Derided By Many, Speed Climbing Could Still Decide Who Gets Olympic Gold

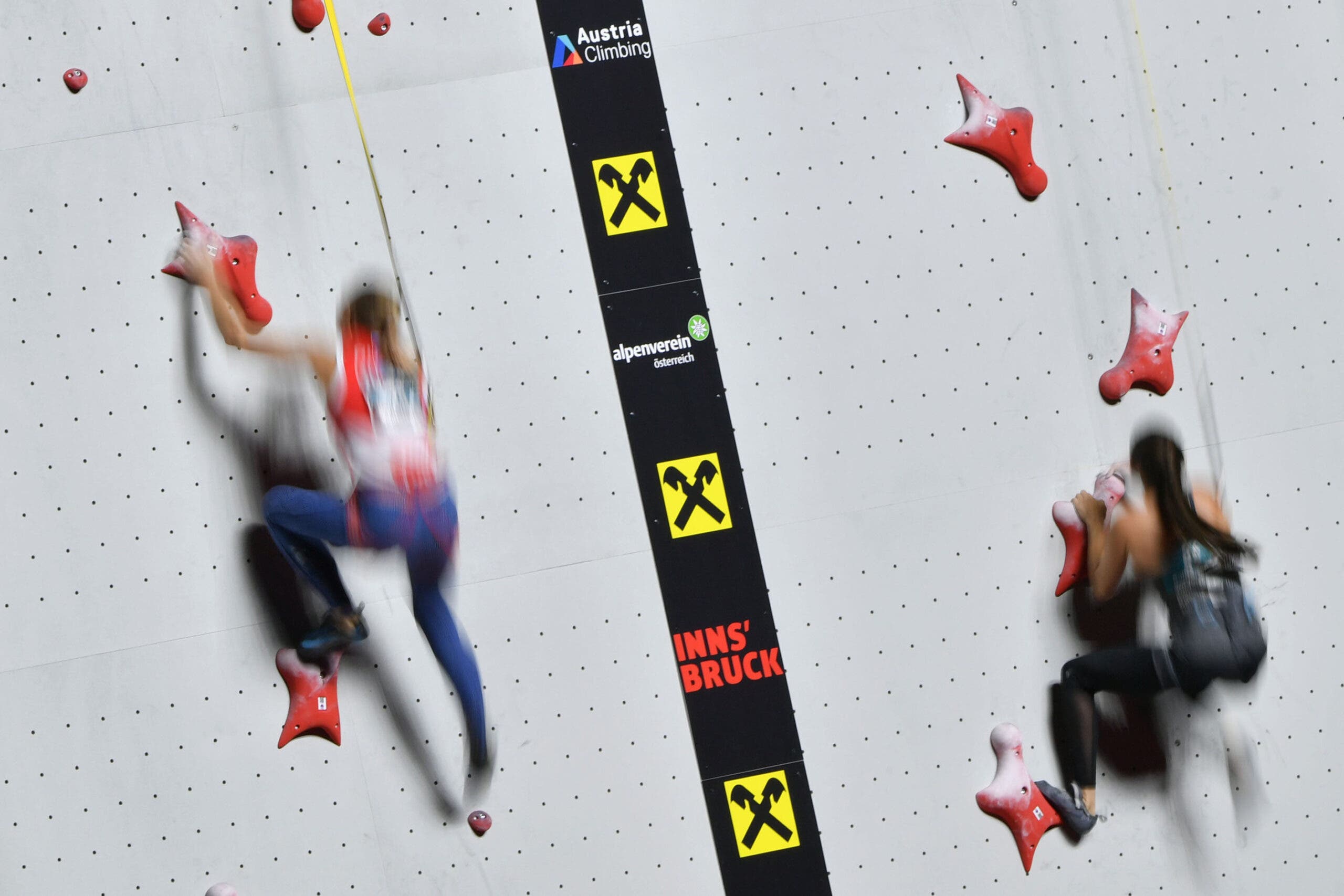

Bassa Mawem of France is a speed specialist. (Photo: BARBARA GINDL/AFP via Getty Images)

This article is part of our ongoing coverage of the 2020 Olympic Games. For more news as it happens, and for unlimited online access plus a print subscription to Climbing, join us with an Outside+ membership.

It’s safe to say that prior to the announcement of climbing’s Olympic inclusion, many boulderers and lead climbers had little interest in speed climbing. Even once the Olympics’ unique Combined format (in which speed climbing, bouldering, and lead climbing are to be contested sequentially) was unveiled, bouldering and lead specialists were…well, vocally unenthusiastic, to put it nicely. I remember interviewing Team USA’s Nathaniel Coleman a couple of years ago and he told me overtly, “Speed climbing is something I don’t like.” A lot of the qualified Olympians shared Coleman’s initial sentiment. Yet, at this point—with the climbing at the Olympics just days away—most competitors have warmed up to speed climbing. Some have even grown fond of it. And the more the speed discipline gets analyzed in the context of the Olympics’ Combined format, the more it seems like it could end up being the determining factor—or at least a wild card—in deciding who wins the gold medal. Here’s how…

Also Read: Spectators Think Climbers Are Failures

Out of the Comfort Zone

There are seven climbers on the Olympics’ roster who are “speed specialists”: Italy’s Ludovico Fossali, France’s Bassa Mawem, and Kazakhstan’s Rishat Khaibullin in the men’s division; China’s YiLing Song, Russia’s Iuliia Kaplina, Poland’s Aleksandra Miroslaw, and France’s Anouck Jaubert in the women’s division. Beyond them are 33 qualified Olympians who have tried their darndest to get really good at speed climbing over the past few years. And, to everyone’s credit, a number of them have gotten really good—Japan’s Miho Nonaka made the podium at a Speed World Cup; Slovenia’s Janja Garnbret went sub-8-seconds in a speed run; Team USA’s Kyra Condie seemed to improve her speed time each time she entered a race.

But there’s a big difference between getting really good and becoming elite. Despite all the improvements by the non-speeders, the top spots in the Speed portion of the Olympics are still likely to go to speed specialists. That means the middle of the results will likely be an unprecedented mix of outcomes. Some non-Speed specialists will likely have the speed runs of their lives, while others will likely make spirit-crushing mistakes. This is the variation that comes with having a lot of competitors participating in a discipline that is not their area of mastery. And, given the multiplied scoring of the Olympics Combined format, a low rank after the speed portion could leave some competitors in too big of a hole heading into the other disciplines, specialists or not.

No Room for Errors

One of the factors that makes the Speed portion of the Combined format unique from the other disciplines is how unforgiving it is, in regards to mistakes. A good Speed run in the men’s division typically lasts between 5 and 6 seconds; a good run in the women’s division is in the low-7-second range. In other words, the climbs are supremely fast. As such, the slightest slip or blunder during a run could be catastrophic in the scores…a competitor’s shoulders leaned ever-so-slightly to one side, toes did not land on the precise spot on a foothold, hand missed the buzzer at the end of a run. (Check out Indonesia’s Veddriq Leonardo setting the men’s World Record to see how much precision is involved in every single movement.)

On top of that, a competitor’s Speed run could be over before it even begins, as a false start automatically results in losing a heat.

Also Read: Team USA Is Having Its Best Year Ever

Consider how different this is from the Boulder portion, in which a slight slip or blunder isn’t nearly as costly. Competitors are free to try a boulder again—as many times as possible, in fact, within the allotted time. The stakes are raised a bit in the Lead portion, as one slip could certainly result in a fall and the end of a competitor’s attempt. But extremely low slips on a lead wall are fairly uncommon, and falls on a lead wall’s starting holds are rare in elite competition—yet false starts and low falls are seen in nearly every Speed heat and will almost certainly happen at the Olympics.

Again, the aspect that makes a slip, fall, or false start in the Speed portion of the Combined discipline so weighty is the multiplied scoring. As a hypothetical, let’s say that a competitor gets 1st place in Speed, 2nd place in Boulder, and 2nd place in Lead. That competitor’s final multiplied score would be (1x2x2): 4. Contrast that with the score of a competitor who makes a couple of slips and a false start in Speed to finish the discipline in, say, 15th place…and 2nd place in Boulder, and 2nd place in Lead. That competitor’s final multiplied score would be much worse, (15x2x2): 60. That’s a difference of 56 points in the final scores, all because of a couple of slips and a false start. Brutal.

Key Matchups

There are a number of key pairings to keep an eye on at the Olympics, particularly as they pertain to Speed. First, Japan’s Tomoa Narasaki and the Czech Republic’s Adam Ondra are two of the favorites to win the gold medal in the men’s division, but they each have different areas of specialty. Narasaki is a boulderer who has excelled at Speed. Ondra, in contrast, is traditionally a boulderer and lead climber who has historically struggled in Speed. If Speed was not part of the Olympics’ format, Ondra would certainly be the universal favorite. However, given Narasaki’s proficiency on a Speed wall, one has to see them as more or less having the same odds for Olympic gold. Those odds swing significantly in favor of whomever has the better Speed portion. In the women’s division, I’m particularly curious to see which speed specialist finishes highest through the bracket-style format: Kaplina, Song, Miroslaw, or Jaubert. Beyond them, there are a number of competitors who have clocked speed runs around the 9-second mark: Japan’s Akiyo Noguchi, Team USA’s Brooke Raboutou, Great Britain’s Shauna Coxsey, to name a few. I can’t help but wonder which one of them will perform best in Speed. I’d also like to see Team USA’s Kyra Condie line up beside Slovenia’s Janja Garnbret for a race. As mentioned previously, Garnbret has gone sub-8-seconds, and Condie posted a blazing personal best time of 8.05 seconds at USA Climbing’s National Team Trials a few months ago. Something tells me this would be a heckuva race, neck-and-neck the whole way, and it could set the tone for either competitor as they chase gold in the other disciplines.