The History of Hard Sport Climbing in Boulder's Flatirons

"Rob Kepley" (Photo: Rob Kepley)

This story is a supplement to the feature Frozen in Time: A look at the new-school sport climbs of the Flatirons, Colorado on newsstands now in the July 2018 issue of Climbing Magazine. Subscribe here: print, digital.

Four names you’ll find often in the Flatirons guidebook are Colin Lantz, Bob Horan, Dan Michael, and Paul Glover, who among the many Boulder climbers in on the Flatirons sport-climbing gold rush, had a consistent and prolific presence in the 1980s as well as put up some genre-defining sport routes that retain an aura to this day. Lantz has mostly moved on to mountain biking, but Michael and Glover and Horan still climb often—and often in the Flatirons. They are longtime Boulder, Colorado, fixtures and have been at it for decades.

Here, we’ve compiled Q&As and/or personal essays about that magical period in the Flatirons from each climber, to capture the feel of the era. It was a formative time in American climbing, when sport climbing was only a few years old, still not widely accepted, and often baffling to land managers, who were now seeing climbers up on the rock with loud rotary hammer drills when in the past climbing had been a quiet, obscure, near-invisible activity.

Sport climbing took root in North America in 1983 in Smith Rock, where Alan Watts rappel-bolted the 5.12b pocket climb Watt’s Tots. With the blank, clean faces of Smith as a template, climbers began to look for similar features in their local areas. They also took trips to Europe, the crucible of sport climbing, where the clean, sweeping, vertical limestone of the Verdon and smooth, pocketed swells of Buoux were the gold standard. As a result, many of the earliest sport climbs in the Flatirons (and in nearby Eldo) stuck to the script, climbing blank, slabby faces and arêtes. Soon, however, with the rise of radically overhanging areas like Hueco Tanks, the Enchanted Tower, and American Fork, first ascentionists began looking for steeper rock in their own backyards, the Flatirons included. While the east faces visible from town are all slabby and moderate, the north, south, and especially western aspects of the Flatirons often overhang—the trick is finding the good, featured rock with either varnish or water hardening.

The first overhanging Flatirons sport routes began to appear around 1987, and as local climbers developed an eye for this new terrain, more and more climbs in this genre appeared. Groundbreaking routes include Lantz’s massive hanging roof Chains of Love (5.12b/c; 1989; the only rock climb ever featured on the cover of TIME Magazine) in Fern Canyon; Michael’s thin, gently overhanging Slave to the Rhythm (5.13b; 1987) on the East Ironing Board; Horan’s sickly steep hueco-haul The Guardian (5.12d; 1987) in Skunk Canyon; and Glover’s bulging, pocketed Touch Monkey (5.11b; 1987) on Der Zerkle on Dinosaur Mountain. All radically steep, with big pockets, huecos, and long, powerful reaches, these and other routes showed what was possible and just how much potential was left. When the ban hit in 1989, Boulder locals were just getting started. Despite this setback, climbers carried on, and steep, new climbs began to appear in nearby unregulated areas like Clear Creek Canyon and Mickey Mouse Wall, and then eventually spread to Rifle, where activity began in earnest in 1991.

In other words, the Flatirons helped pave the way for Rifle. Chew on that the next time you’re gasping in the upside-down double-kneebar rest on Super-Jumbo Pump-a-Rama-Thon, wondering just how it is we got here.

Here are four interviews and essays from the climbers behind the Flatirons’ hard sport climbing revolution:

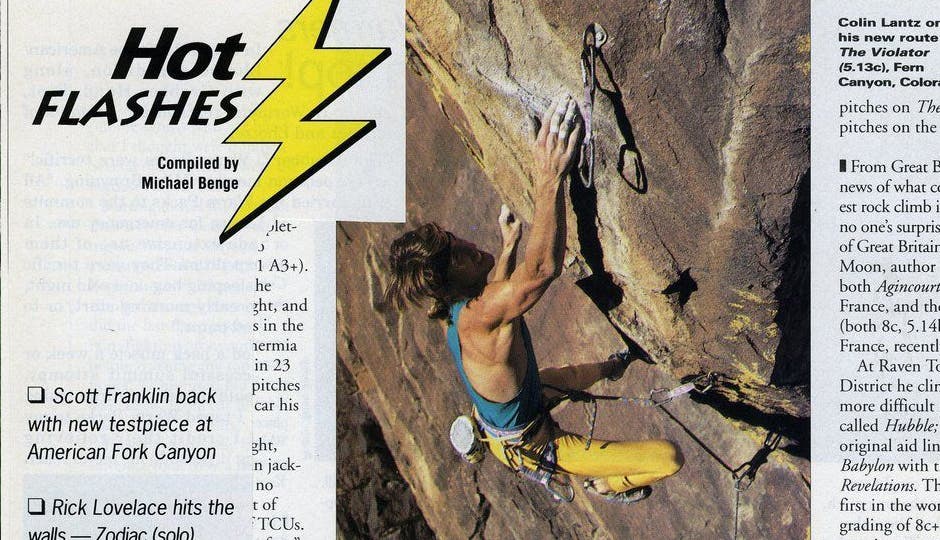

Interview: Colin Lantz

Colin Lantz, was in the 1980s and 1990s a driving force with hard first ascents in Colorado, from the Flatirons to Eldorado to Rifle and may, in fact, have Colorado’s first 5.14. Read the interview.

Personal Essay: Bob Horan

Bob Horan is one of Boulder’s most prolific first ascentionists, going all the way back to the 1980s, and he continues to ferret out new gems to this day. Read the full story.

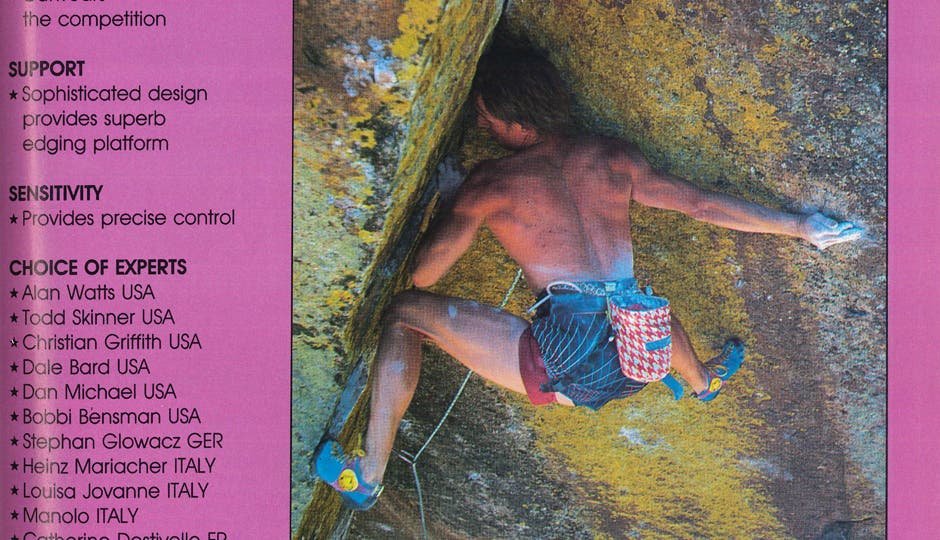

Interview: Dan Michael

Wiry, limber, and with fingers of steel, Dan Michael put up lasting Flatirons testpieces like Slave to the Rhythm (5.13b) and The Fiend (sandbag 5.13c). Read the interview.

Personal Essay: Paul Glover

Paul Glover has also been a driving force behind Flatirons bouldering, ticks hard shoeless roped ascents, and began developing sport routes while still a high schooler. Read the full story.