The Warriors' Walls

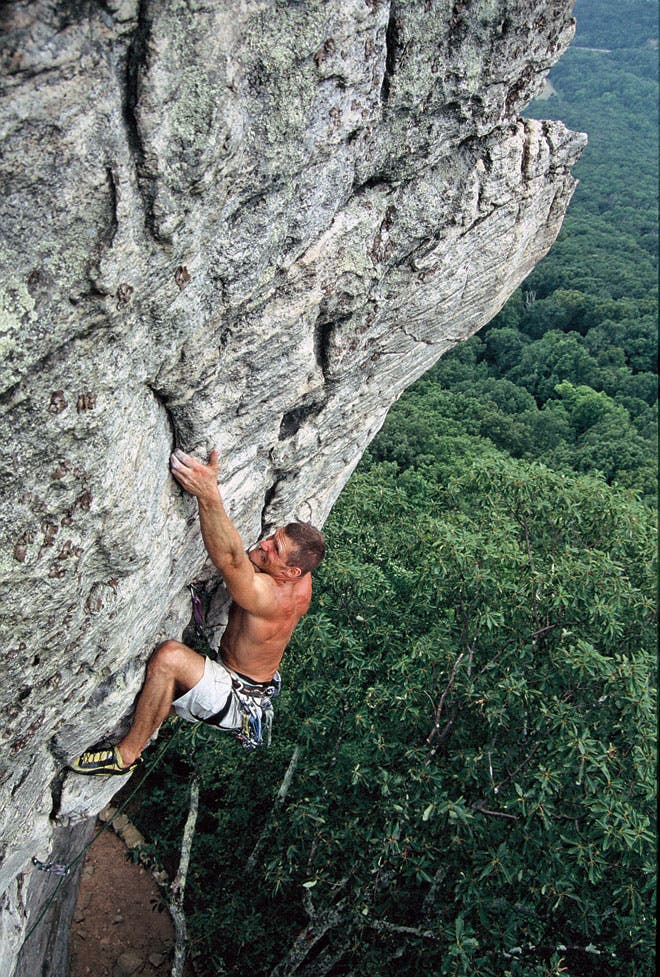

"Great-Gig-in-the-Sky-Cochise-660"

From Bunker Hill, Gettysburg, and Belleau Woods to Normandy, Inchon, and Fallujah, the United States military has written a distinguished history on battlefields. But one thing it hasn’t traditionally done well is climb. For the last 60 years, civilian climbers have rightly considered military climbing methods to be nothing short of ridiculous. Watching American soldiers endure training for mountain and technical climbing is often hilarious, when it isn’t downright frightening. During my time in the Army, from 1984 to 1992, I witnessed entire units tie into harnesses constructed from strands of rope, called “Swiss Seats,” finished with square knots. Most instructors couldn’t equalize an anchor, and during rappels, antiquated Goldline rope whizzed through non-locking steel carabiners manufactured during the Eisenhower administration. In ascent, soldiers heaved themselves upward, belly-flopping on the rock, combat boots greasing off footholds the size of bivy ledges.

But they have made much progress: Specialoperations teams have adopted up-to-date, “civilian” climbing techniques and gear in the last two decades, and those techniques are filtering down to regular units. Training military units to climb is difficult; many soldiers don’t enjoy the sport. It’s important for civilians to recognize that the military isn’t trying to have fun—it’s trying to teach skills that might help win a war. (I know firsthand: I served four years as a light infantry platoon leader, and I did my first rappels under the stern gaze of an Army sergeant at Camp Buckner, New York.) The military’s efforts also benefit climbers in a little-known way: A number of popular American crags once served as training grounds or battlefields. Here are some of the best.

Mt. Yonah, Georgia

In 1960, the U.S. Army Ranger School chose a 200-foot granite eyebrow near the top of 3,166-foot Mt. Yonah in northern Georgia’s Chattahoochee National Forest as the site for its technical climbing instruction. They promptly cleaned off the loose rock, covered the crag with bolts and steel cables, and spray-painted colors and numbers all over the main cliff to identify various routes.

Ranger School currently bases its 18-day “mountain phase” at nearby Camp Merrill, where Ranger candidates learn “military mountaineering tasks, mobility training, as well as techniques for employing a platoon for continuous combat patrol operations in a mountainous environment,” according to the Ranger School’s official statement. The course consists of only four days of actual climbing training: two days on the ground learning knots, belays, anchors, rope handling, and climbing and rappelling fundamentals, and two days of real climbing and hauling. Today’s equipment mirrors civilians’ gear, only with a military touch of camo and a few other modifications. Paint and bolts from the ’60s still mar the face, but nowadays the Rangers maintain and update anchors, and take part in trail and campsite clean-up projects.

There’s plenty for “civvy” climbers, too. Mt. Yonah offers dozens of easy to moderate routes on high-quality rock. Located about 1.5 hours north of Atlanta, and just a few miles north of Cleveland—named for a general in the War of 1812—Mt. Yonah offers slabby friction, steep jughauling, and even a few cracks. There are more than 40 climbs on the Main Face, and several dozen others on surrounding crags. Dihedral, a two-pitch 5.6, is a common first lead for aspiring trad climbers. The overhanging layback crack on the area classic Stannard’s Crack, a 5.8 put up in 1972 by Seneca Rocks legend John Stannard, has a crux most consider to be 5.9+. Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds (5.10a) tests your balance with thin face climbing.

For beginner climbers, the Army’s ample anchors and cable systems make topropes easy to rig. There is also plentiful bouldering scattered all over the mountain, with the most popular area only 200 yards from the parking lot. But be warned: Rangers still train here a few times a month, and when they do, you’ll have to work around the green horde dominating the cliff.

-

Season: The Main Face orients southwest and can be too hot on summer afternoons; however, surrounding areas receive more shade and are enjoyable in warm weather.

-

Camping: Follow the directions for the main trail, and pass the trail that branches off to The Boulder. Continue another 300 yards to intersect with the old Forest Service road. Turn right up the road for 100 yards to a large camping area in the saddle. No amenities.

-

Guidebook: The Dixie Cragger’s Atlas, by Chris Watson (dixiecragger.com)

-

Rack: Bolts line many routes, but trad lines are also abundant. Bring a standard rack and 60m rope.

Seneca Rocks, West Virginia

In the 1940s, at the height of World War II, elements of what is now referred to as the 10th Mountain Division detached from Camp Hale, Colorado, to begin training on the sky-scraping fins of sheer Tuscarora quartzite at Seneca Rocks; this region resembles the mountainous terrain of Italy, so soldiers could prepare for their eventual battlefield successes in these hills. Back then, Seneca was part of the West Virginia Maneuver Area, a military training ground spanning five counties. Several thousand soldiers learned the rudiments of climbing in the area, and before the war ended with the surrender of the Axis powers, the Army hammered in more than 75,000 soft-iron pitons. Over the last 60 years, most of the pins have fallen out or been removed, but the South Peak of the West Face has been christened the “Face of a 1,000 Pitons.” Today, it’s common to spot remains of the Army’s piton fetish throughout the area.

The siege of recreational climbers didn’t begin in earnest until about 15 years later. Triple S (aka Shipley’s Shivering Shimmy; 5.8) was established in 1960, then the area’s hardest route, and it’s still one of the finest pitches on the East Coast—make sure your calves are ready for sustained stemming. Overall, Seneca has a reputation for stout lines and stiff grades, but there are routes for every climber. In fact, due to the high number of 5.easy trad routes, Diane Kearns, owner of Seneca Rocks Climbing School, says it’s a great crag to target for a first trad lead. More than 400 routes blend face climbing with crack techniques on dead-vertical stone.

Most climbers improperly credit the classic Conn’s West (5.4) to the legendary pioneering duo of Herb and Jan Conn, but it was the Army—specifically N.C. Hartz, Henry Schulter, and Earl Richardson— who made the route’s first ascent in 1944. A two-pitch adventure up a left-facing dihedral, through a chimney, and a right-facing corner, Conn’s West is one of the Army’s proudest noncombat accomplishments. Many other easy routes sport military origins, such as Pooh’s Corner (5.1) and Heffalump Trap (5.3) on the East Face of the North Peak. Seneca’s civilian-pioneered classics include the three pitches of Ecstasy (5.7), the twin 5.10a thin cracks of Pollux and Castor, and the fine effort of Herb Laeger’s 1975 first ascent of the sustained Terra Firma Homesick Blues (5.11).

-

Season: April to October.

-

Camping: Seneca Shadows Campground has a great view of Seneca Rocks and is equipped with flush toilets, picnic tables, and fire rings, and 40 tent sites. Reservations required; $13–$20 (recreation.gov). Yokum’s Vacationland offers tent sites, along with cabin rentals and a motel. Camping is $6.50 per person, no reservations required (yokum.com).

-

Guidebook: Seneca: The Climber’s Guide, 2nd Edition, by Tony Barnes (earthboundsports.com).

-

Rack: Standard rack, 60m rope.

Cochise Stronghold, Arizona

Eighty years before the 10th Mountain division tackled the steeps of Seneca and conquered Riva Ridge in Italy, the U.S. Army faced a different breed of mountain warrior in the central Dragoon Mountains of southeastern Arizona: the Chiricahua Apache. Holed up in a nearly impregnable sanctuary among the maze of towering domes and rugged canyons of Cochise Stronghold, Chiricahua warriors, led by their great warrior chief Cochise, attacked the surrounding countryside throughout the 1860s and early 1870s, raiding miners, ranches, and stagecoaches. The U.S. Army fought back, but it couldn’t penetrate Cochise’s stronghold; Apache lookouts atop the tall sentinels could spot Army units approaching from miles away.

The lethal conflict lasted a dozen years, but the grinding might of the U.S. Army gradually hemmed in Cochise and his people into ever-smaller sections of the sanctuary, eventually denying them access to adequate food. Below the crags of his garrison, the chief negotiated his surrender to the Army in 1872. Shorn of his freedom, Cochise died two years later. Considered among the greatest of Native American warriors, he is buried somewhere among the Stronghold’s majestic spires—the Chiricahua never revealed the exact location.

The coarse granite routes here weren’t developed by the military, but they are steeped in Army history. A route development boom took hold in the 1970s, and climbers now flock to routes lined with flakes, positive edges, and chickenheads. Best known for traditional multi-pitches up to 900 feet long, the Stronghold also offers single- and multi-pitch sport climbs, though many of the bolted routes require occasional gear.

For quintessential chickenhead fun, set out on the six-pitch Moby Dick (5.8). Or head to the steep, exposed, and highly recommended Wasteland (5.8), zig-zagging up through chimneys and chickenheads. For sustained quality, try the first pitch of Forest Lawn (5.9+): steep laybacking in a left-facing corner. Or dig into your quiver for the varied Abracadaver (5.11a), whose moves vary from offwidths to laybacking to slab climbing.

-

Season: Spring and fall are best, but you can climb in the winter on sunny days; highs often reach 60.

-

Camping: The Cochise Stronghold Campground in the East Stronghold is open from September 1 to May 31; $10 per night. (fs.usda.gov). There are also free sites on the west side of the Dragoons at the end of the access road.

-

Guidebooks: Backcountry Climbing in Southern Arizona, by Bob Kerry, is out of print, but you can read the book’s contents on climbaz.com; Rock Climbing Arizona, by Stewart Green (falcon.com)

-

Rack: Standard rack, 60m rope.

Sunset Rock, Tennessee

During the Civil War, Chattanooga was the crucial piece of military geography between Virginia and Mississippi. In the fall of 1863, after their disastrous defeat at Chickamauga Creek, Union forces led by Ulysses S. Grant were trapped in the city. Confederate general Braxton Bragg laid siege to the town, his positions anchored on Missionary Ridge and the formidable Lookout Mountain to the southwest, which was occupied by about 4,500 of his men.

On November 24, 1863, Union soldiers attacked the Confederates holding Lookout Mountain. Knowing a frontal assault would fail, the 10,000 men swept across the western slopes of the ridge, directly below the Sunset Rock we climb today. Union soldiers advanced quickly, a thick fog stifling the sounds of their movement. In the mid-morning, blue-coated Federals loomed out of the fog, bayonets fixed, and surprised the Confederate outposts. Outnumbered, the Confederate positions collapsed.

The Union drive scoured the flanks of the mountain to its north end, where the attack faltered against a rebel reserve. A reinforced second assault carried the Federals forward; fighting raged through the evening, killing or wounding nearly 600 men.

The Rebels held long enough to evacuate the threatened units, but sunrise dealt the Confederates a massive blow: the sight of the United States flag fluttering from the summit of the supposedly impenetrable mountain. That afternoon, in one of the most stunning attacks of the war, the main strength of General Grant’s army drove the Rebels from Missionary Ridge, blasting open the gateway to the Deep South.

Today, Sunset is part of the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, with whom the Southeastern Climbers Coalition has built an excellent relationship to preserve climbing on the more than 250 routes at two sectors: Sunset South and Sunset North. The grades are stout, and the routes demand a gamut of techniques: roofs, hand and finger cracks, flakes, jug hauls, and crimpy faces. You’ll often find all of these on the same route.

Start at Sunset South and warm up on the aptlynamed Jug Mania (5.7) and Afternoon Delight (5.7+); the latter’s crack system will get your blood pumping for a right-facing dihedral and steep crack on the two-pitch Northwest Conversion (5.9). End the south-end tour on the finger crack and roof finish on Silent Runner (5.10a). At Sunset North, sink hand jams in the corner on Stan’s Crack (5.8), and then hop on Rusty’s Crack (5.10a/b), which the guidebook says, “still stumps the best of climbers.” Test your prowess on the bulging arête of The Prow (5.11c/d) and the utterly classic testpiece Jennifer’s World (5.12a/b).

The crag and the military park are in a residential neighborhood; be courteous and leave the climbing area before sundown. Parking at Sunset is extremely limited; other options include parking at the Point Park ranger station or Chattanooga Nature Center at the foot of Lookout Mountain. Please consult the guidebook for all regulations.

-

Season: Sunset faces west and stays mostly in the shade, providing a nice summer crag. Winter can be too chilly.

-

Camping: There is no camping at Sunset. Head to nearby Tennessee Wall (also in the guidebook) for free sites, or check out the Crash Pad, a hostel in downtown Chattanooga. (crashpadchattanooga.com)

-

Guidebook: The Dixie Cragger’s Atlas, by Chris Watford

-

Rack: Standard rack, 60m rope.

Rock Camp: a brief history of other military crags

In 1942, the U.S. Army began constructing Camp Hale at 9,250 feet in the Colorado Rockies. By 1943, about 14,000 soldiers were based there, training in rock climbing, skiing, and cold-weather survival, and they went on to use these skills in battle in Europe. Following the war, veterans of the 10th Mountain Division were instrumental in creating the modern U.S. ski industry; their ranks also included well-known climbers like Fred Beckey and Paul Petzoldt.

You can still climb on the crags where these soldiers learned the ropes. The high-angled slabs at Camp Hale hold a selection of bolted climbs from 5.7 to 5.12, and the nearby crags of Homestake and Hornsilver have some excellent sport routes.

After World War II, the knowledge and equipment of the 10th Mountain Division spread across the country. Army climbers from Fort Carson in Colorado Springs, Colorado— now also home to Peterson Air Force Base—used the soft-iron pitons so infamously used at Seneca Rocks to climb on the colorful sandstone of Garden of the Gods, earning credit for such first ascents as the North Ridge (5.7) of Montezuma Tower, The Three Graces formation, and West Point Crack (5.8) on South Gateway Rock. That last route calls to mind the Military Academy in West Point, New York, where for the last 30 years, the Cadet Mountaineering Club has developed a slew of modern cragging, most of it under the direction of “Gnarly” Ned Crossley, a now-retired physical education instructor. Unfortunately, the best climbing at West Point is “on post,” thus difficult for civilian climbers to access. Even more classified is buildering on the granite blocks of West Point’s massive barracks and academic buildings, most of which is off-limits even to the cadets. Watching Cadet Todd Nicholson stem, chimney, and hand traverse—an onsight, solo first ascent—into the window of his room on the fifth floor of MacArthur Barracks in 1986 still ranks as one of the boldest climbs I’ve witnessed.

Nowadays, some special forces units train at the Sierra Rock Climbing School in Bishop, California, which offers a six-day Military Climbing Program. The program teaches rescue training, anchor building, and lead climbing. “They’re looking to be self-sufficient,” says Zeke Federman, president of the school. “They want to be able to go out to the middle of the mountains in Afghanistan and deal with the technical aspects on their own.”

Gregory Crouch graduated from West Point in 1988 (where he was Cadet-in-Charge of the Cadet Mountaineering Club) and from Ranger School in 1989. He served four years in the 7th Infantry Division. A former Senior Contributing Editor of Climbing, he is the author of Enduring Patagonia and the true-life World War II flying adventure China’s Wings.