Learn This: Simple Leader Fall Self-Rescue

"None"

This article originally appeared in the August 2015 issue of our print edition.

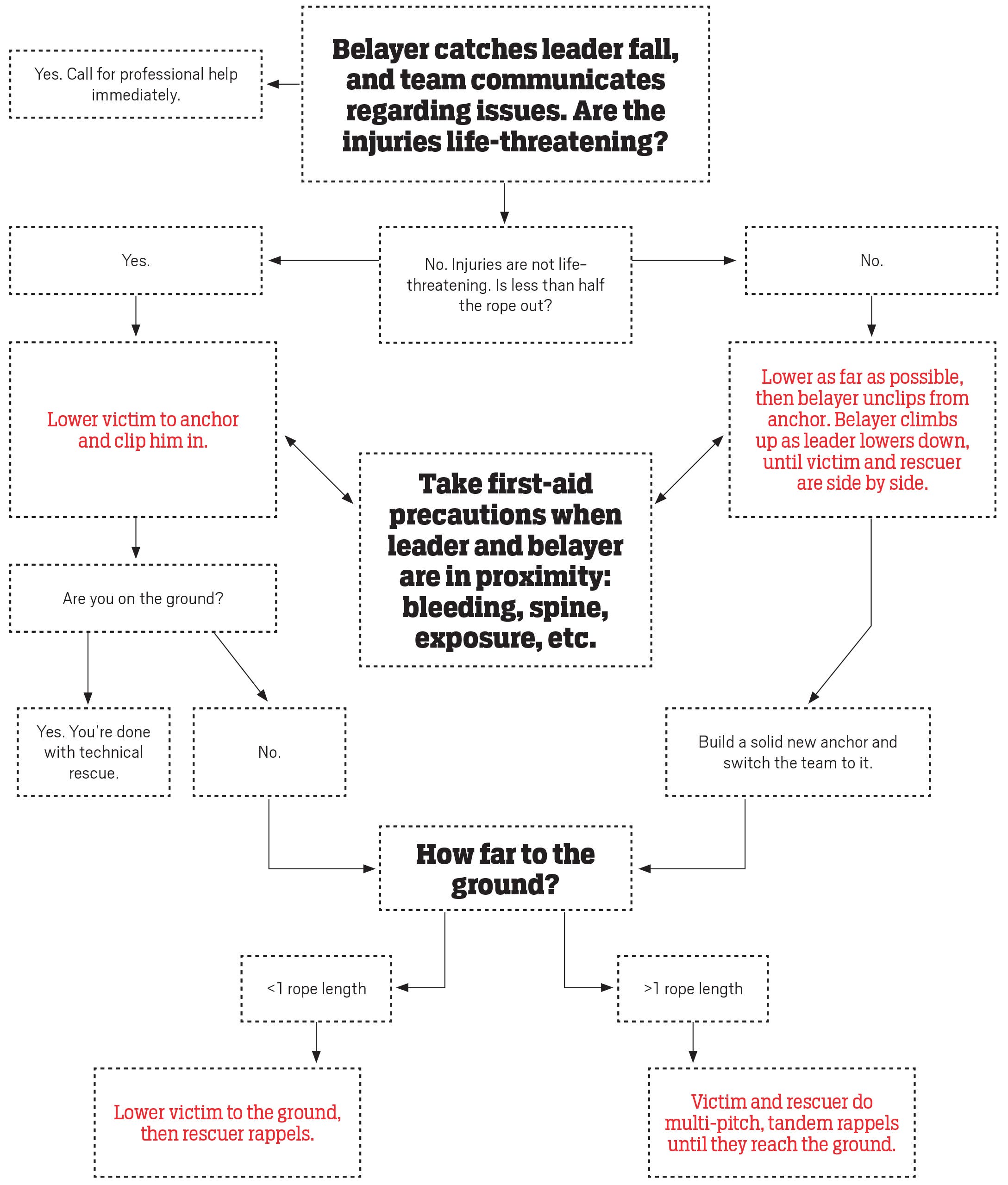

If you’re trying hard and pushing yourself, lead falls are a common, sometimes fun, and always spicy part of climbing, but occasionally a fall can injure the leader to the point where he can’t climb up or rappel down on his own. In this situation, you need a simple, fast solution that safely gets both climbers to the ground instead of an overly complicated approach that bogs you down with load transfer and hauling systems. Despite the dozens of variables that exist with any route, there’s a simple process you can follow that involves virtually no special skills. Whether you are well-versed in rescue techniques or brand new to them, the following actionable advice will help you determine the best method of getting off the wall and safely to the ground.

Assess the injury

The first step is to assess the injury: Is it life-threatening? Is the climber responsive? Sometimes the injury sustained in a climbing fall is so severe that the climber is unresponsive and helpless. A case like this requires a well-practiced repertoire of specialized rescue skills, and unfortunately, even then, the chances of a climbing team successfully getting the victim to help are very low. If the injuries are life-threatening (think: head, back, neck), you need to call for a professional rescue immediately. The good news is that the vast majority of injuries from lead falls are not life-threatening (think: leg, arm, foot), and the victim can assist with his own evacuation. With a cooperative victim and basic climbing skills, smooth self-rescue is entirely possible. Administer first aid as needed during the retreat process.

Assumptions

There are a few requirements in order for these techniques to be successful: a team of two climbers using one single-rated climbing rope; the protection that held the fall, backed up by at least one more piece of gear below; a roughly vertical route; a leader who is injured, with decreased mobility, but is conscious and cooperative; the belayer tied into the other end of the rope; the team has a substantial rack and will leave gear behind; the rescuer is skilled with anchor building and multi-pitch rappelling. The only special skill necessary is tandem rappelling, which is straightforward and outlined below. Keep in mind that retreating will take almost as long as it took to climb to where the injury occurred.

A few notes…

You’ll be relying on the topmost piece of protection. Note that this protection has already held a significant fall, and it should be backed up by pieces placed below. With the injured climber hanging on the climbing rope, the top piece is already exposed to roughly twice the force of that climber’s weight because the weight is opposed by a force equal to that on the belayer’s side, essentially doubling it. Forge on with lowering and rappelling, and trust the fact that protection basically never slides out of place under static load.

The initial goal for any situation is to get the climber and belayer into close proximity for first-aid assessment. Lowering an injured climber even a short distance is difficult for the victim and exposes him to potential secondary injuries. This is a judgment call. Having the rescuer and victim side by side allows for rapid initial assessment of life threats. Delaying that process in the interest of comfort or preventing additional injury must be considered very carefully and might require additional special rescue skills (belay escape, rope ascension, etc.).

A final thing to consider is the mobility of the injured climber on the ground. Ironically, someone with a lower-body injury is much more portable on steep terrain than walking or scrambling. Call for help from the cliff so there will be someone on the ground by the time you and your partner get there.

Tandem Rappelling

1. The rescuer should rig herself to rappel using an extended device with an auto-block backup.

2. Clip the locker from the victim’s personal tether onto the device and through the rope (stacked below the rescuer’s rappel biner, two people on the same device); this extra carabiner in the system adds friction.

3.Adjust lengths so that the rescuer and victim hang hip to hip. Or, if the victim is lighter, make the tether and extension a little longer so the victim can swing onto the rescuer’s back.

4.Victim and rescuer will need to work together to lower over edges, navigate obstacles, and make decisions as they move down.

Jediah Porter (jediahporter.com) is an IFMGA-certified Ski and Mountain Guide based on the road. He regularly tests gear and writes for Climbing magazine.