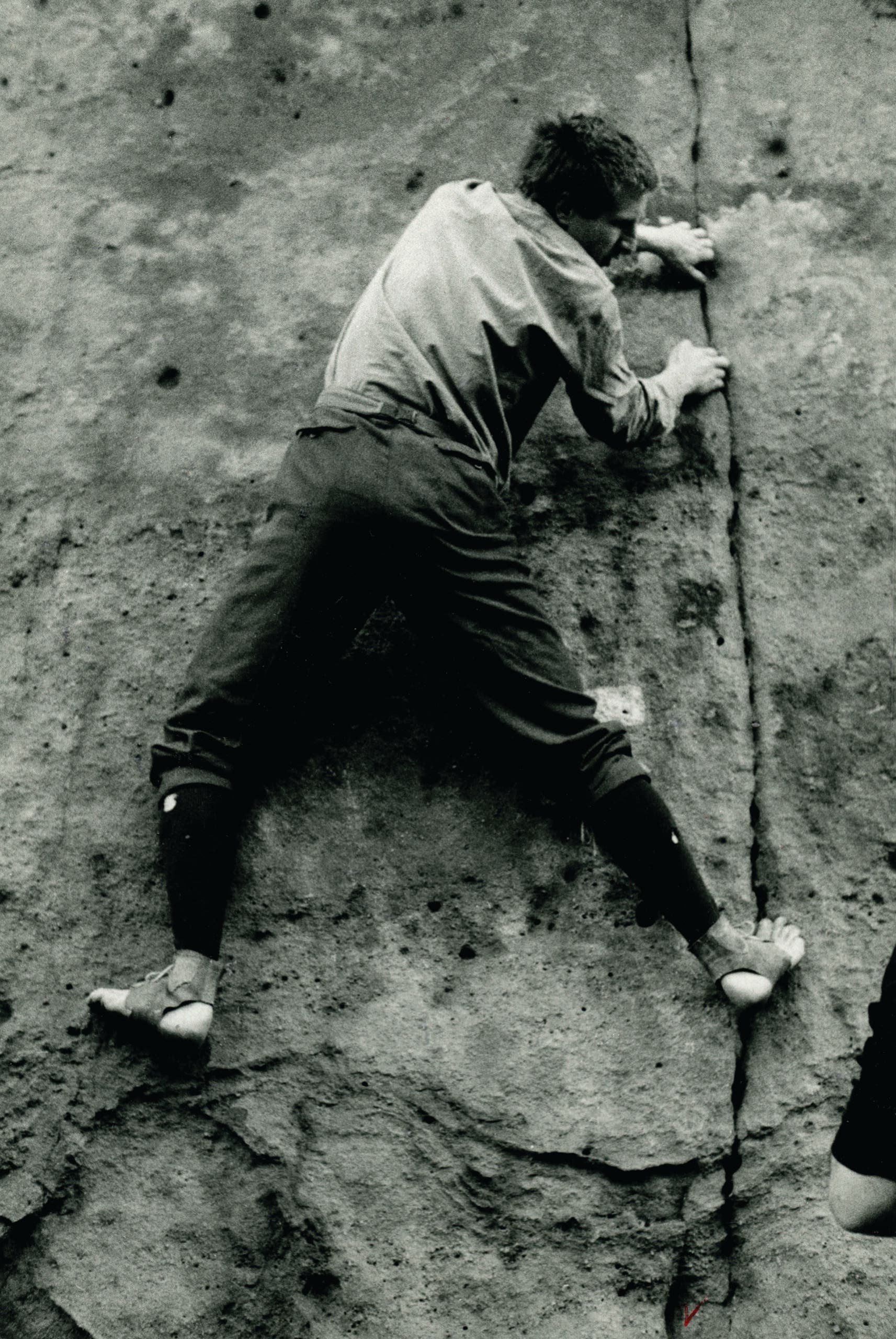

Steve Roper Meets His Match On The Fearsome Walls Of Dresden

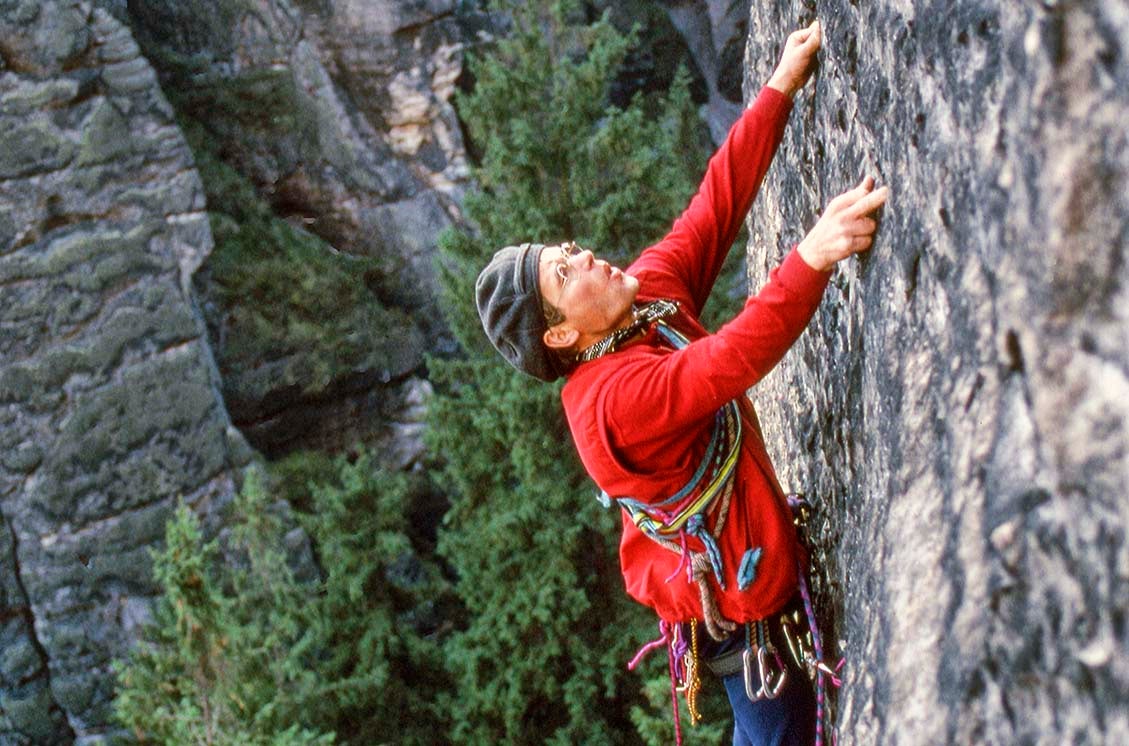

Elbsandstein master of sport Bernd Arnold, on a first ascent, onsight, no chalk, with jammed knots for pro. Arnold was prolific in the Dresden area, putting up many of its most difficult routes in the 1970s. (Photo: Duane Raleigh)

This feature article was published in the 2017 50th anniversary edition of Ascent. It is published here free as a thank you for supporting us in 2022.

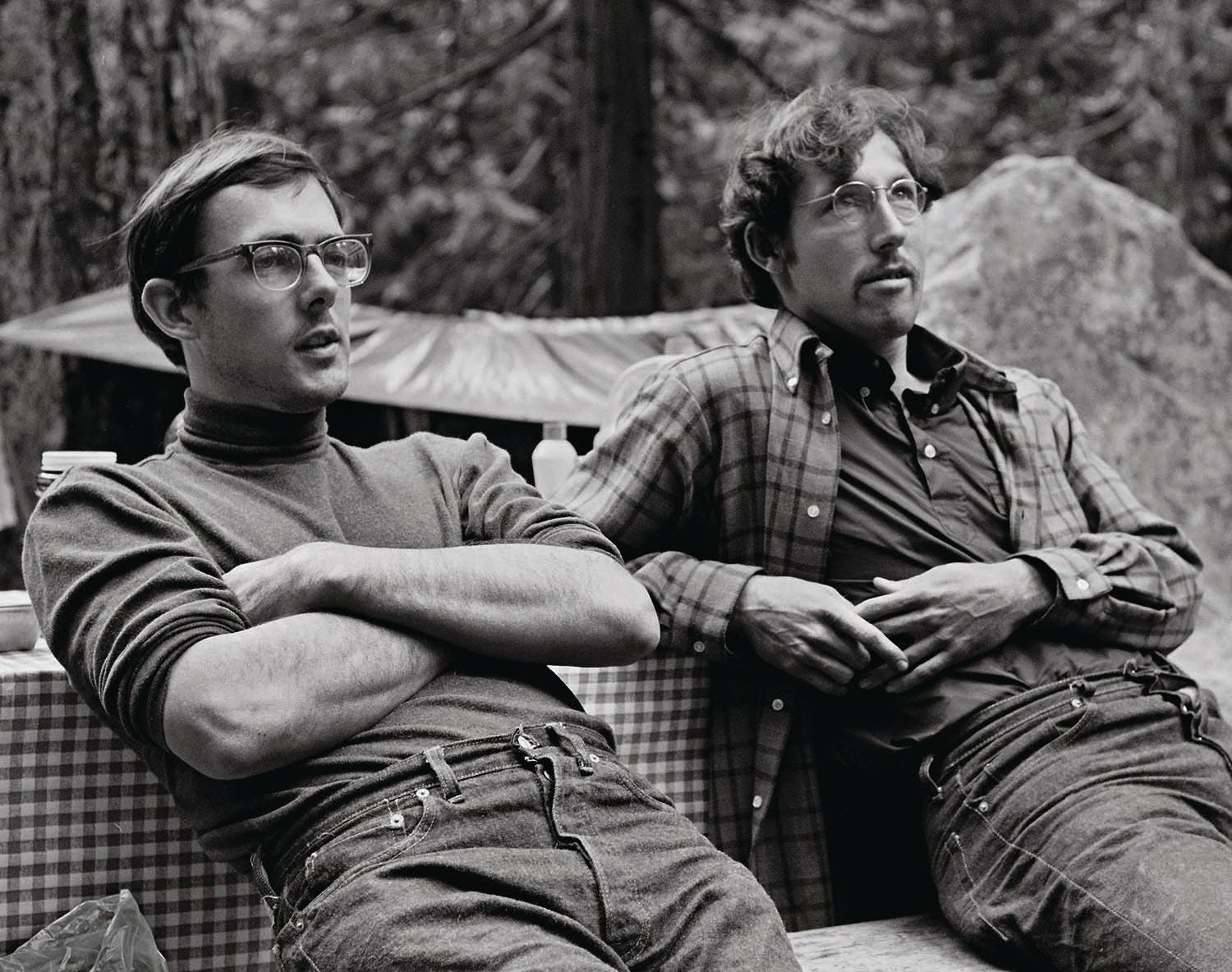

EDITOR’S NOTE: Steve Roper was an icon in Yosemite Valley during what we now think of as the “Golden Era,” the 1960s. His partners were storied characters such as Chuck Pratt, Layton Kor and Royal Robbins, and his routes included, in an era when big walls were great unknowns, the third ascents of the Nose and the Salathé on El Capitan and the first single-day ascent of the Northwest Face of Half Dome.

Erudite and insightful, Roper was Yosemite’s great historian as well, producing one of the best climbing guides ever written and later the comprehensive chronicle Camp 4: Recollections of a Yosemite Rockclimber. In “Dresden,” Roper turned his verbal precision and humorous eye to a trip not just outside the Valley but outside anything then known to our community.

In 1969 he received an invitation from the great climber Fritz Wiessner to visit the sandstone pinnacles of Dresden with him. Wiessner had long said that the greatest climbers in the world were climbing there in isolation, with neither pitons nor nuts. Roper was one of the first American climbers to peer behind the Iron Curtain and see if the wild tales emanating from therein could possibly be true.

In another seminal event, Roper and Allen Steck served as cofounders of Ascent, first published in 1967. They put it together amid many late nights and with much merriment and wine.

I had slowed down, no doubt about it. Climbing less than once a month, and nothing very demanding at that, had made my muscles flaccid, my brain porous. Other (read: safer) interests, coupled with far too much wine, had interfered with a solemn promise made to myself 15 years previously: I love climbing, it is the best of all possible activities, and I will climb, climb, climb for the rest of my natural life. So I had to smile a wry smile when I was asked along on a climbing trip to East Germany by a man who for over 50 years had actually obeyed this credo. Fritz Wiessner, before I was even born, had climbed in Asia (reaching 27,500 feet on K2), made numerous short forays into the Alps, and put up about 50 new routes in North America, including on Waddington and Devil’s Tower. But of all the places Fritz had been, there was one that he loved above all others: Saxon Switzerland, a hundred-square-mile area along the banks of the Elbe River near Dresden. He was born in this incredibly lovely place in 1900 and by the age of 18 was already leading some of the hardest climbs of the region.

The name Saxon Switzerland is misleading. It does, in fact, lie in the state of Saxony, but whoever bestowed the rest of the name must never have seen Switzerland, for there is no permanent snow, and the highest point fails to attain even 2,000 feet. The German name for the area, Elbsandsteingebirge, seemed too hard to say, so I began to refer to the region simply as Dresden. It is hilly country, and the river makes very lazy turns through forests and fields. Occasionally a ridge of sandstone has been eroded by the Elbe, and it is here that the climber pauses. The rock is a dense and non-crumbly variety of sandstone, much more akin to that of El Dorado Canyon in Colorado than to the towers of the American Southwest. About 5,000 routes have been established on the 900-odd pinnacles. Though the climbs nowhere exceed 80 meters in length, there is a great exposure, and, as I was to find out shortly, great continuity. Steep and continuous. Intimidating. Scary.

Over the years I had known him, Fritz had intimated that the Dresden climbers were equal to the best free climbers in the world. A startling Dresden climbing movie he showed at the annual American Alpine Club dinner in 1967 left the audience wiping palms on pants and me feeling that Fritz might well be right. By this time I was literally off big-wall climbing, preferring short free climbs in new areas. So to me the movie offered a fascinating glimpse into what easily could become my personal mode of climbing: head for a strange area, get into shape on the old classics, swill wine and bullshit with the locals, loaf, then build up to some of the new classics. Then split. No pressures, no aid climbing, no bivouacs. An easy way to climb, you say, but it would be my way.

In the winter of 1968–1969 I received a letter from old Fritz: Come with me to Dresden in May. I met him in Interlaken; we gravitated south, climbing in small areas, getting into shape. Then, halfway up a 200-meter wall in the South of France, Fritz began striking his chest, cursing in his gentlemanly style, proclaiming “indigestion.” Unfortunately, it was a bit more serious than that: his heart was beginning to crap out. A few months of rest and Fritz was completely recovered, but in the meantime our 1969 expedition to Saxony had met its end on the Riviera.

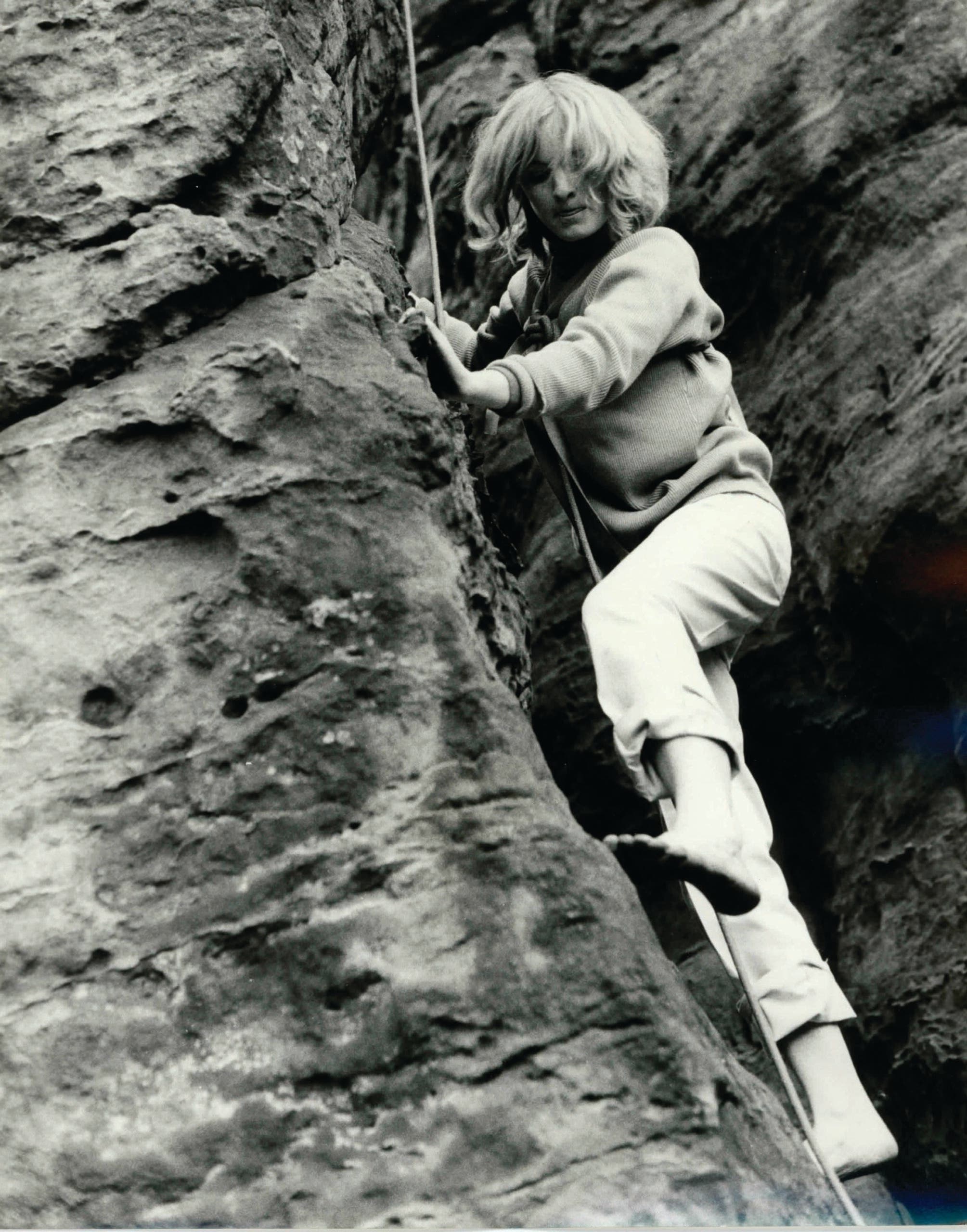

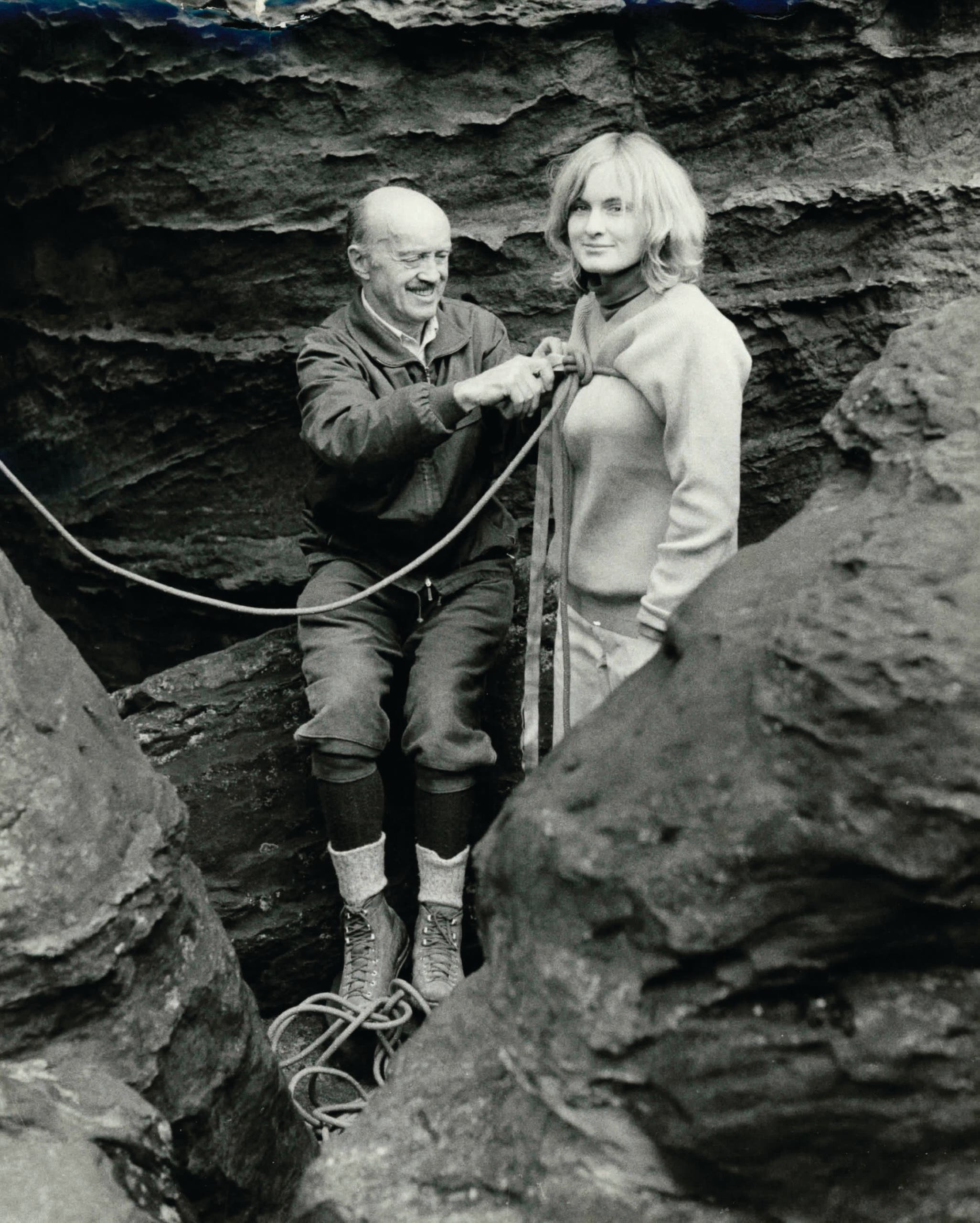

My next chance came in the spring of 1973; Fritz was 73; I felt like 53 (a winter of nose-to-the-grindstone hedonism had taken its toll); it seemed an inauspicious time and a team of which no one could have said—as I did in my early Valley days, in mock seriousness—“This is the finest team ever assembled.” A third member was Fritz’s daughter Polly, who, during those frequent interludes when Fritz would rattle along in German to his old and new cronies, became a valued friend. Already used to climbing barefooted, Polly would fit into the Dresden climbing scene with ease.

This feature article was published in the 2017 50th anniversary edition of Ascent. It is published here free as a thank you for supporting us in 2021. Ascent, founded in 1967 by Yosemite pioneers Allen Steck and Steve Roper, is published once a year and is included with an Outside+ or Climbing membership. Please join us with a membership and receive the spring 2022 Ascent edition.

Paranoia is not my usual state, but I had begun to have a nagging fear that on this trip I was to be exhibited as the Yosemite Fanatic, fresh from wild cracks and thousand-meter walls. So as we drove down the deserted Autobahn toward our destiny, I began my final harangue: Fritz, old chap, I’m in foul shape, you know, haven’t even been in the Valley for a year, and I do not wish to be portrayed as the American Star, I do not want to get hurt, not badly, anyway, a sprained ankle would be quite nice, we could motor over to Prague and sightsee, you realize, Fritz, that I’ve never been in this part of the world, and I’d sure hate to miss Prague, indeed, why don’t we spend a few days over there when the weather goes bad, as I hope … ah, I mean as it’s sure to do sometime and there’s no point in sticking around in a drizzle, right, Fritz, and by the way there’s also no point in jumping right into the tiger climbs; we’ll be here 16 days, after all, and I don’t really want to get hurt this far from home, christ, I don’t even speak the language, imagine a hospital stay, jesus, they’re asking me for my identity card and here I am lying here with a … Then Fritz breaks in, saying, don’t worry, Steve, we can climb in the rain, it’s done all the time, not the sevens of course, but the sixes, he assures me, will be in fine shape. Then I recover, seeking my manhood, saying, boy it’s sure nice to be headed for a new climbing area, what are we doing tomorrow?

Tomorrow. Overcast, visibility a mile in rain and fog. I am introduced to two climbers, old types in their 30s. Günther and Friedrich give crushing handshakes while their eyes seek the secrets of Yosemite. But they’re not mine to give, fellows, not anymore. I’m just here because … because God, Roper, get a grip, quit whining. Calm your brain.

A few easy climbs lull me into rainy-day torpor. Then, at the base of a giant overhanging pinnacle, I see a confab. I know no German, but I get the idea pretty quick. I follow their looks upward, I watch Fritz making some sort of apology (I’m not paranoid, I reiterate!), and I see an agreement reached. Perhaps this agreement has doomed me, but I have no choice. So must an unwilling bride feel as the dowry is discussed. With downcast eyes I follow Günther to the rock. Then my savior, Fritz, speaks: At first you would like to follow, yes? To get used to the rock, which is much different than in your Valley.

And so the first days go by, and I get into a bit of shape. I love the rock, even though Fritz thinks I prefer Valley granite. Actually I think I climb better on almost all other kinds, and the Dresden rock is a super-rock, solid, with edges, offset cracks, flakes; beautiful. Often just Fritz, Polly and I climb together. It is often pure joy to watch the septuagenarian climb, a half-century of technique behind him, every move precise and thoughtful, but then I feel sad when I watch once-powerful arms quiver with the strain of a pull-up. But, god, if I could climb like that in 2014 …

The grading system used in the area is just about as inconsistent, illogical and provincial as most other systems. Roman numerals from I to VII are used to indicate free-climbing difficulty. At some point they ran into that problem faced in so many areas: when harder climbs are done, what do you call them? Rather than go to VIII, they have subdivided the VII category into a, b and c. Yet, it seemed to me, each letter represented a palpable step upwards: VIIa is to VIIb as V is to VI. They can no more jump up to an VIII and a IX than the NCCS can head toward a 12. Only the Australians seem to have solved this particular problem: they have an open-ended system with no magic top number. Thus, when a climb recognized as harder than their present hardest, a 21, is done, it becomes, without controversy, a 22.

Late in the first week Fritz tells me that the breaking-in period is over; tomorrow we meet Herbert Richter, an Ex-Master of Sport, and now a physicist. He will climb with us for a week. With trepidation I shake hands with Herbert. He looks amenable, is a bit of a clown, and speaks English to a degree. Later, Polly teaches him the phrase: “so-and-so is lewd, crude and socially unacceptable.” He loves this, and soon I hear him muttering, in the midst of a 5.10 move, “this rock is lewd, crude … ” A fine chap. I liked him immediately. But, he was an Ex-Master of Sport, and he was serious as hell about climbing. To be a Master of Sport (a phrase I like to roll around on my tongue much like Herbert with his “lewd, crude … ” one must climb, per year, a set number of fearsome death routes. Apparently Herbert hadn’t done enough of these, or had had a falling out with the people in charge of Sports, for he was an Ex.

Unlike the U.S. State Department, the East German regime recognizes that their hot climbers are an asset and they send them to various places within the Eastern Bloc for climbing competitions and expeditions. But unlike their Polish, Czech or Russian counterparts, they are never allowed to cross into Western Europe, and I sensed that Herbert must mourn this, that he must often have thought: My whole climbing life will be spent on these rocks, no wonder I am an expert here, but what of the Alps? I dream of the Eigerwand, the great Chamonix aiguilles; perhaps I would fail there, but how do I know? I read what I can, but we get few books here, and I have a family and cannot flee. And perhaps it is not that good outside? Herbert, I would gladly have told you of the rotten, insane and corrupt form of government our democracy provides us with. But I’m not sure I would have liked to tell you this: We’re free, man, we can travel thousands of miles with no controls whatsoever; we can climb anyplace on Earth.

And so the Ex-Master and I trotted over to one of the new classics, the Höllenhund (the Hound of Hell), an 80-meter wall averaging about 90 degrees. Sieben C (VIIc), he told me. 1967. A fine route. It was a different kind of rock from what I had already become accustomed to: it was full of small holes, tiny jugs, stalactites. It didn’t look too bad. Polly and Fritz stationed themselves in relaxed positions to watch the debacle. Herbert took off, climbing flawlessly, reminding me instantly of Robbins, not particularly graceful, but super-cool, super-competent, almost arrogant in his control. And very safe. He threaded runners through holes so tiny that a 7mm rope would not fit doubled. He would hover above me, clinging to pinch holds, untie a length of rope, thread it through a hole, then retie and jerk. Yeah, it didn’t look too bad. I think one reason I hate to climb with guys like Robbins and Herbert is that they make it look so easy that I relax and lose the fine psychological edge which I have built up to on the approach march.

I think I could have done better if I hadn’t had to stop and untie 12 jerked-taut runners. My arms ballooned, and I dwelled overly long on Robin Smith’s phrase, “Then my fingers turned to butter.” Mine went buttery just as I lunged for his hanging belay. Jesus, I told him, good lead, dad, what’s it like above? The same, eh? Well, Herbert, be a good fellow and lead on, I’m wiped out, you know, jet lag and bad food, no, not bad, Herbert, just different, actually, you Germans sure know how to cook, yes siree, those giant liver dumplings are out of sight, as we say, yes sir. And so Herbert danced on, savoring his role, assuaging my inferiority complex with kind words. God, I thought, we have another week of this and my arms will be horrible tomorrow; how can I talk Fritz into Prague?

Luckily there were a few rainy days, and Fritz took us around Dresden and reminisced: Here was where our school was, here there was a marvelous square with a fine view toward the museum. It was all “was,” for on my fourth birthday, as I was mindlessly devouring a cake, the Allies were mindlessly bombing this most beautiful of cities. The war had only 80 days to run; Dresden was an acknowledged non-military target, a cultural landmark. Nevertheless, a hundred thousand people and a city among cities no longer exist. So it goes. The damage has, of course, been swept away, but the reconstructed buildings are cheap and efficient; aesthetics have received a low priority under the present regime.

Fritz had insisted that I buy a pair of EB’s for this trip, and I had rebelled, of course, for one doesn’t like to be ordered about, especially by a father-figure, and anyway I had a beautiful pair of RR’s, perfect fit, no complaints, and here I had to buy a pair of weird expensive shoes. I bought them as instructed, but I hated the idea. From the first day, however, the EB’s were magical; it was a case of the shoe fitting the place, or however the cliché goes. I could put my foot anywhere, and it would stick. So imagine my anxiety at the base of the Höllenhund when I saw Herbert strip his wretched hiking boots and strap on bizarre gauntlets of leather which covered only half his foot, leaving vulnerable the (to me) crucial part, the toes. Christ, I can’t even walk barefoot along a street, and here this dude, strapping on a device best left to a porno flick, was preparing for 5.10. But East Germans have prehensile toes, it seems, and I would slack off belaying to watch entranced as those toes would seek sensuously for a hold, and then I would glance down at my beautifully encumbered feet and curse, knowing that once again I’d been had. And sure enough, the magical EB’s can’t compare with the great toe when it comes down to a one-inch-by-one-inch hole in the rock.

One day I was informed that a new climber would join us. Herbert, with just the barest trace of envy, said, “It is our Star, Berndt Arnold.”

Your Übermensch? I asked, and Herbert had to laugh. Not quite the exact translation, perhaps, but we laughed a lot, and it became a trip phrase. When you’re among friends the language barrier is not what it’s made out to be. We met Arnold at dawn at the printing shop he runs, an inconspicuous place in a village 20 miles out of Dresden; and they told me of the Star leaving work at five and trotting a few miles to the rocks and bouldering until he was exhausted, and then the weekend would arrive and with it his comrades from the city, and he would shine and shine and was surely fated for the National Team. I must say that he was an intense climber, a Master, a true Übermensch. I watched from below while he and Herbert climbed a fearsome wall, a Master climb. I had begged off, so Fritz and I lay down in classically comfortable postures and watched the drama above, Fritz thinking how a few years ago he would have been first on the rope and poor humbled Roper thinking how glad he had made his feeble mark and was no longer compelled to get up there and prove his worth and, more important, risk his balls. But I loved watching the climbers move, and it showed me at last what Fritz had been implying all along: these fellows around Dresden are among the best free climbers on the planet.

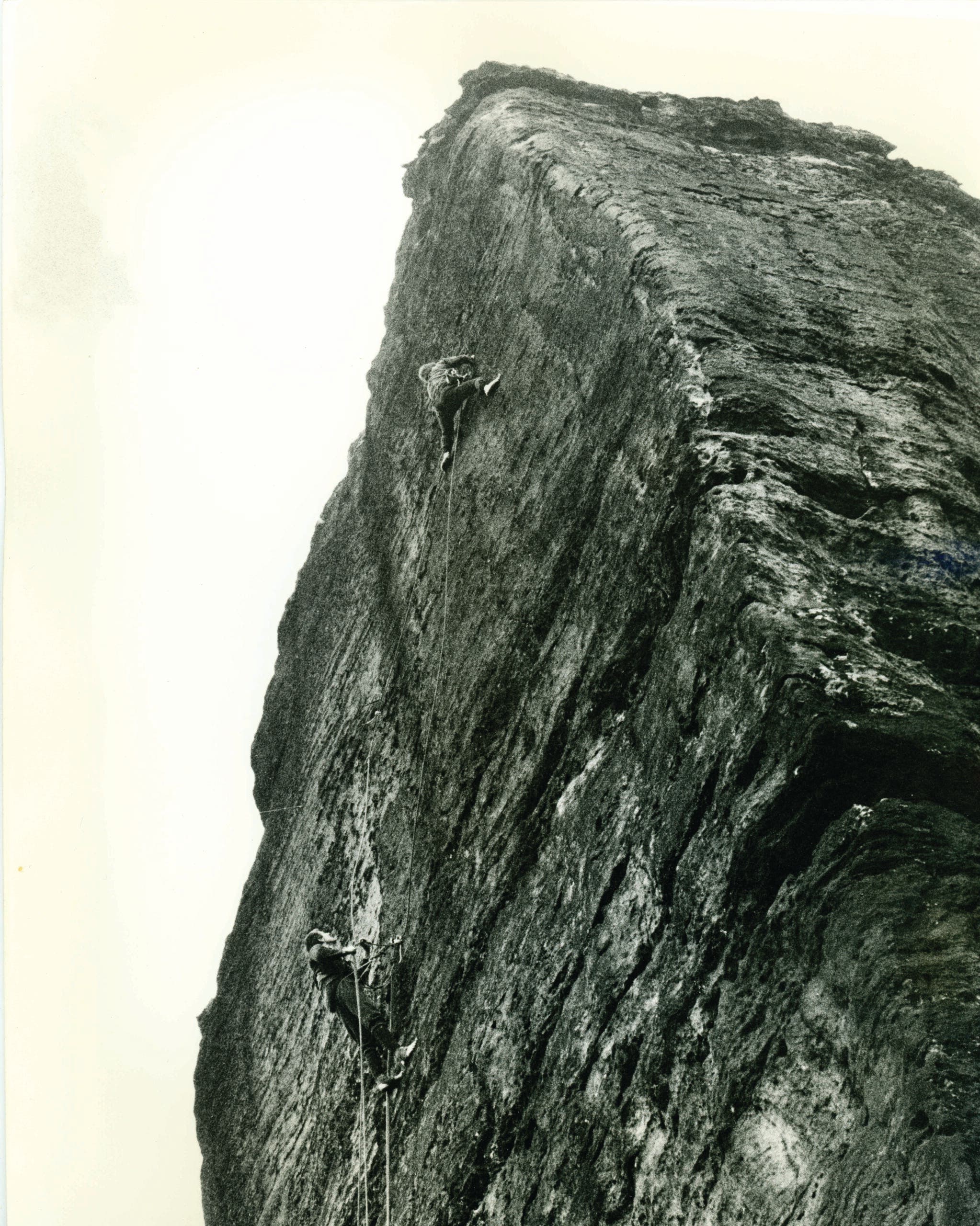

I had been worried about the lack of protection ever since I had seen Fritz’s movie. I can’t say my fears were exactly groundless, but most of the climbs I did were reasonably safe; even the hard ones I was shown looked no worse than some of the renowned modern climbs in Yosemite. A death route is, after all, a death route. In Dresden pitons are absolutely verboten, and nuts are unknown. Thus, the only form of protection (outside of infrequent horns and holes) is the bolt. They really go in for the large, safe variety over there, I’ll say that for them. Over half an inch in diameter and placed about five inches into the rock, they have huge rings into which a carabiner will barely fit. These bolts, called Ringen in German, rings by me, are rarely used for protection. I must explain this anomaly. Dresden climbing often consists of short but desperate class 4 pitches. Class 4 as in 5.7 through 5.11. (Ortenburger will smile ironically if he reads this.) Each ring is a belay station, often a hanging station, for the rings are installed not so much near ledges as just before hard moves. Therefore, it can be seen that the hard moves are reasonably well protected. Sometimes the pitches are less than 30 feet in length, and rarely are they more than 50 feet.

I recall once approaching a ring, relaxing as it got closer. I became horrified to find that I couldn’t let go to clip in. I really couldn’t let go. Briefly I thought of continuing, but the moves above definitely appeared to justify the ring. Finally I balanced and leaned and cavorted about and lunged for the mother. As I sat in my belay seat, it came to me that it would have been impossible for anyone to have placed the thing while leading. Fritz was watching from a nearby parapet, so I asked him about this seeming paradox. In fact, I opened my mouth too quickly, as usual, and stated in unequivocal terms that it was pretty low class to place bolts on rappel. “No, no, no!” he shouted instantly. “We don’t do that, it was placed on the lead.” But, Fritz, I couldn’t let go to clip in. No one could let go with both hands, for Christ’s sake, it’s vertical. The shouting match didn’t resolve itself at the time, but later in the beer parlor it turned out that these amazing chaps really had put them in on the lead, drilling the holes by hand—no hammers were used. The rock is fairly soft, and a strong person can cling onto pinch holds while the drill is turned with the other hand. Upon getting tired, the driller will climb down to a resting stance.

Sometimes the work is so strenuous that he must come back day after day to work on his hole. When the drill gets far enough into the rock, he will rest in a seat sling from the drill itself. But after such a rest, which one gathers is not terribly long for these Übermenschen, it’s off the seat, back to pinch holds and more grinding away.

Belaying is another strange story. Pictures of Europeans belaying have always amused me, and once in the Dolomites I saw a man belaying his entire family up a class 4 pitch; he wasn’t anchored, he had the rope over his shoulder, he was leaning over the void to give advice, and I fled lest I see blood splashed on limestone. I had, just the day before, watched a blind climber, and I was beginning to think that European climbing was really quite bizarre. Anyway, back to Dresden belaying. Because most of the falls are steep drops with no intervening protection, the locals have developed their own peculiar belay habits. It is difficult to recall the actual technique, let alone describe it here, but somehow the rope is placed around the waist, then twisted a few times to induce friction. It is devilishly hard to learn how to pay out rope quickly, and I was all thumbs at first. Although I was trying to adhere to the old “when in Rome, etc.” philosophy, I was a bit put off when I couldn’t use my own belaying style. I knew that I would never try to force a foreigner to adopt my own belay habits, feeling that however odd his system might be, it was at least safer to let him have the obvious advantage of familiarity. Sometimes, when Herbert couldn’t see me, I reverted to my California belay.

So far I have not mentioned the history of the area, primarily because I am intimidated by J. M. Thorington’s excellent article in the 1964 American Alpine Journal. Briefly, though, it seems that by 1914 the hardest rock climbs in the world were to be found in this area. Curiously, an American, Oliver Perry-Smith, was probably the best climber during the Golden Age of Dresden climbing, 1900–1914. I did only a few of Perry-Smith’s routes—a bold 5.7 jam crack flashes into my mind, but this was by no means his hardest route. My feeling is that there could easily be a 5.9 route somewhere among his 32 first ascents. The other great figure of these early days was Rudolf Fehrmann. He was not only a superb climber, but a visionary as well. He realized that by using artificial aids any tower could be overcome, so by means of lectures and articles he soon established the basic ground rule of Dresden climbing, which has persisted to this day: no aid climbing whatsoever. Another stringent rule was developed in those early days, and that is that only the first-ascent party can place rings; subsequent ascents do it the original way or come back. Or fall. As Thorington comments, “The death rate has always been high, mainly due to rope breakage and because the climber was not equal to the task.”

Accidents are a regular occurrence; ropes don’t snap much anymore, but arms do give out on strenuous sections and competition for the coveted Master Rating takes its toll. One day while walking along a dirt road we noticed a commotion: first-aid people gesturing effusively, revealing that orgiastic look common to ambulance drivers and rescue freaks the world over—blood, excitement, heroics. A youth had just smashed his spine on a climb we had done the preceding day. It was an unprotected 5.7 overhang with the chance of a 30-foot drop onto a wide, hard ledge. I had been truly gripped on the thing; it hadn’t looked bad, but my arms started to go at the crux move. With no finesse I adrenalined my way through, cursing Fritz, East Germany and climbing. And the next day we had done a wonderful climb, and on top Fritz casually mentioned that his cousin had taken a 150-foot groundfall here in the early 1920s. It seems the chap lost his balance on top of the slender pinnacle. You can bet I cowered low on that summit.

But I never got hurt; in fact I never even fell while leading. It seems that a lot of my fears are only in my head, as Dylan so sardonically puts it. Except for a few nightmarish armbusters that I had to do with Herbert (because they were such fine classics, I suppose), I actually enjoyed the climbing, just like I’ve heard can be done. It’s entirely possible that I got into the best shape of my life. And as the trip came to a close, I almost wished it wouldn’t. There was so much left to do. I figure I did only about 30 routes, and out of a total of 5,000 there must be about 1,000 that are really worth doing. So: 970 left, 30 per trip; Jesus, I might make it to the year 2014 yet.

This feature article was published in the 2017 50th anniversary edition of Ascent.