Under the Devil's Spell

"Peter-Vintoniv-McCarthy-North-Face-660"

Every climber should scale Wyoming’s iconic Devils Tower at least once in his life. Frank Sanders has 2,000 ascents and counting. He’s as comfortable 150 feet up the east face of Devils Tower as he is in his own house. Which is appropriate, because he’s probably spent more time on the Tower than in his living room.

“I don’t know about you, but I think I just saw a 60-year-old man walk up this shit,” Frank calls to Hanna Derby, his 20-year-old summer intern, from the first belay on Soler as she battles up the first pitch. Hanna had never climbed before she visited Devils Tower with her parents a few months ago, and now Frank is leading her and me up this classic two-pitch 5.9, a straight-up crack in a right-facing dihedral.

Frank did walk up it. I watched him place one piece of gear in the first 40 feet of 5.8 as it gradually steepened, stemming and smearing in an old, blown-out pair of pink Five Ten Anasazi Lace-Ups. He paused only a handful of times to place more gear as he sailed up the rest of the pitch. I struggled following the second pitch, my fingers locked in the crack, my feet skating off the face where Frank walked up a few minutes ago. The day before I asked Frank (who’s climbed Soler at least 100 times), “Is it true everything on the Tower is pretty sandbagged?” He acted like he didn’t hear me.

Devils Tower is a curiosity for many tourists making their way across Wyoming. The eerie, 85-story corrugated column pops out of the skyline from the prairie, its blocky columns and dihedrals rising to a flat summit. You’ll find pure, sweeping crack climbs, with only a handful of bolts on the entire formation. Novice trad climbers show up here to tackle the “50 Classics’” Durrance route, universally considered sandbagged at 5.6 or 5.7—sometimes now rated 5.8—and others are drawn here by a photo of a climber spread-eagle in the 130-foot stem box on the second pitch of El Matador (5.10d), maybe the most famous pitch on the Tower. Some get served on the stout cracks and hit the road, but some get hooked and keep coming back. Some, like Frank, never leave.

Frank, a climbing guide and bed-andbreakfast proprietor, does not speak; he orates. He talks to you as if you are a room full of people. He has 1,001 stories and statistics about the Tower, its climbs, and the world surrounding it. He will play “Desperado” on the piano in the living room of the Devils Tower Lodge, where his guide service, Devils Tower Climbing, is based. He will tow anyone up just about any climb, while he smokes Camel Filters at the belays and coaxes you up with advice like, “Walk when you can, climb when you have to.” Frank is 62 years old, and even if you’re half his age, he will outclimb you; he’ll out-charm you, too, with a smile from under his white handlebar mustache. He hitchhiked here in 1972 from Washington, D.C., to climb the Tower, getting here in the middle of the night.

“We arrived in a heatlightning storm, and the closer we got to the Tower, the more it looked like Dracula’s castle,” Frank says. “My first glimpses were where the lightning flashes illuminated it.” The next morning, Frank thumbed to the formation and climbed Durrance with the Bailey Direct finish.

Frank has summited the Tower more than 2,000 times since. In a little more than a year, from 2007 to 2008, he topped out 365 times, missing only five days because he threw out his back. His personal record is 16 summits in one day—15 of those free solo, for no particular reason. (“The juice was flowing,” he says.) He’s had a hand in putting up almost a third of the more than 200 routes here, from first ascents to first free ascents to aid routes. Frank has climbed all over North America, starting on the East Coast and heading West in his early 20s (including 21 El Capitan summits), but he kept coming back to northeast Wyoming.

“I’d like to say I’m in love with Devils Tower and its climbing, but that’s not even half of it,” Frank says. “I’m in love with the pace and the style and the form of life here. And the land. We have no stoplights in this county. We have 44 people in our ZIP code. My nearest neighbor is three miles away, and his nearest neighbor is two miles farther down the road. We have fewer than 5,000 people in the county, and less than half a million people in the whole state.”

Devils Tower became America’s first national monument in 1906. This igneous intrusion, one mile in circumference, rising 867 feet from its base to its 1.5-acre summit, drew the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt and thousands of visitors every year, and especially the curiosity of a few explorers, some a bit misguided. In 1893, local ranchers William Rogers and Willard Ripley first stood atop the Tower after pounding a wooden stake ladder into the cracks on the south face, still visible today.

Legendary hardman Fritz Wiessner put up the first legitimate climbing route to the summit in 1937, the 5.7 Wiessner. Climbers today—aware that the 5.7 rating is stout, to put it lightly—will advise taking a #5 or #6 Camalot to protect the wide second pitch. Wiessner himself placed one piton on the entire climb, and regretted it afterward. The trade route to the summit, Durrance, went up in 1938, and it’s a full-value, oldschool grunt-fest: offwidth, face, crack, stemming, and the “Jump Traverse” at the beginning of the final pitch to the Meadows, which is a flat section about 120 feet from the summit. It’s not a good place to learn to stem or climb offwidths, as many beginning leaders find out on all-day miniepics there—and as I did my first time here in 2008. My partner never climbed again.

In 1941, parachutist George Hopkins landed on top of the Tower, and his plan to lower himself off with a 1,000-foot rope dropped from a plane failed when the rope bounced off the summit and fell partly down one side, hanging in a giant tangled mess. He sat atop the Tower for six days, until Jack Durrance led seven other climbers to the summit to rescue him. A stream of gawkers, reportedly topping 7,000 people, showed up to see Hopkins marooned atop it.

Climbing on Devils Tower has, in the past 20 years, become a controversial topic. More than two dozen Native American tribes have cultural and spiritual ties here, with varying stories, legends, and names for the Tower: Bear’s Lodge, Bear’s Tipi, Tree Rock, and more. Several tribal ceremonies involve the edifice, and prayer bundles and cloths are often found at the base. In 1995, a voluntary June climbing closure was created in deference to the spiritual significance for those tribes. Still, some folks find climbing on the Tower sacrilege. Frank points out that the Tower is a national monument, and he considers climbing it to be his form of worship.

“You can’t legislate reverence,” Frank says. “Nobody’s up there with neon lights flashing. Everyone shows more than their share of respect and reverence for this place. Maybe some climbers don’t see beating loud on tom-toms as showing reverence. That’s OK, some do. Some of the natives don’t think that climbing up and down the Tower is showing reverence. Well, until they go climbing, they don’t understand what a spiritual experience climbing is.”

Frank has taken members of the nearby Pine Ridge Reservation climbing on Devils Tower a couple dozen times. A few have done it as a religious observance, but the majority just want to see what it’s like. Having guided hundreds of people to the summit, Frank is arguably the Tower’s biggest evangelist, religious or otherwise. We top out and stay on the summit chatting until the sun begins to set, painting the Belle Fourche valley a glowing gold a thousand feet below. As we walk across the dark parking lot at the base, a guy who had watched us rappel approached and asked Frank if there were any good 5.7s up there. I smiled under the light of my headlamp as I heard him say the magic word— “sandbagged”—and warn the guy that a 5.7 here would easily be a 5.8 anywhere else.

“But if you’re doing it right,” Frank says, “you don’t hold onto the rock. The rock holds on to you.” And in some cases, the Tower does, too.

Frank Knows: Solid advice on…

Grades “The first thing you need to know is that the first routes here were done by East Coast people. And if you haven’t visited the East Coast, you should know that eastern grades are much stiffer than West Coast grades. What we have here at Devils Tower is this little island of East Coast grading. And the first two first ascensionists, Wiessner and Durrance, were also humble. Mr. Wiessner conservatively rated his climb (Wiessner) as 5.7 or 5.8, and Mr. Durrance in his humble way said, ‘Well, mine’s easier than that, so it’s gotta be 5.6.’ Don’t be fooled. If Mr. Durrance’s route is indeed a 5.6, it’s a 5.6d. One guidebook rates it at 5.8, but knowing the guidebook author, the reason he did that was to keep people from feeling sandbagged. Don’t be put off or get misled by the numbers. 5.6 here is not a gimme. Start a grade easier than what you would normally feel comfortable climbing.”

Ropes “Bring two. Out here on this tower, where there’s a crack every six feet, there are lots of places to get your rappels hung up. If you have one rope and you get it hung up, you’re in a world of hurt. If you have two ropes and you get one of them hung up, you’ve got a chance to get down. I’ve been in on more Park Service rescues and assists than anyone in the history of Devils Tower, and most of them include stuck rappel ropes. So please, for the love of God, bring two ropes. Sixty meters is adequate; 70 is better.”

Gear “This is not Indian Creek. You don’t need 12 of one size. You need a good double rack of gear. Just be prudent with it. And get ready for some of the best crack climbing you’re ever going to walk into in your life.”

The Sanders 17: Frank’s favorite routes from 5.7 to 5.11

5.7 to 5.9

- Wiessner (5.7) 3 pitches, South Face: “Fritz Wiessner was small, but his heart was big, and his balls were even bigger. It’s a bold route. Unless you’re taking a bunch of tubes or No. 6 cams, it’s not very well protected. Fritz climbed it with a single piton. One of those soft-metal European ones that he hammered into a horizontal crack, well above the hard part. He basically climbed the hardest of the offwidth pitch absolutely free solo. I mean, he had a rope trailing hopelessly from his waist, but that was it. He didn’t know what was coming up, you know? That shows persistence, fortitude, focus, and desire.”

- Durrance (5.7) 4 pitches, South Face: “Shorter pitches, bigger ledges, more moderate climbing, better protection [than Wiessner]. Wiessner and Durrance are the two big classics.”

- Bon Homme, Horning Variation (5.8) 3 pitches, South Face

- El Cracko Diablo (5.8) 2 pitches, West Face: “It was established in 1973 by two ‘Minne-snow-ta’ folks, Pat Padden and Rod Johnson. It’s longer pitches of solid rock and obvious jams.”

- Patent Pending (5.8) 2 pitches, North Face: “If you like ’em wide, try this 5.8. After a little roof at the bottom, it’s about two and a half miles of offwidth.”

- Soler (5.9) 2 pitches, West Face: “Soler was the first aid climb on Devils Tower, established by Tony Soler and some of his Gunks friends in 1951. It was also the first aid climb to get free climbed when Layton Kor came along eight years later. If you can carry the rack, you can put in a piece of protection every three feet.”

- Walt Bailey Memorial (5.9) 2 pitches, Southeast Face: “Albeit a shorter climb, this was an aid route, and it got freed in the early 1970s. It’s a beautiful splitter that goes everywhere from fingertips to cupped hands. And just like an étude, or any other exercise you do: Whatever your weak size is, you’re gonna hit it. So the route works you like a tutor.”

- Assembly Line (5.9) 2 pitches, North Face: “The crux is a little fingers section at the bottom, but the bulk of the long, lovely second pitch is hands and more hands in a corner. If you’ve got your hand jams down, it’s 5.7. If you don’t, it’s 5.11. That’s why it’s rated 5.9. Every spring, I’m quick to get on Assembly Line, to get my meter tuned and see how I’m climbing. Because if it’s hard, well, you’ve got some work to do. But if it does feel like 5.7, you’re gonna be climbing some good cracks the rest of the season.”

The 5.10s

“You know that old saying, ‘the harder you climb, the more you can climb’? Well, if you can lead 5.10, a wide world of classics opens up to you here.”

- Tulgey Wood (5.10a) 2 pitches, West Face: “Each of the West Face climbs contains only one pitch of 5.10, and a lot of high-quality 5.9 free climbing. And all of these take you up the very tall and seemingly blank west face of the tower. These are all good routes to start very early in the morning—and see if you can get up to the top before the sun starts illuminating the face.”

- New Wave (5.10a) 2 pitches, North Face

- Burning Daylight (5.10b) 2 pitches, North Face

- Belle Fourche Buttress (5.10b) 4 pitches, North Face

- McCarthy West, Free Variation (5.10b) 5 pitches, West Face

- One-Way Sunset (5.10c) 4 pitches, North Face The 5 .11s

- Mr. Clean (5.11a) 2 pitches, West Face: “In 1977, to the locals’ great chagrin, ‘Hot’ Henry Barber came from the East Coast and established the Tower’s first 5.11. He was here last summer, and he showed us the six pieces that he used to protect that 5.11 pitch. It’s fingers and hands, no trick moves—just keep on jamming for the long haul. That train needs to keep a-runnin’ all night long, too.”

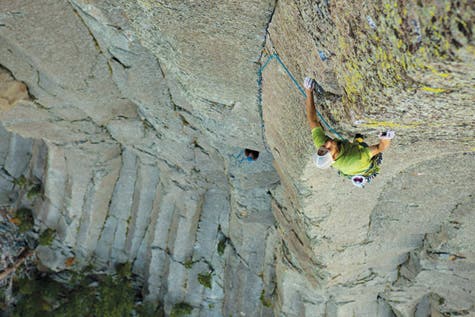

- McCarthy North Face (5.11a) 2 pitches, North Face: “It gets steep on the second pitch. It starts with a pull over a roof, and a tips crack that actually widens to fingers—grudgingly—by the end. It was established by two local folks in the spring of 1978: Dennis Horning and a wank named Frank [Sanders].”

- Carol’s Crack (5.11a) 3 pitches, North Face “After a 5.10a warm-up pitch, there’s a beautiful corner to stem, jam, smear—tips almost all the way. You can put in a piece every three feet, and the rack ain’t hard to carry—just small stoppers in keyhole placements. Most people don’t even use quickdraws— they rack nuts individually on single biners and drop ’em in. Take three #3s, four #4s, and five #5s, and some bigger stoppers, too.”

Road trip

Ticked the Tower! Now drive on for more rock.

+1.5 Hours: More than 600 steep limestone sport climbs, predominantly 5.10 to 5.13c, line Spearfish Canyon two miles south of the town of Spearfish, South Dakota, 90 minutes from Devils Tower. Resource: blackhillsclimbingguide.com+2.5 Hours: In the southern Black Hills, 2.5 hours from Devils Tower, get everything from sticky pegmatite granite bouldering and sport climbing to ballsy, old-school trad at Custer State Park and Mt. Rushmore National Memorial. Resources: extremeangles.com (Custer State Park); fixedpin.com (Mt. Rushmore)

Beta

- Get there: Devils Tower National Monument is 27 miles northwest of Sundance, Wyoming. You can’t miss it.

- Stay there: Target one of the 50 first-come, first-served campsites at the Belle Fourche Campground inside the monument ($12/night). Guidebook: Devils Tower Climbing, by Zach Orenczak and Rachael Lynn ($35, extremeangles.com)

- Guide service: Devils Tower Climbing, (307) 467-5267, devilstowerclimbing.com Contact: (307) 467-5350, nps.gov/deto