in rock shoes—on his first day out. Gaz studies tourism in Tirana and seems poised to take over running the family guesthouse one day.

The Selimajs are just one of many families that run guesthouses and guiding services for hikers and organized transport for visitors to this region. These include stay options with the local shepherd families, who still tend huge flocks of sheep with the help of the intimidating Šarplaninac shepherd dogs. (These massive canines can weigh up to 100 pounds—if you come across one while hiking, just pray the shepherd is within earshot to whistle the growling dog down.) Up in the Accursed alpine, you can do a home stay with a local family and dine on sheep’s-milk yogurt and fresh cheese, Kolça beer, and the deadly raki, a 50-proof liquor made of grapes or plums that everyone in the Balkans seems to have a secret stash of and will imbibe at any and sometimes all hours of the day. Just ask Rita: Her raki hangover from my birthday bash at Alfred Selimaj’s, a cousin of Arben’s with a larger guesthouse across the road, left her hammock-bound for 15 hours.

Rita and I spent our first full day in the shadow of Maja Kollata. The first route on the 40-foot block just above the river would be my lead, a splitter crack that’s an anomaly in the sea of sport lines in Albania. Jet lag be dammed, I was psyched. Wolfgang handed me his rack—a bunch of fucking knotted cords and nuts that were way too small. Germans … Below, the picturesque turquoise pools along the Valbona River mixed with raging fourth-class whitewater, the river still at full flow above its imminent diversion.

On our third day, we decided to tackle the Vrajaqa cave. En route, we stopped at the street bazaar in Bajram Curry where we picked up a watermelon, Italian wine, and some swirly purple-and-white knockoff Crocs for about 80 cents US. We toasted the frightening-looking, neon-green-striped black spider on the belay rock, and I held the rope for Wolfgang as he launched up an innocuous-looking 5.8ish dihedral with the drill. His goal was to place anchors atop the “Yoni Cave,” a much smaller but very steep and solid subcave within the larger Vrajaqa cave. From here, you could link into the dripping tufa lines above.

I did a more dynamic belay than I ever have, dancing out of the firing line of launched blocks—the edges of the cave, it would turn out, were chossier than the middle. Nonetheless, Wolfgang’s efforts would lead, in the end, to seven total routes from 5.8 to 5.11 on the Yoni feature. Rita, who had never seen someone put up an FA, was surprised by the rivers of cascading rock.

Wolfgang, psyched with our progress, left ahead of us that afternoon, and we got separated. Rita and I found a less steep way to descend. We passed a few cows and then a hugely smiling man and woman, the cattle’s owners. We would learn about besa that day—the Albanian way of greeting outsiders with incredible warmth. Syrian refugees have been thrilled to serendipitously wander through this country. Rita and I knew about two words of Albanian, and they about the same in English. But the smiles and insistence that we follow them ended with us visiting their two-story home, with its incredible view of the days’ climbing and surrounding peaks. As we shared glasses of fresh milk on their patio, we did our best to communicate. When we didn’t understand their emphatic efforts to communicate with us in Albanian, the man would simply raise his voice. Rita and I just smiled and nodded. Soon we were all smiling, enjoying the view. That Maxfield Parrish light on the soaring peaks, and the dream of falling off the map having come true.

On our final day in Valbona, things turned an unexpected corner. Wolfgang mentioned a banner—in fact, a 20-by-40-foot banner weighing 60 pounds—that he needed help hanging. Reading Po Flet Valbona (“Let Valbona [the residents] speak up and be heard”), the banner protested the hydro projects in the valley. Catherine Bohne of TOKA, with whom Wolfgang is a good friend and whom he supports with his climbing/ropework expertise for activism work, had tasked Wolfgang with hanging it from a cliff in full view of the park highway.

To get into position to hang this vinyl behemoth required fording a third-class section of the Valbona River with the banner plus our gear-laden packs, sending a first ascent on a virgin cliff, and then getting back across the river safely. All without raising the ire of the hydro-mafia that would surely be driving by midday. Thankfully, the vipers left us alone, the razor-sharp death blocks stayed put, and the 5.10 splitter I led was on par with any Yosemite classic. And when the head of security for the hydropower saw what we were doing, he was kind enough to only scream at us across the river—we were easy targets on the wall should he have cared to up the ante. Two subsequent near-drownings on the return made it all the more memorable. Another stellar day in the Accursed Alps …

The Activists

Uta Ibrahimi

Years Climbing: 5

Home: Pristina, Kosovo

Job: Owner, Butterfly Outdoor Adventure guide company in Kosovo

Conservation Goals: As a champion for the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, Uta focuses on environment and gender equality in the Balkans.

Through my climbing in the Himalayas [Ibrahimi has climbed five 8,000-meter peaks] and elsewhere, my idea is also to promote the Balkans—my home and my passion. Many people have almost no information about this region even though we are in Europe and have some of the best hiking, climbing, kayaking, and cycling. Some people don’t even know where we are on the map. Some others think there is still a war in the Balkans, even though this is one of the safest places in the world. My goal is to help change these unfortunate misconceptions.

I do a lot of hiking, climbing, bouldering, and trail running in Valbona. I train through the valleys and mountaintops that connect Valbona and Theth national parks. The northern part of Albania is paradise for anyone who loves the outdoors. It has all that I need to prepare for expeditions to the Himalayas.

My passion comes from growing up in the mountains and spending time in the place—the outdoors—that brings me peace. That peace and the desire to explore new and familiar places keep me going. They sustain my passion. People who love the mountains and the beautiful people who inhabit them know this without having to make sense of it. It is the same as breathing.

The Balkans are still wild, and visitors—and locals—feel that immediately. This is what keeps people coming here and makes them fall in love with the region. This wildness is what makes it precious, but also what makes it so vulnerable.

Wolfgang Schüssler

Years Climbing: 15

Home: Frankenjura, Germany

Job: Social worker, CEO of Lobo Ventura guide company

Conservation Goals: Open new climbing areas in Tropoja/Valbona—the larger region that houses Valbona—together with locals in order to create sustainable tourism.

The Valbona region has been isolated for a long time. When I first came here in 2016, I was amazed to see that such a wild and unspoiled place still existed in Europe. The valley has been, due to its hidden position, a reserve for all kinds of flora and fauna, with an incredibly diverse ecosystem. One night while camping, I heard a wolf pack communicating around the river. It must have been five or six wolves—I will never forget the soundscape of these wild animals.

I met amazing people in Valbona, and decided to support them by teaching them the climbing skills to help create a mountain-rescue team. My then girlfriend and I managed to get some used climbing gear and a mountain stretcher from the Mountain Rescue Team in Berchtesgaden, so that rescues on difficult terrain would be possible in Valbona.

But soon after I arrived, construction started for hydropower. I believe there are better ways to generate green energy—and the destruction of a diversity hotspot like Valbona does not make any sense. There is no second Valbona, and the international community should be pushing those in charge of the development toward a better solution.

I have realized, too, how hard it must be in Albania to challenge big corporations, as people are scared to speak up because they might get into trouble or have to speak against their own family members, who might benefit from employment by the construction companies. I hope that by developing the climbing potential, there will be a slow increase in tourism that will create sustainable work opportunities for the locals.

Rok Rozman

Years Climbing: 0 (professional kayaker, paraglider)

Home: Radovljica, Slovenia

Job: Activist and lead at the nonprofit Balkan River Defence

Conservation Goals: Giving a voice to locals in Valbona and bringing international attention in order to apply pressure on the Albanian government and their shady business around hydro development.

You don’t develop passion by reading books or watching documentaries. You must visit these places, smell them, sense them, laugh, shiver, and feel lost and scared. I love nature and good people. Both are endangered in places that I call home. I wouldn’t defend these rivers if I didn’t know them, and this is why we are taking people on and to the river. To bring global awareness to this case, our caravan—kayakers, hikers, and climbers from all around the world—will lead the charge and risk getting arrested.

This blockade was one of the best things we’ve done as part of the Balkan River Defence (balkanriverdefence.org). Things happened spontaneously; we rolled into this magical valley and saw the dam construction—this absurd, unnecessary destruction driven by greed. Despite all the passionate work by the local NGO TOKA, with support from numerous international organizations and individuals, these guys were bulldozing the riverbank even though they had no construction permit. So we invited leaders from villages in Valbona Valley to discuss how we can help them. Voicing anger, sadness, worry, and unconditional love for the river, the locals said they were almost out of energy to resist. But we stuck our heads and hearts together, and came up with a solid plan.

These are the last wild rivers in Europe. They now serve as biodiversity laboratories where scientists working in river restoration study how rivers in Europe should look. While the United States is investing in dam removal and Central Europe is doing the same with restoration projects, here we face the absurdity of the destruction of the last self-sufficient European river ecosystems. These rivers are a connection to tradition, a sustainable way of living, and sanity. Yet they are vulnerable because they stand in the way of aggressive capitalism.

That day during our protest (8 of our 20 protesters were climbers), nobody was arrested since the police knew they had no legal right to do so. Meanwhile, our protest made the Albanian and international media, and spurred the regional judge to file a lawsuit against the dam-construction company, the outcome of which we’re all awaiting. This protest was proof that we can take efficient and peaceful action to save these rivers that are so important to the local citizens and the health of our planet.

Valbona / Accursed Alps Logistics

Where to stay

Valbona has numerous guesthouses, as well as upscale hotels. $10–20 gets you a good dinner and breakfast plus a tent site or a nice shared room; closer to $40 will get you a sweet luxury hotel room and usually breakfast. I recommend staying with the Selimaj family: journeytovalbona.com/hotel/arben-selimaj-guesthouse/

Eats

Valbona offers amazing cuisine as well as raki. But beware the raki! This heavy liquor offers easily coerced and massive hangover potential—the locals often make it themselves and will set you up with a friendly shot or two at any given hour. Goat, sheep, and things made from milk are fresh and abundant. In the towns and cities, you’ll find cafés with good coffee and baked or fried burek, a savory pastry.

getting around: Fly into Tirana. If you rent a car in Albania and stay there you will save serious coin, as border crossings require special (read: $$$) insurance/EU license plates. Whilst driving, watch out for suicidal cows lounging on blind hairpins, packs of horned goats, lanes obscured by fallen rock, potholes, locals wandering all over the roadways at any hour, and very few streetlights. Toka-albania.org has lots of great info on the Albanian Alps and the ongoing struggle against hydropower threats.

When

Late spring, summer (find shade!), and fall—unless you are keen to winter climb, with oodles of rad FAs to be had on the surrounding peaks and couloirs.

Guidebook and local ethics

There is no guidebook as of yet, but you can visit climbingalbania.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Valbona-Topos.pdf. Valbona offers true adventure climbing and a plethora of FA options—be your own guide. The Vrajaqa cave, with only a dozen routes so far, has futuristic potential for perhaps 50–60 lines, some three or four pitches and up to 5.15. As per usual before bolting, get permission and work with the locals. If it takes gear, place it. You can contact Wolfgang Schüssler (wutschgo@hotmail.com), who works closely with the locals to keep bolt ladders from dominating.

Key Albanian phrases

- Gezuar! = Cheers!

- Mira pof shim = Goodbye

- Faleminerit = Thank you

- Mirdita = Good afternoon

Bennett Barthelemy calls California home, but the warmth of the Balkan people and the mythical limestone throughout the region keep him coming back.