The Samburu Climbers of Kenya Find a New Way of Life On the Stone

"None"

Just watch out for elephants,” was the only beta we had for the approach, from a friend in Nairobi. As dawn painted the arid brushland of northern Kenya a soft gold, the sun crept up the amber face in front of us: Mount Ololokwe (6,480 feet), a mile-plus-long big wall exploding out of the savanna. Hacking through the thick bushes ahead was our guide, Peter Lemaiyan, the threads of his bright red shuka (the traditional garb of his Samburu tribe) catching on acacia thorns.

Another of Lemaiyan’s friends was to meet my partner and me on top of the massif to guide us back down through its dense leleshwa forests, which shelter cape buffalo, baboons, and, according to Lemaiyan, a solitary leopard. It hides in the brush and hunts by night: “Lakini unaweza kuona macho (But you can see the eyes),” he told us in Swahili. Lemaiyan would meanwhile return to watch our Land Cruiser, tucked away in the trees below, making sure no goatherds would be tempted to explore its contents. In Kenya, pulling off a climb can take a village.

Four hours later we were bleeding, drenched in sweat, and proud of ourselves—just for reaching our route (The Schnoz, 5.9 R). It had been a fight, battling through spiky aloes, hanging on vines, and sliding between enormous hidden boulders. At the wall, I was startled by a low growl in the distance. Lemaiyan laughed. “Bodaboda tu (Only a motorcycle)”—one that was echoing from the highway along the horizon. The climb itself offered excellent movement up solid slabs featured with crystals and elaborate dimples—but, as is common on Ololokwe, little protection.

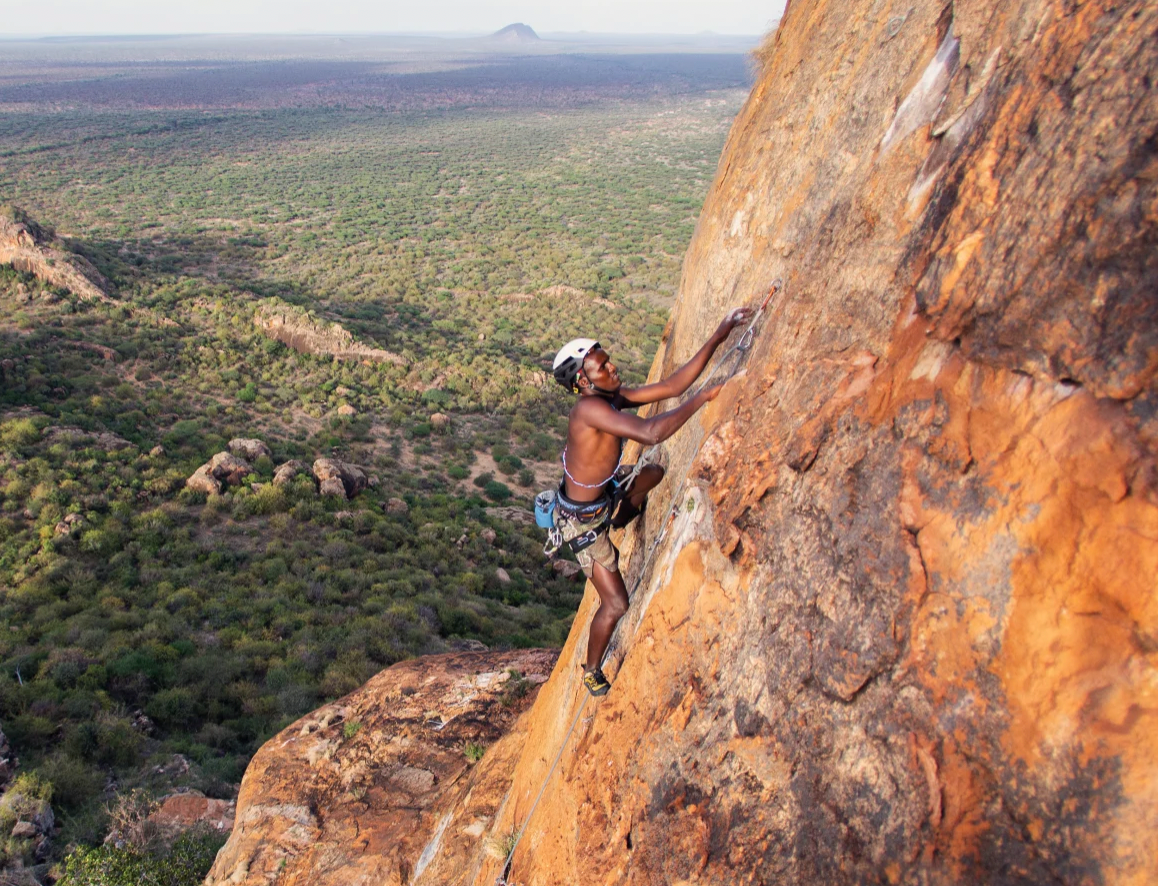

Here, far north of the game reserves and safaris that have made Kenya a tourist destination, lie rugged ranges home to few but nomads, wildlife, and occasionally rock climbers. Wild monoliths like Ololokwe loom over Samburuland, the ancestral home of the pastoralist Samburu. The region’s immense gneiss faces see few ascents save by members of the unorthodox local climbing community and the occasional visiting international team. The potential for new, daring climbs feels endless.

As development has slowly expanded, particularly in the last decade, the area has become a confluence of cultures: ranging from the eclectic climbers of Nairobi, seven hours distant; the surrounding tribespeople, who live in a rapidly changing world; and, sometimes, climbers from the global north. Few places provide the opportunity for such raw adventure and sustainable, symbiotic development.

Below the route, Lemaiyan watched me rack up and mount the initial gneiss slab by clambering 25 feet up a thicket of vines. As I fiddled in my first cam, his eyes narrowed in concentration, studying: Lemaiyan wasn’t just our guide for the approach. He’s a climber, too.

“Few of them come back”

Although climbing on Mount Ololokwe began about six decades ago, it’s recently taken off with new fervor. In 2013, when the Kenyan climber Parag “Fish” Shah of Nairobi first arrived under the intimidating 1,400-foot southern face, he knew of only three routes up its blank slabs and steep jungle gulleys. Since it was first breached in 1965 by Robert Chambers, an expatriate British scholar who taught in Nairobi, and Henry Mwongela, a young Kenyan climber, the massive wall had warded off most attempts: All Shah had to go on were old trip reports that retold of encounters with grumpy rhinos and of epic, moonlit descents accompanied by the cackling of hyenas. Elephant skulls had even been found on ledges halfway up the wall.

“Maybe it got washed down by the rains, but maybe an elephant fell and died in that spot,” Shah told me.

Shah, who got the nickname “Fish” for the spectacles he wore as a kid, has dozens of first ascents across the country, many on these remote desert peaks. As chairman of the Mountain Club of Kenya (MCK), he’s partnered with the many roaming expatriates who pass through Nairobi as well as helped his countrymen develop into strong, competent climbers. I first met him as an American high-schooler in Nairobi, where my family had been based since 2004 and where I learned to climb.

On that exploratory mission eight years ago, Shah had traveled north with his partners Alex Fiksman, a Kenyan citizen, and Tom Gilbreath, an American. The trio hoped to finish a line begun in 1971 by Ian Howell and Iain Allen—the energetic British expats who put Kenyan climbing on the map in the 1960s through the early 2000s—up a severe section of Ololokwe’s southeastern face known as the Oasis Wall.

Howell and Allen themselves first failed even to reach the wall, turning around in the steep jungle: “The huge grey head of a black rhino emerged from the vegetation about 80 feet above and [it] began thundering down toward me,” Allen recounted in an email. “We leaped at the same time behind [a] boulder. To our right, no more than six feet away, the rhino charged past … its massive body crashing through the thick brush.”

Their next attempt took them little further: Joined by an American climber, Phil Snyder, the two managed four pitches up the lower slabs in the grueling heat until the wall steepened and protectable features vanished. The rest is lore: As Shah recounts, they “hammered a wooden wedge into the rock” to abseil off.

Shah, Gilbreath, and Fiksman followed the original line for two and a half pitches. But when Fiksman found himself runout 35 feet horizontally from his only piece, they backed off—after spending a lonely night on a ledge buffeted by the cold midnight wind.

Shah says the attempt put the gravity of the wall, and the achievements of “the Ians,” as they’re widely known to Nairobi climbers, in perspective: “We modern climbers with modern gear didn’t get up to that high point that these wazee [elders] got to.”

For their party, as for others, the route was but one concern. The local Samburu community had traditionally been wary of the occasional climbers who’d skirt their villages to access the rock. Ololokwe is considered sacred by many Samburu—and you understand why as you watch the massif collect the morning clouds that rise off the savanna, unveiling an almost prehistoric landscape where wandering elephants kick up distant swirls of dust.

Climbers the world over are drawn to powerful walls, usually with a shared reverence. Yet in Kenya, which was under British rule from 1895 to 1963, the specter of neocolonialism complicates climbing access. Historically, the MCK advised climbers to avoid paying local communities for land use, lest it create unhealthy dependencies. However, most of the country’s established crags rely on relationships, painstakingly built over years, between climbers—Kenyans and those from afar—and the rural communities.

Such a rapport began in Ololokwe after Shah and company, initially rebuffed by community game rangers, were retreating from their first Oasis Wall reconnaissance. As they reached the dusty highway, a Samburu elder named D’pa driving an ancient, rattling Land Rover flagged them down.

“You know how it works in the bush,” Shah says. “Word had already spread around: These wazungu”—the catchall term for foreigners, white people, or just Nairobi city slickers—“want to climb.”

The climbers sat down with the enterprising D’pa in, Shah recalls, “some shady nyama choma joint”—one of the many roast-meat vendors that broker such arrangements in Kenya. “By then they were getting familiar with how climbers operate, what we were trying to do on the face,” says Shah, and D’pa offered to hire out some donkeys to help carry gear.

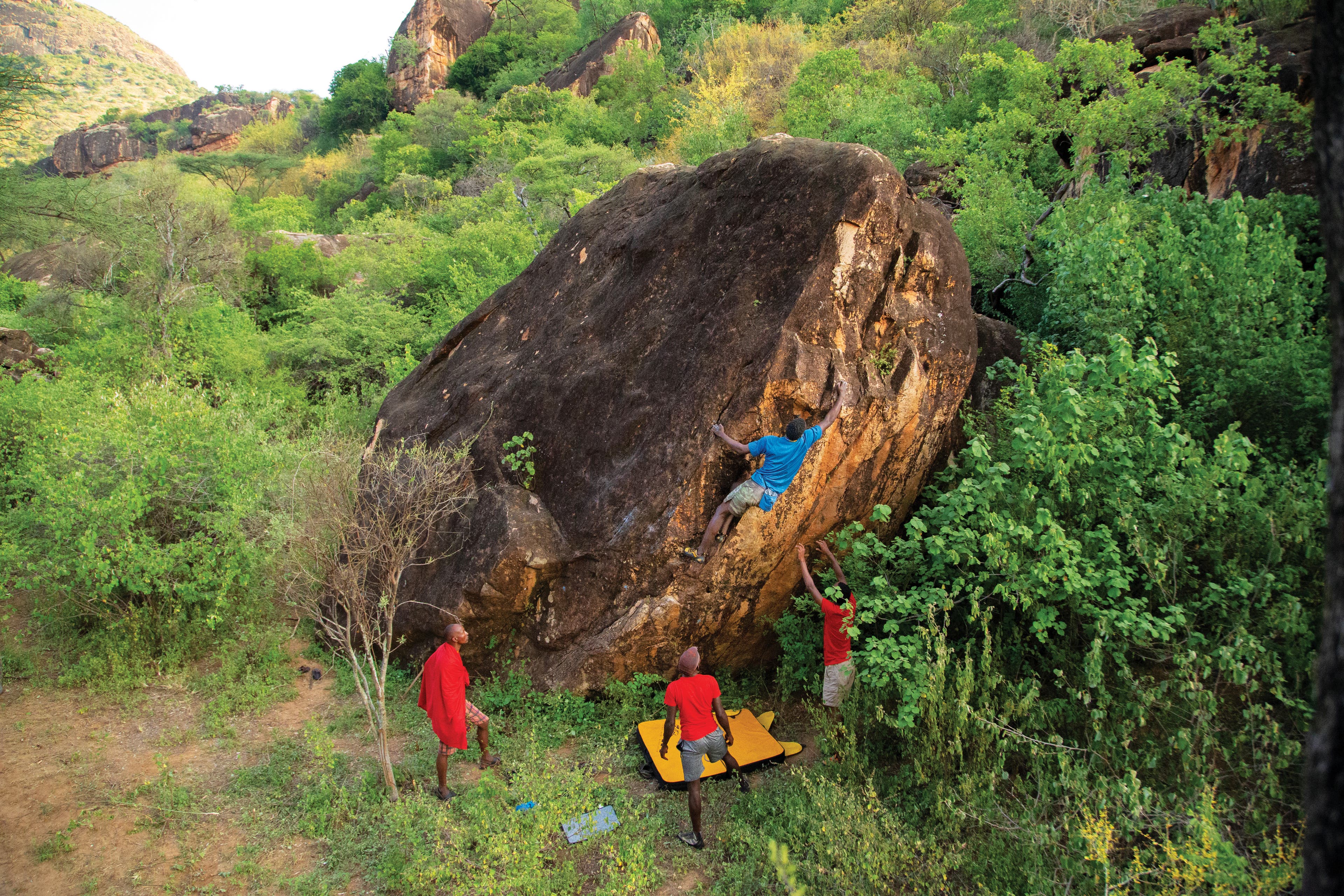

It turned out that D’pa managed a community ecolodge called Sabache nestled behind Mount Ololokwe, offering campsites and amenities; in the visiting climbers, he saw an opportunity for tourism dollars. Soon D’pa began sending several Samburu moran—the young men of warrior age (13 to 30)—as guides, helping climbers weave through the thorny forests to the gneissic formations, following game trails the moran had known their whole lives. At first the moran guided only a few parties a year, but the numbers increased as word spread. After several years, the young men were keen to try the sport themselves.

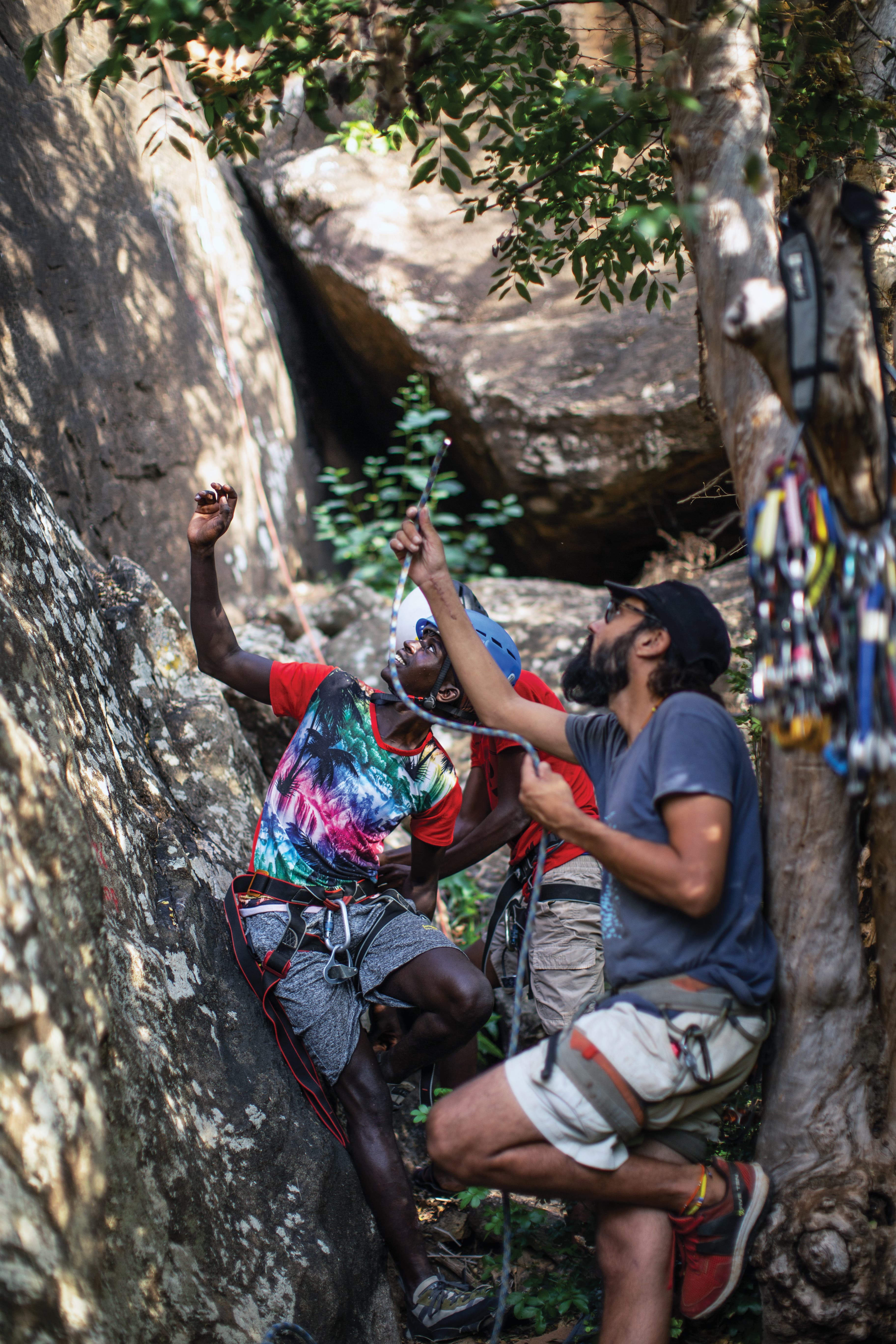

“The idea was for [the moran eventually to be able] to take guests climbing,” says Shah. With another veteran of Kenyan bush climbing, Andrew Wielochowski of the UK, Shah began visiting Ololokwe with gear donated from the UK and teaching the moran traditional gear placement, aid climbing, and, after a visiting German duo established a sport crag near the Ololokwe basecamp, how to clip bolts.

Wielochowski is a onetime Outward Bound instructor who lived in Kenya from 1978 to 1986 and has returned annually ever since, his name speckled across the old guidebooks tucked away in the MCK clubhouse. He had observed a natural familiarity in the trail guides: “These guys were so at one with the local area, so at one with nature there; they just romped around on easy cliffs. Sometimes they’d stand and watch [climbers], and I thought, ‘They obviously would love to be there, would love to have a go at it.’”

Shah says, “[The moran are] really strong, but they don’t have many people to climb with and are not getting exposed to any other climbs.”

To date, no Samburu have attempted Ololokwe’s main massif, which has seen serious accidents involving experienced MCK climbers. In 2018, a Kenyan climber broke both ankles and suffered multiple other injuries after a fall off pitch two of Not All Handholds (Are Your Friends) (HVS; FA: Jenny Tracy, Steven Brown, Duncan Francis, 2014). D’pa and the Samburu from Sabache were among the first on the scene, helping MCK members carry the injured climber down. It took 13 hours of hacking through thickets with a stretcher and a close encounter with a herd of elephants just to reach the tarmac.

The massif, as Wielochowski puts it, is “a bloody big monster”—committing.

Samson Mwangi became one of the few Kenyans to tackle it when in 2019 he managed the second known ascent of Mirage (SA 20 A2), a powerful line up the heart of the wall forged in 2014 by Alex Fiksman and Johannes Oos, a German climber who lived in the country for a time. Mwangi, who has managed the Climb BlueSky gym in Nairobi since 2018, is a tall, laconic climber with a touch of the wry masochism required for adventuring in the Kenyan bush. He called the wall a major undertaking.

“Everything I’ve learned came through for [that] one route. You forget about everything else,” he told me over the hum of the Nairobi gym. He described long runouts, a hanging belay off a single cam, and an emergency bivy in a pigeon hole. He feels that few Kenyan climbers are prepared for a climb of that scale yet.

“[The Samburu climbers] have a lot of potential … if they have someone who can mentor them,” Mwangi says. He has introduced the sport to hundreds of Kenyans, but says “few of them come back,” a pattern seen from the beginning: As Robert Chambers, now 93 and living in the UK, told me in an email regarding his partner for that first ascent, “Henry [Mwongela] did not go on climbing, [because of] family demands and obligations. Also, I dare say cost and vehicle issues.” The cost of equipment and, until recently, the lack of entry-level crags have made climbing a difficult prospect for most Kenyans.

But beyond that, bush climbing is not everyone’s cup of tea.

“With the ropes, you could go anywhere.”

Kenya’s climbing community has always been contentious: It’s formed of a patchwork of transients, locals, and hard climbers. Accessibility (or use of bolts) often bows in adherence to old-school ethics. It can be difficult for visiting developers to get their bearings. While the MCK tries to guide the issue, bolting often goes on quietly in the background as debates rage on Facebook. There is little consistency in hardware, style, or even grading. This tension is particularly salient in places like Ololokwe, where a budding local community needs safe, moderate routes to learn on—young Samburu climbers lack access to the transportation, equipment, training, or emergency resources that many new climbers have elsewhere. The Samburu rely entirely on whatever routes visiting teams establish and whatever gear has been donated.

Until recently, no one had thought much about mentoring the Ololokwe-area community members. According to the American expatriate Vadim Kuklov, one of Shah’s climbing partners, “Climbers of that era, British-Kenyans and expats, had no interest in getting to know or developing the capacity of local climbers.” Climbers comprised a fairly exclusive club.

After Ian Howell began exploring the area from the dusty outpost of Isiolo in 1967 while building communication systems for the Kenya Police, he and an early band of mostly foreign climbers, as Wielochowski recalls, “had access to the whole of northern Kenya, at a time when it was virtually unclimbed. In Kenya in the ’70s and early ’80s, bolting was a little bit frowned upon … but you saw these huge acres of rock where clearly there were no real cracks to follow.”

This vast, stunning acreage remained untapped until recent years. Since Fiksman and Oos opened a new era with the direttissima Mirage in 2014, new teams have put up modern mixed routes like the 13-pitch 100 Percent Not Losing (5.13a), established in 2017 on the east face of Mount Ololokwe by the American climbers Eric Bissell, Brittany Griffith, Kate Rutherford, and Jonathan Thesenga only a few hundred feet from the original attempt on the Oasis Wall.

Today’s visitors bring their own perspectives. “One of my favorite parts of going to these places,” Rutherford, of Bishop, California, says, “is showing up and saying, ‘Yeah, we did travel across the world to come to your piece of rock, because we think it’s beautiful enough to come this far for.’” Rutherford and Bissell described cooking dinner with their Samburu guides atop the massif, the savanna thousands of feet below fading in the twilight, learning from the moran how to start a fire with sticks and friction.

Such remote development is complicated; at times it is a boon to the local community, and at times a burden, an aspect climbers are trying to respect. “It’s just this wild experience of getting dropped into someone else’s life,” says Bissell. “You have this goal of climbing this route, [but] you aren’t just there to be a tourist. You can establish person-to-person connections.”

Rutherford and friends basecamped out of D’pa’s ecolodge where on their first trip, in 2016, the group saw a verdant, rainy-season Samburuland. However, upon returning in 2017, they found a region devastated by drought. “They were still super welcoming and psyched we were there,” she says, but she had mixed feelings: “It felt like we were taking their resources.”

Another concern in teaching the locals to climb is the introduction of risk. As Wielochowski says, the Samburu “rely on the young men to look after the parents and families, providing for them—not spend their time risking their lives on the mountain.” While foreign teams can come and go, most Samburu remain tied to the land.

Thus it’s crucial, says Kris Fiore of Vermont, who visited Ololokwe in early 2020 and with Luke Mendola put up the two-pitch Kivuli cha Mti wa Mwiba (5.11b), that would-be developers be on the “high and tight when it comes to quality of your hardware, quality of your techniques, knowing what you’re doing.” The goal, says Fiore, who traveled to Kenya with an American Alpine Club “Live Your Dream” grant, should be to establish routes the locals can also safely enjoy.

All things considered, the Samburu are learning fast. In December 2020, I joined Shah for a return visit, and he partnered me up with Ian Lekiluai, another of the moran.

Lekiluai, age 23, grew up in Lemata, a village that lies in the late-afternoon shade of the Ololokwe massif, less than a mile away. As a kid, he was the goatherd traipsing through the acacia and scampering up the gneiss slabs to chase baboons. Seven years ago, after the circumcision ceremony initiating Lekiluai as a moran, D’pa took the youth under his wing. Soon, Lekiluai was portering visiting climbers to the rocks he’d known since childhood.

“I saw these guys coming and climbing the same rocks, and I could see [that] with the ropes, you could go anywhere!” Lekiluai told me as our four-by-four rumbled down the dirt tracks leading to the Sabache community ecolodge.

At the practice boulder a quick walk from camp, we warmed up amidst a polyphony of birdsong. I topped out and watched Lekiluai make the last few moves with artful footwork, pausing suddenly and gesturing with his head: “The hornbills are dancing.” In the trees at eye level, two Jackson’s hornbills flirted, the male puffing up its chest and wings. “We Samburu are like the birds,” he said with a grin. “We grew up in the mountains, nature all around.”

Though Lekiluai and the cadre of Samburu mentored by Shah have little context for what lies in their backyard, they still climb 5.10 in secondhand shoes. They are social mavericks whose families cannot comprehend their choices, who jingle with jewelry and colorful Camalots, who moan about their fitness and shout exhortations in Samburu: “M’aape! (Let’s go!)” interspersed with “¡Venga!” and “Allez!” picked up from foreign climbers.

The emergent climbing culture has its challenges, however: The Samburu climbers as yet comprise a boys’ club. Many Samburu communities remain steeped in patriarchal traditions in which women have few to no rights. Girls may be subjected to illegal female genital mutilation/cutting (or FGM/C) in the belief that it will make them accepted and marriageable. Though FGM/C was prohibited in Kenya in 2011, many elders still adhere to the practice—a source of increasing tension with Samburu from younger generations like Lekiluai, who say the tradition is “unacceptable.” A variety of local and international organizations are on the front lines of this issue, a violation of human rights.

I’ve talked with some of the climbers about the roles of women within the Samburu culture, and found them reflective and open-minded, especially after gaining education and interacting with Western or Nairobi women. Early on, as climbing training began with Shah and Wielochowski, several women were invited. Participation with the all-male crew may have been too freighted, and they did not complete the trainings, but Wielochowki says they remain interested. Young Samburu women “want to compete with the boys,” said Lekiluai, who hopes more women will join in future sessions.

When I asked Lekiluai and his friends about seeing strong female climbers like Kate Rutherford and Brittany Griffith come to put up routes, they spoke in awed tones. As Lekiluai told me at the campfire one evening, “You realize there are women who can do everything you can, and more.” When my partner, Nicolle Richards, visited in December 2019, the moran cheered in camaraderie as she cruised the same routes they practice on. Visiting climbers can have more than one impact here, providing different perspectives to a culture in transition.

Climbing has also taken Lekiluai himself further out into the world: Just this year, he completed his diploma in travel and tourism from the Nairobi Institute of Business Studies. In Nairobi, Lekiluai began climbing with Samson Mwangi—and Lekiluai and Lemaiyan even competed in the gym’s annual bouldering competition, in which dozens of MCK friends who had visited Ololokwe over the years shouted encouragement and beta.

Our last day at Sabache, I set out with Shah and the spirited band of moran for a slender spire known as the Mouse, rearing 170 feet above the acacia thickets. At the base, we scrambled under a 5.12 bolted by Alex Honnold as he passed through on a North Face trip in December 2016, and in sight of a line by Cedar Wright and Maury Birdwell on the striking Cat formation just to the south (Samburu Direct; 5.12+ R; 5 pitches). Around the corner from these impressive lines, Lekiluai led the second pitch of the Original Route, aka the Mouse (5.10d), for the first time, muttering an all-too-familiar “Shit!” under his breath as the flakes creaked under his fingers.

Watching him move above the wild expanse he’d known since childhood, I was reminded of rock climbing’s capacity to connect. It’s hard to imagine a more disparate life experience from my own than that of Ian Lekiluai, and yet when we roped up together, I recognized the intent gaze that communicates We’re in this together. Shah, who watched Lekiluai swing leads with me, called the partnership a proud moment. “This place is becoming more popular—and it’s because of these guys.”

“We’re all climbers.”

Samburuland, teeming with wild bush spires, tiers of untouched crags, and 1,500-foot walls, could become a center for rock climbing: an activity that requires collaboration and connects individuals from every corner of the human experience. As the sport becomes more established, more localized, and more inclusive, it is crucial that the international climbing community seek the blessing and support of local communities like the Samburu to establish a sustainable and mutually beneficial future for climbing. At the same time, the complexion of climbing will continue to evolve, and new climbers like Lekiluai will seek out mentors like Shah, Wielochowski, and Mwangi. If codependency is the mark of the neocolonial world, perhaps interdependency is one response, particularly among climbers.

As Samson Mwangi told me: “We are all one. Climbing is for everyone, whether you are a strong climber or you are just starting—we’re all climbers.”

Kenyan Climbing 101

Ololokwe is merely the wildest frontier of a country teeming with adventure climbing. Two hours to the south towers Mount Kenya (17,057 feet), an unforgettable quest through the equatorial alpine with a robust climbing and cultural history. Hell’s Gate National Park, in the Great Rift Valley, cuts 600-foot basalt walls out of a sweeping savanna. Views include zebras and giraffes promenading across the valley floor as you stem up overhanging dihedrals and jam splitter cracks.

The prolific first ascentionists Iain Allen and Ian Howell developed a Hell’s Gate “seriousness” rating of 1 to 6 to quantify factors like rotten rock, vultures’ nests, and pure exposure. Having personally pulled on crimps that turned out to be festering vulture dung, I can attest to its usefulness. The few crags around Nairobi (such as the gneiss cliff of Lukenya) see increasing traffic, but give only a taste of the country’s potential.

All requests for beta or potential development should be run through the Mountain Club of Kenya (mck.or.ke). The country’s lively climbing history is sparsely documented and its community is watchful, so follow Fish Shah’s example and build relationships with the locals, via the MCK, before you wield your drill.

James Farr (@kileleproject) learned to climb in the crags around Nairobi as a teenager, and now works as an experiential educator at a wildlife conservancy a few hours from Ololokwe. True to his roots, he prefers his climbing desperate and dirty.

For more information on FGM/C, visit orchidproject.org.