When Death Doesn't Make Sense

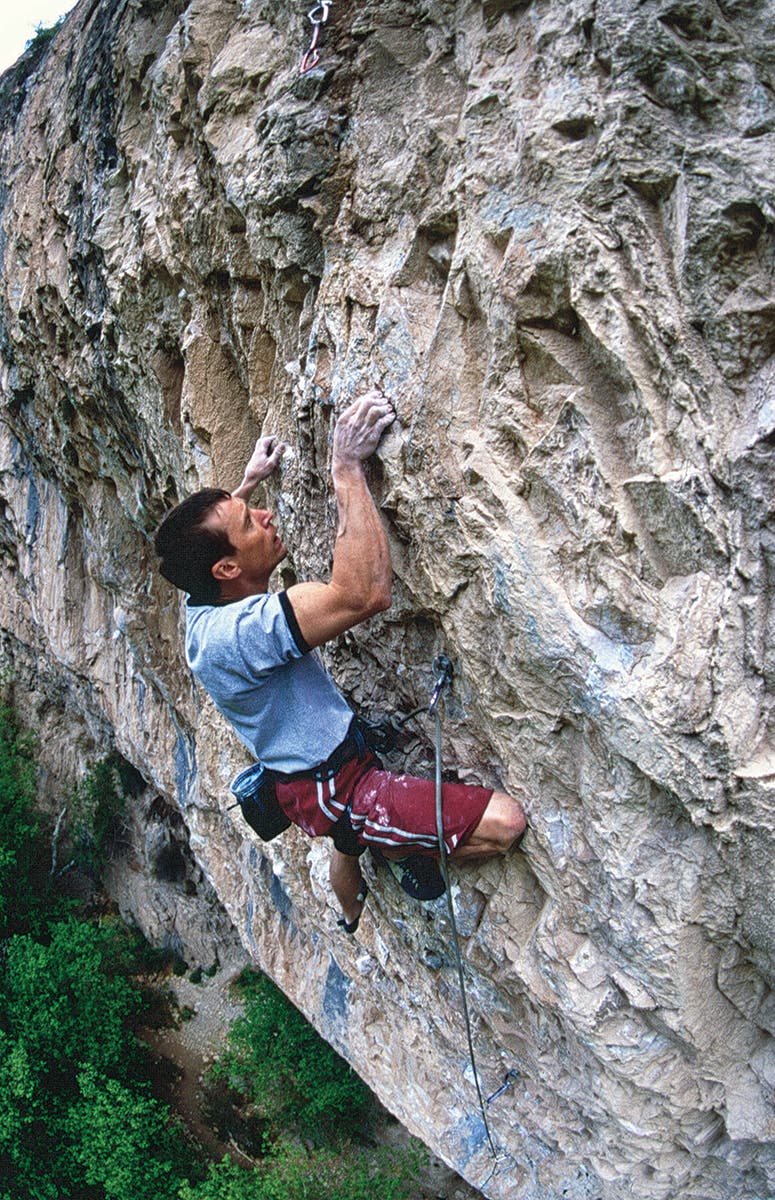

The Verdon Gorge, France. (Photo: Gérard SIOEN/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images))

This story first appeared in Rock and Ice, January 2015. It is published here for free, as a tribute to our friend and former co-worker Dave Pegg. Warning: This story discusses mental health and suicide.

I saw a ghost in the Verdon Gorge last spring. Maybe it was all in my head. Maybe that is the nature of all ghosts. But I saw it—a translucent apparition of a man. Tall. Thin. Ragged climber clothing. He just appeared on the ledge, 10 feet in front of me, facing out. Then he took one deliberate step toward the cliff and flung himself off the edge. Just like that. No hesitation. And the ghost was gone.

This ghost, I believe, belonged to a man who had actually jumped several years earlier from this very point: a small ledge just beneath the second belvedere. We knew this because there was a memorial—a bouquet of plastic, UV-faded flowers, sitting in a tiny alcove just above our rappel station.

The rap station accessed a beautiful collection of steep pitches on that classic blue-gray Verdon limestone. If there is such a thing as a good spot to jump, this was it—900 feet of free fall in a straight shot down to the Verdon River, twisting below us like an iridescent snake.

I asked my friend and climbing partner Alan Carne, knowledgeable über-local, about the flowers as we flaked our ropes. He told me a story about a local climber whose wife had cheated on him, who spiraled into depression and eventually jumped from where we currently stood.

The look on my face must’ve been unsatisfied—as if that was not a strong enough reason to commit what Albert Camus dubbed “the only serious philosophical question.” Suicide.

“This Gorge has moods,” Alan said. “And I think it really affects the people who live in La Palud. It can be so beautiful here. It can be so happy—like, joyful. But the entire mood of the Gorge changes in the winter. It’s hard to explain. This dark, ominous feeling settles in. … Winter is long. It affects people. It’s one of the main reasons I chose to live in Moustiers, not La Palud.”

Alan tossed a coiled strand over the edge. Gravity pulled the remainder of the rope, and the knot abruptly came taut against the anchor. “We’re such fragile creatures,” Alan said. “The line between life and death is so much more delicate than we think.”

Recently I’d been having thoughts that coincidentally (?) paralleled this very conversation—thoughts that maybe I’ve always had anytime I walk near a cliff’s edge.

I’ve pictured myself accidentally falling or rapping off the rope ends, and I’ve wondered if I’d turn to go headfirst or just look up at the sky.

The Verdon, a canyon where most of the climbing is accessed via rappel, is a place where you end up spending quite a bit of time teetering on the edge. Naturally, you find yourself contemplating this stark precipice and all that it represents.

I’ve probably spent thousands of days on the edge of one cliff or another. Not often, but sometimes, I experience a complex set of emotions in these situations. There’s the utter fear that I might accidentally fall, and the macabre curiosity of what that might be like. I’ve pictured myself accidentally falling or rapping off the rope ends, and I’ve wondered if I’d turn to go headfirst or just look up at the sky. Would I waste my final moments lamenting a stupid error that now couldn’t be changed, or would I enter a fully present, blissful state and enjoy the short, exciting ride while it lasted? Would I shout out something cool, like, “I’m the king of the world!” or just scream something dumb, like, “Fuck me!”

The other emotion I’ve experienced while standing on a cliff’s edge is a frightening if tantalizing realization that I possess the ultimate power: to take control of my anxiety-ridden position by throwing myself off and getting it all over with.

It would be as easy as a single deliberate step, and letting gravity do the rest.

This thought process isn’t suicidal, necessarily, because there’s no depression behind it. It’s more just a matter of exploring my own dark curiosity and I think these thoughts are common among climbers. An offshoot of vertigo, perhaps.

But maybe my cliffside fantasies speak more to the fact that I spend so much energy doing everything I can to avoid that big plunge. Climbing is the ultimate expression of freedom. But the price of enjoying this freedom is all the emotional energy we expend every time we enter the vertical realm and either directly or subconsciously try to overcome our fear of death. It’s probably more taxing than we realize. When stated this way, perhaps my thoughts are actually a healthy catharsis.

Still, I’ve always wondered what changes within a truly suicidal person—someone who turns these latent thoughts from being normal, healthy, cathartic daydreams into a final, unalterable reality. Is that transition really just as glib as the flip of a switch in your head? Are we that fragile?

Yes, the border between the binary states of life and death is as permeable as that single deliberate step forward.

Yet … nothing about that step makes any sense. It’s impossible to comprehend how that step ever becomes a reality.

Death is common in the climbing world, as it is in many adventure-sports communities. The longer you climb, the more dead people you know—it’s just a fact.

Yet for all the death that our community endures, I think that we climbers are just as bad at coping with it as everyone else. When climbers die, especially in sensational accidents such as a free-solo fall or on a faraway Himalayan peak, I’ve noticed that those deceased climbers take on a certain celebrity.

Because death is such a major part of the climbing world, when some well-known climber dies, many of us see opportunities to feel closer to death—and therefore, closer to climbing. For what reason would we ever feel compelled to put on such morose theatrics other than to affirm our identities as climbers?

The other uncomfortable reaction I’ve noticed to the big public spectacle that is a death in the community is a tendency to fall back on clichés like, “He died doing what he loved,” and guilt-ridden lamentations like, “It’s so sad that it takes a death to remind us how important life really is.”

Last November, my friend Dave Pegg died. Not from a collapsing serac or cutting-edge free solo. He killed himself in his apartment in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, an hour before he was supposed to meet two other friends for a day of cragging at one of the many local walls that he had singlehandedly developed.

Dave had a chiseled physique with hulking muscles and not an ounce of body fat. Up top, he looked like an Adonis, even well into his 40s. Down at the knees, however, it was quite a different story.

There was no glory in his death—just a lot of sadness and questions for all the friends he left behind.

Dave Pegg, aka “Master P”—a nickname bestowed upon him by Joe Kinder—was a climber’s climber. The most important details about Dave are that he was always in good spirits, he always seemed happy to see you, he absolutely loved climbing and he lived simply, working only as much as he needed in order to give himself every opportunity to travel and climb.

Most know Dave as the owner of Wolverine Publishing, a company he started over a decade ago that raised the bar for climbing guidebooks around the world. Dave’s books, such as those for the Red River Gorge, Hueco Tanks and Rifle Mountain Park (a guide he also wrote), were printed on heavy stock paper with gorgeous photos, accurate (often funny) route descriptions and essays by locals about the history and culture of the regions. The margin for publishing these works of art was slim, but Dave believed that the local climbing communities deserved guidebooks that good.

Dave had a chiseled physique with hulking muscles and not an ounce of body fat. Up top, he looked like an Adonis, even well into his 40s. Down at the knees, however, it was quite a different story.

Dave had these large, bulbous knees that, out in his beloved Rifle Mountain Park, provided him ample real estate for finding purchase on all the various knee-bars in the canyon. His knees definitely helped Dave crawl up many really hard rock climbs—one of them being The Gayness (5.14a), a multi-year project he finally redpointed just last year.

The only problem was that his knees were often too big for the spaces they were being forced into. There’s nary a protruding corner of limestone, nor a fin of rock, nor a protuberant sloper in all of Rifle, that Dave’s legs haven’t accidentally scraped against.

“Dave, your legs are gross!” we’d tell him. Yet he seemed pleased with his legs, wrapped in rubber kneepads with Broncos-themed duct tape. He wore his perma-scabs like badges of honor. Which, given the amount of hard climbing that he did in Rifle, they really were.

Even in these moments, when we poked fun at Dave, he would smile and laugh at himself. In fact, Dave always seemed happy. He had this incredible gift of crinkling the syllables of your name with a faint giggle of laughter when he first saw you … It was as if your presence actually tickled him.

These hellos are the first thing I am going to miss about Dave.

Dave was also well-known as “the absent-minded climbing professor,” and most of this reputation revolved around his role as an owner of animals—namely, dogs.

Over the years, I realized that Dave wasn’t a bad dog owner, necessarily. He just really loved his dogs, and didn’t have it in him to reprimand them.

The first time I climbed with Dave, I brought out a brand-new 80-meter 9.2mm that glowed like a neon sign for free beer. Meanwhile, Dave had brought out a stick-crazed puppy named Bellatrix, after the Harry Potter books he was so fond of. This dog, however, was a smart bomb programmed to impact water and mud. That morning, as Dave blindly jabbered on about the beta of his latest project, I watched Bell standing on top of my rope drenching the entire cord in dirty, brown grime. Dave stood right next to Bell—and did nothing. I couldn’t believe it! I went from being angry, to dumbfounded, to just absolutely fascinated by this guy who had no awareness that his animal was currently breaking the ultimate rule of climbing etiquette.

Over the years, I realized that Dave wasn’t a bad dog owner, necessarily. He just really loved his dogs, and didn’t have it in him to reprimand them. He loved that they ran free and wild. And I think that deep down he strived to live like that, too.

One time in the VRG, Bell escaped from Dave’s dutiful “watch” and ran out onto I-15. A UPS truck going 85 miles per hour slammed on its brakes and just barely came to a stop, very nearly killing Bell. Bad enough, but what happened next nearly ended all life within a 250-mile radius.

While the UPS truck driver sat there, probably thankful he hadn’t just killed this smiling, soaking-wet animal sitting on the freeway, wagging its tail and dropping a stick on the ground and looking up at the delivery man imploringly to please throw the stick, a military-grade flat-bed semi truck carrying a nuclear warhead rear-ended the UPS truck. The army vehicle fishtailed into the guardrail and nearly sent a nuke careening down into the Virgin River.

Dave, meanwhile, was up at the Blasphemy Wall, oblivious to the road carnage, and thinking about the beta on his project.

Dave was integral in getting route development re-opened in Rifle Mountain Park, after the town had enforced restrictions. I was always impressed with the consistent equanimity he brought to our meetings in his role as the head of the Rifle Climbers’ Coalition. He was like the fifth Supreme Court judge. He always had the greater good of Rifle climbing in mind, never took sides, and never let pettiness cloud his judgement. He had the vision to turn Rifle into the best climbing area in the world: a place with the least amount of attitude and the best community; a place with the safest fixed gear and the most interesting routes; and a place where 5.13d still holds respect!

Dave had a life that all of us envied. He came here from the U.K. in 1992 and carved out a slice of the American dream for himself. He built a successful business by raising the bar for climbing guidebooks. He gave people the tools they needed to have positive, life-changing experiences. And he did this all while enjoying the freedom to climb as much as he wanted, wherever he wanted.

In the wake of Dave’s death I’ve struggled to wrap my head around how someone who had so much, and who was loved by so many, could still lose sight of everything and take that step into the final unknown.

And that’s what’s so confusing.

In the wake of Dave’s death I’ve struggled to wrap my head around how someone who had so much, and who was loved by so many, could still lose sight of everything and take that step into the final unknown.

I saw Dave two weeks before he died. We spoke about the usual—climbing and bullshit. I knew he was going through a tough time, but a bright happy light still shone through all his words. He still seemed tickled when he spoke my name and said hello.

I was sitting in a restaurant, aprés climbing in Rifle, with my wife and two friends when we got the last bit of news that I was ever expecting to receive that day. Dave Pegg was dead.

Over the next 24 hours, my sadness at Dave’s death sank in. It humbled me, it grew deeper, and even turned to moments of anger. That old cliché about how it took Dave’s death to remind me to appreciate all that I have was true—and that’s what made me even more upset. I didn’t want Dave to be my cliché. And I resented those who I sensed were now drawn to Dave’s death—the way some fawn over celebrities—just to feel something, anything, about themselves.

I helped plan Dave’s memorial with a handful of other climbers in our community. We got together for dinners and jotted down details about what the memorial would look like. But quickly we put down our pens and found ourselves drinking beers and reliving all the great stories about Dave. These nights at the pub, planning Dave’s memorial, ended up being some of the most incredible and cathartic experiences I’ve ever had.

After the memorial, I felt a real sense of closure. I still don’t understand why Dave did what he did. But I have come to understand that there’s nothing necessarily wrong with using someone’s death for our own purposes, clichéd or not. I don’t feel guilty that it took Dave’s death to remind me to live more appreciatively, and to realize what an incredible network of friends I have in my own climbing community.

I just feel grateful for the gift that Dave’s death has been. I know that sounds weird to say, but it’s true.

Our mortality is both our greatest weakness and the universe’s most profound gift to us. It’s precisely this transience that makes life precious. We can’t always walk around in an enlightened state of embodying these virtues. But we can try harder to return to them, every day.

This article is free. Sign up with an Outside+ membership and you get unlimited access to thousands of stories and articles by world-class authors on climbing.com and rockandice.com, plus you’ll enjoy a print subscription to Climbing and receive our annual coffee-table edition of Ascent. Outside+ members also receive other valuable benefits including a Gaia GPS Premium membership. Please join the Climbing team today.