Tech Tip - Alpine - Shelter For The Storm

"Tech Tip - Alpine - Shelter For The Storm"

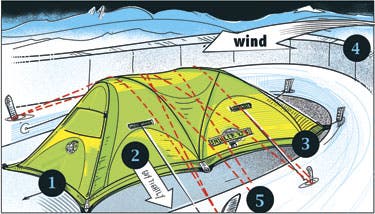

Pitching the perfect tent in the high mountains

When a storm hits, most expedition climbers play cards, pick lint off of their boot liners, or fantasize about sipping Mai Thais. A little “tent pitching” and a flask of grandpa’s cough syrup easily bide the downtime for most, but when Mother Nature blows nuclear-strength wind and weather directly onto you, you don’t want to be that sorry sap chasing after a torn-up tent. Here are a few pointers to prepare your “perfect” shelter for the storm.Set up or Shut upA sloppy set-up means more work in the long run — get it right the first time. Your tent’s main entrance should face downwind, with the long axis aligned parallel to the wind. Do as much prep work on the ground as possible, attaching the tent to at least one anchor point on the windward side and sliding all poles through their sleeves (or clips), so they can easily insert into their respective gussets the moment you raise the tent.The RootsOnce you’ve placed the fly, secure the back vestibule with a solid anchor. (This windward-side anchor will take the brunt of the blow, so make sure it’s bomber, with a secure picket, deeply buried deadman, or a pile of rocks heavy enough to hold strong when you’re tugging on the guy lines.) Next, anchor the tent’s front vestibule (the main entrance), ensuring that the tent’s long axis is fully stretched and taut; then work your way around the tent, guying out the fly. A properly secured tent body and fly will diminish excessive flapping, which stresses the material and creates obnoxious, sleep-interrupting noise.SkirtsIf you spend lots of time in nasty conditions, add a valance: a wide flap of nylon running around the fly’s bottom edge (buried under snow). Widely used outside the United States, the valance acts like a powder skirt of sorts — it minimizes snow blowing up underneath, helps anchor the tent, and reduces fabric flappage. In the States, your best bet is to hit the fabric store, and then sweet-talk your grandma (or local tailor) into sewing the valance into place. In Antarctica and similar locales, valances are the norm.BulletproofSnow walls provide additional wind blocking. Build your snow walls as tall as the tent and distant enough (3 or 4 feet) to provide ample room for such tasks as moving guy lines and shoveling snow. When the wind is especially strong, build two concentric rings, or make a single wall two blocks thick. This will further mitigate direct wind and drifting, and also mute the beastly howl.Calling All ReinforcementsIn punishing winds, reinforce your position by lashing a climbing rope back and forth over the tent. If you have a second set of tent poles, insert them alongside the original poles (i.e., parallel), to augment the tent structure. And for internal fortification, place backpacks, boots, and bodies against the most wind-beaten wall.HousekeepingA snow-cloaked fly can collapse the tent. One indication of snow build-up is a dampening of noise (i.e., less howl) and a loss of ambient light. If you’ve gotten to that point, you’re behind the ball — it’s maintenance time! Use either a gloved hand for snow removal or, if you must, a shovel, taking special care not to shear a guy line or cut the tent itself.Back up“Be, be, be prepared” — it’s the motto of the Boy Scouts, and it’s a good one. Unless you prefer freezing to death, you’ll need to act quickly if the tent has collapsed, thereby snapping your poles and tearing apart your shelter. Can you dig in? Where’s the best place to dig a snow cave? (To prepare for this eventuality, you should scope alternative bivy sites and suitable escape routes during fair weather.) Instead of sleeping with a teddy bear, rest with your shovel, and keep your headlamp and warm layers close at hand. If it’s terminally nuking, sleep with a knife, a measure of last resort you can use to cut through the tent.Hearts and whiskey are Molly Loomis’ preferred ways to pass a stormy day.