Chasing the Spirit of Fred Beckey

Chattanooga local Jared Leader redpoints the stunning pitch six during the first free ascent of the decades-old aid line The Illness (V 5.11) in the Wolverine Cirque of Wyoming’s Wind River Indian Reservation. (Photo: Bryan Miller)

This feature originally appeared in Climbing #378, published in Summer 2021, and was originally entitled “Chasing the Winds.”

The summit crest burned red in the dawn light 10 pitches overhead. Shadows cloaked the base of the wall as we shivered and racked for a final push. With bellies full of beef ramen and espresso Gu, we had hiked up from a bivy in the talus field, our bodies depleted after a sleepless night of lightning storms.

For Heath Rowland, my frequent-flier Southeast adventure partner; Jared Leader, a good-as-gold friend and Chattanooga, Tennessee, local; and me, the summer of 2020 was our second season of trying to free The Illness (V 5.10- A2+), a forgotten aid route deep in the Wind River Range, Wyoming, established over two decades ago by a team that included James and Franziska Garrett and Fred Beckey, who at age 76 still had an eye on the prize after six decades of plumbing the continent’s ranges.

By the fifth day working the route we had a familiarity in the routine: quickly free the easier first three pitches, jug fixed lines through the middle, and then work the upper ropelengths. The mad-dash effort left us breathless and cottonmouthed, but deposited us at the toe of pitch eight in less than two hours. There, at a small stance, I gulped water to ease the pain in my throat as I contemplated my lead: a steep offwidth to an overhanging boulder problem, then a delicate 5.10 dance over styrofoam rock, the only bad stone on the route. I’d freed the pitch the day before, negotiating hard moves above questionable gear, and had sworn that I’d never lead it again. But we’d used up all our fixing rope on the lower pitches, so here I was once again, tied in to battle the “Hateful Eighth.” The summit rim beckoned just 300 feet away.

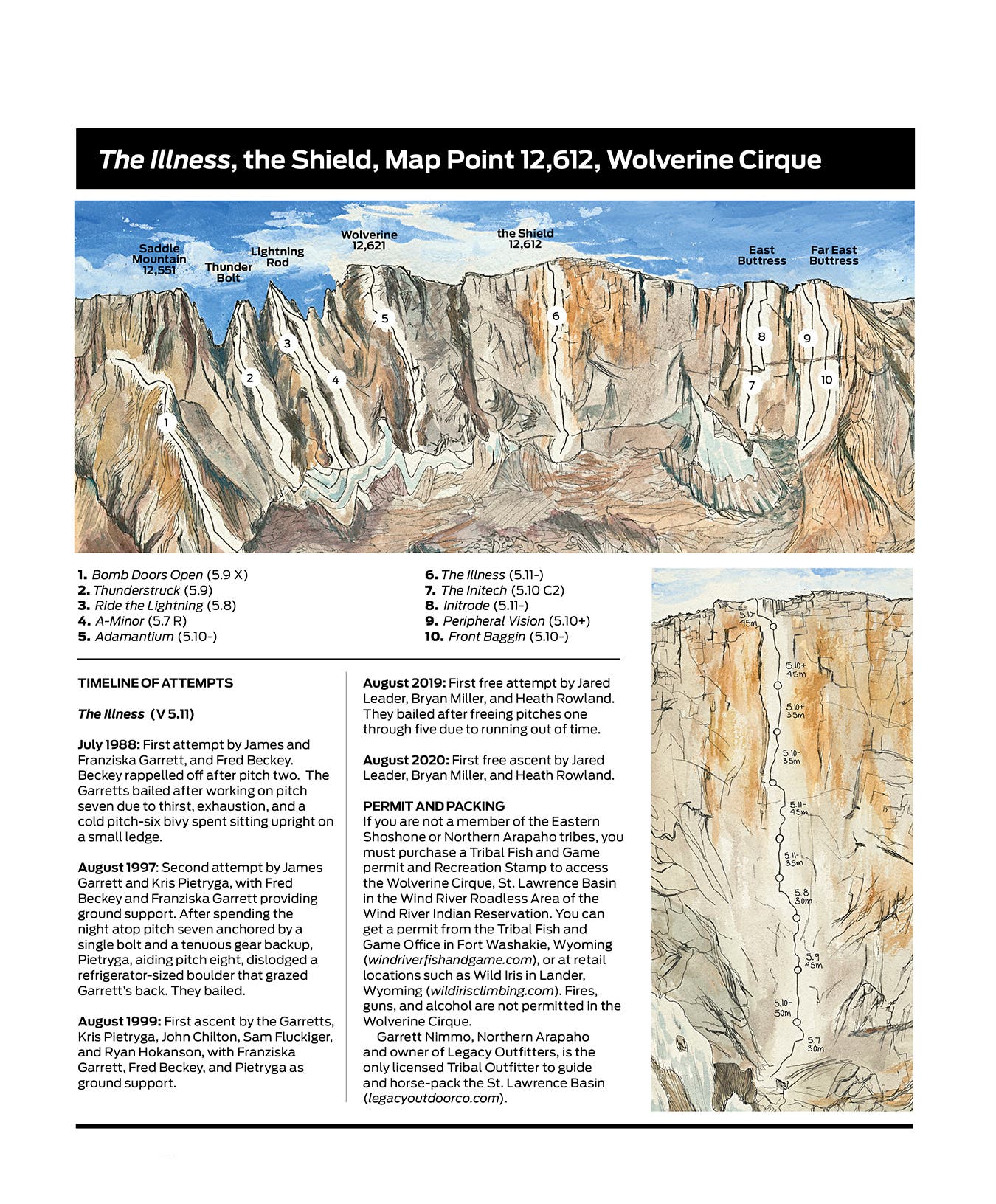

The Illness lies within the Wilson Creek drainage of the Wolverine Cirque in Wyoming’s Wind River Indian Reservation, home to Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes. The 2.2-million-acre reservation on the east side of the Winds may be the seventh largest in the country, but what remains is just five percent of the 44 million acres allocated by treaty in 1863, a stark reminder of Manifest Destiny’s land grab and subjugation of this country’s original people. Today, access is by tribal permit only, and few climbers ever venture here, preferring the Winds’ more accessible and developed areas like the Cirque of the Towers.

The Wolverine Cirque itself is an amphitheater of rough-cut granite peaks guarded by thigh-burning ridges of unsorted glacial till and miles of gnarled, stunted trees. Major cirque formations include Saddle Mountain (12,551 feet) to the southeast and Wolverine Peak (12,621 feet) to the northwest, with several minor peaks radiating north. But to my eyes no mountain stood out like “Map Point 12,612”—a Wolverine Peak sub-formation of starkly lighter granite, with a wall roughly 1,300 feet high and 1,500 feet wide. Ruled by clean architectural lines and a smooth face, the “Shield” is a grand wall, and The Illness bisects it like an expansion joint in concrete.

We weren’t the first climbers drawn to the Shield. In July 1988, Fred Beckey cruised into Lander with a carload of dirtbag stench, worn topos, and rubber-banded notecards gathered over a lifetime of climbing. In town, Beckey called James and Franziska Garrett, a couple from Salt Lake City, both working in the medical field, and serial Beckey climbing partners, to convince them of the cirque’s potential. Beckey had a nose for classic alpine routes, and the “tight lines on the topo map were pretty impressive,” Garrett says.

The three were soon on an unmarked dirt road north of Fort Washakie. Equipped with a map, compass, and altimeter, they hiked 13 miles, Beckey in his customary Norwegian-welted boots, all three lugging 100-pound packs through unknown territory. “I still hurt thinking about those damned packs,” says Garrett, and Beckey, then 65, “insisted on carrying an aid hammer, worn to a nub, secured to his hip with webbing.”

After a two-day approach, the trio could see what would become The Illness from miles away. “We were in awe,” says Garrett, “but we needed to climb something less intimidating first.” So, they established the North Ridge of Saddle Mountain—a beautiful, 1,800-foot 5.8+, a route Garrett remembers for its quality stone and for getting Beckey’s brand-new, and only, flexible Friend stuck halfway up. It was a loss that tormented poor Fred.

Descending via Saddle’s less-technical south side as the sun set, Beckey fell behind the Garretts, who, noting that the remaining 700-foot descent to camp was obvious, pushed on through talus and snow to prepare dinner and await Beckey’s arrival. However, hours passed without his return. The Garretts searched until nearly midnight before finding Beckey burrowed under a boulder, rope wrapped around him for warmth, his pack emptied and half pulled up his body. “I don’t move when it gets dark,” said a cantankerous Beckey. “That’s my rule, and it’s kept me alive all these years.”

With the team back together and after a day of rest, they attempted the Shield. After free-climbing the initial two pitches, Beckey decided to retreat while Franziska and James aided another four pitches before exhaustion, thirst, and a brutal bivy—a cold night spent sitting upright on a small ledge—turned them back the next morning.

In 1997, the trio returned. Beckey, now in his mid-70s, had little interest in climbing the Shield but wanted to go nevertheless, so the Garretts recruited Kris Pietryga, another Salt Lake City climber. Memories of the brutal 13-mile approach spurred the Garretts to hire horse-packer and cowboy Jeff Strock, the only person then authorized by the Tribal Council to guide in the Wilson Creek drainage. Strock, who passed away tragically last year, was from Montana and Blackfoot by birth, but had been adopted into the Eastern Shoshone tribe; he would be the same guide who, more than 20 years later, helped us pack in a Jackery solar-power system and several guitars.

On that 1997 trip, Beckey and Franziska provided ground support while James and Pietryga made efficient work of the lower half. After spending the night atop pitch six anchored by a single bolt and a tenuous gear backup, Pietryga, aiding pitch seven, dislodged a refrigerator-sized boulder that grazed Garrett’s back. “We were completely rattled,” says Garrett. “The fact that we survived was a miracle, and we couldn’t get off the wall quickly enough.”

A third trip, in 1999, included the Garretts, Pietryga, John Chilton, and Ryan Hokanson, with Fred Beckey along again as a technical advisor. Chilton remarked that anyone who returned to the remote wall three times, enduring the brutal hike and blue-collar aid climbing, had “an illness”; the name stuck. After three free and six aid pitches, the team summitted without drama. A triumphant moment, but at 5.10- A2+, a free route it was not.

In 2018, my friends Rowland and Leader, as part of a team led by the Salt Lake City climber Shingo Ohkawa, spent two weeks in the Wilson Creek drainage, eating fresh-caught trout and establishing routes. For their return trip a year later and with an eye on freeing The Illness, Rowland and Leader were keen for fresh recruits. My phone rang. Would I join them? The route was daunting. Hell, even its name was menacing, but with a high-resolution photo of the Shield on my computer and the urge to free an old aid line, I was full in. Garrett told us that the route “should be no problem for a talented, fast-and-light party,” which, unfortunately, we kind of weren’t. Leader is strong, regularly onsighting 5.12, but Rowland and I had only climbed a handful of 5.12s, and none of them alpine. Playing music and singing out of tune, and mixing bad puns with good whiskey, are more our talents.

We needed iron for aiding, static lines for fixing, and two weeks of summer sausages and cheese for our August effort. Our baggage weighed nearly 600 pounds, so we hired Garrett Nimmo, owner of Legacy Outfitters, to pack the load into camp.

“You guys are the only crazy [climbing] SOBs that we bring back in here to climb these rocks,” said Nimmo as one of his two trail dogs, a massive German shepherd with dark eyes, circled us at the trailhead. Affable but all business, Nimmo moved equipment from one saddlebag to another. “Y’all have bear spray?” asked Nimmo, his .45 Long Colt gleaming in the morning sun.

We packed in, set up camp, and headed up to our first objective—Saddle Mountain’s flying buttress. Out of nowhere, a 20-pound rock whooshed right past my face and sledgehammered my foot into the talus. I dropped and grabbed my shoe with both hands, too afraid to take it off; the pain radiated up my leg.

“Miller, what was that sound?” asked Jon Jugenheimer, a smooth alpine climber and late addition to the team. “You OK?”

The shame of getting injured on the approach motivated me to carry on, limping up the snow and scree, to help the team put up Bomb Doors Open (5.9+ X, 1,300 feet). On the traversing first pitch, Jugenheimer dislodged a rock, one of countless loose blocks we encountered on route. The stone looked like it would miss me at the belay, but it took a crazy bounce, struck me on my already-sore, swollen foot, spun me around like a helicopter, and deposited me several feet down-slope.

“Holy shit … I’m alive!” were the first words out of my mouth. Jugenheimer said the same thing moments later when I lurched upright, clearing the lucky stars from my head.

“Goddamnit, Miller, I thought you were dead,” Jugenheimer yelled down as I cinched my climbing shoe over my bruised foot. “Put me on belay,” I said. “I’ll use the climbing shoe as a cast.”

Back at camp that evening, it was time to rehydrate, rest, fish, and abuse ibuprofen. As I soaked my foot in icy creek water, I listened to Rowland’s impromptu cacophony as he strummed a guitar in the key of G.

Jesus was a carpenter, but he never drove a nail

He wanted to play honky-tonk, but he was too scared of hell

He wanted to see neon lights on the Pearly Gates so bright

He wanted to shoot whiskey, get redneck and fight

Mary’s on the dobro and Joseph’s on that bass

Now Jesus is on acid, he’s melt’n off his face

From camp to the head of the cirque was around three miles—a trailless trek over talus and through pants-grabbing scrub, with slick rock-hopping over glassy streamlets and relentless up-and-down ridges. We tackled the one-and-half-hour approach the next day to reach the base of the Shield, guided by Rowland’s bloodhound abilities.

As morning sun warmed the cirque, we stood vexed beneath the climb. Garrett’s route description noted a 150-foot 5.10 splitter to start, but all we could see was an overhanging jumble of gneiss. We rambled around, scouting, and turned up clues: threadbare kneepads, mangled sardine cans, faded tat. Then it dawned on us: The chossy wall before us used to be buried by a snowfield. In the two decades since the route’s FA, global warming had melted the snow, exposing 100 feet of chossy 5.7 below the splitter.

“You think ‘ol Beckey was throwing fucking rad kneebars up there?” Rowland asked, laughing as I strapped on the ratty kneepads.

Leader, who had honed his trad skills through years at the Tennessee Wall, dispatched the initial pitches, and we soon arrived at the fifth ropelength, a flawless 115-foot 5.10 A2 corner, the first of six aid pitches that Garrett had said was a “beautiful dihedral system that quickly narrows down to an unprotectable seam.”

Rowland stepped up. If there is ever a brawl, you want Rowland—thick-boned, rugged, and who grew up where disputes were settled with your fists—on your side, and pitch five looked bare knuckles. Stout as a hickory tree stump, he spent the entire day aiding the pitch on small Peckers, digging out a handful of gear placements and hand-drilling bolts on lead. We then redpointed it at sustained 5.11-, and then, out of time, called it quits.

Our two weeks in the drainage had been a success, with five new routes developed, including lines up Saddle, Thunder Bolt, Lightning Rod, and Front Buttress. But our goal of freeing The Illness remained. “Y’all don’t reckon this route is cursed, do ya?” asked Leader, as we cached gear for a return attempt.

“Nah,” I said, as I counted my heartbeat in my throbbing foot.

A year later, with a world gripped by COVID-19, we once again motored across the country, masks on, figuring that if the 13-mile wilderness buffer up to the Wilson Drainage couldn’t protect us, nothing could.

Our first task was to redpoint pitches one through five and then fix a line on the fifth pitch, the 5.11-. Piggybacking off this rope, we’d then look for a free variation for the sixth pitch, a steep, featureless corner capped by a detached, coffin-sized block.

Leader headed up pitch six. Twenty feet off the belay on the original aid line, he stemmed out splits-wide on granite ripples and gardened a slot for a tipped-out cam.

“Take!” yelled Leader. He sat on the dicey cam and scoped the steep, intermittent seam. “It’s gonna take some more gardening, and they’re gonna be tips locks,” he said. “It looks hard, but I think I can link the seam to another crack.”

Rowland and I were skeptical and told Leader as much, but ignoring my prediction that he might dead-end with no escape back to the belay stance, he said, “Fuck it,” and carried on. After a slopey, unprotected 5.8 traverse, Leader slamed his untaped hands into a tight crack and moved quickly. “Hell yeah, boys!” he shouted down as he started a powerful undercling-hand-jam traverse, smearing his feet on the smooth granite, cranking between jams.

Twenty minutes and 150 feet later, a wide-eyed Leader whooped after freeing pitch six, one of the finest alpine crack pitches any of us had seen. And while we debated the difficulty of the ropelength—5.10+ or 5.11?—it didn’t matter, because it’s pure alpine gold.

Heath took pitch seven (5.10-) and got us to the beginning of the Hateful Eighth while storms brewed all around. Soon, snow and sleet pelted our jackets, and all I could think about was pitch eight’s deadpoint crux to an open-hand “basketball” that was likely now wet. As I climbed off the belay, Nimmo’s words—you crazy SOBs—rattled around in my head.

I crimped hard, a thousand feet up and with a small cam at thigh level, to set up for the deadpoint. “Stay tight! Breathe,” said Rowland. “Your last piece is only a few feet below. Hand-foot match. C’mon!”

I punched up, hit, and stuck the sloper.

Leader took pitch nine, a relentless 150-foot crack of variable sizes that angled from vert to slightly overhanging. This was the “Falling Boulder” pitch that had nearly been Garrett’s demise. “Shit,” Leader muttered as he gardened plants and dirt from the crack, then slumped over as if the air had been sucked from his lungs. “I’m not sure this is gonna go.”

He’d been on the sharp end for over two hours and had gained just 40 feet. His hands were blistered and his face was covered in enough dirt to plant seeds. We’d need Bob Vila and a rototiller to come up and clean this pitch if it were to go free.

“This isn’t pitch nine,” I said to Rowland. “This is fucking pitch-NEIN!”

Leader kept digging, raining dirt and rocks on us, digging a 150-foot-long vertical trench up the wall. When he returned to the belay, he was so spent he had to choke back tears. And, if I’m being honest, I did, too. Leader had gone soul-deep, made an inspired effort, and unlocked the penultimate pitch so we could free it.

Rowland took the final lead with nearly 1,300 feet of air under his feet. Sunlight lit up his face as he breached the summit roofs, at last free from the shadows of the Shield. He grinned through chapped lips. I cleaned the pitch and pulled onto the summit plateau.

“Look,” Rowland said, pointing. “Over there.” A rigid-stem No. 3 Friend stamped [JG] lay right where Garrett had said it would be. This was the cam his team had used for their rap anchor in 1999, and it was still there, undisturbed after 21 years, except with time the cam springs had lost their tension and the unit had fallen out of the crack.

We basked on the summit in the warm afternoon sun, and I wondered whether being average climbers is a curse or a gift. I settled on it being a gift because we don’t have to concern ourselves with performing well—if we were superstars we’d be in the spotlight, and expected to always climb hard. I also wondered what Beckey would have thought about The Illness going free. He climbed for a lifetime, but never at the highest level. He just got stuff done.

I got my answer later when I asked Garrett that very thing.

“I don’t think it would have even entered his mind,” said Garrett. “To him, the FA would have been done, and he would have been busy looking for the next classic alpine route.”

I guess we hadn’t cured The Illness, after all.

Bryan Miller operates Fixed Line Media, a climbing-content company in Charlotte, North Carolina.