Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

As you move ever higher above your last piece and further outside your comfort zone, you grip the rock for dear life, even though you know the route is well within your ability. Yet here you are, only halfway up and too pumped to continue—everything feels way harder than it should. Most climbers have experienced this unfortunate situation: When you get scared, you hold on too tight and waste precious energy. The perceived solution: Focus on relaxing your hands to stop over-gripping the rock, thus lasting longer. While this does seem to make logical sense, over-gripping is actually not a significant factor in this perceived fatigue. Studies in applied physiology, neuroscience, and sports medicine point to stress itself as the culprit for accelerated fatigue. Anxiety can trigger the release of a certain hormone that can make you feel more pumped and tired than you actually are. Here we’ve provided some tips and tricks to conquer your fears and prevent the dreaded pump.

Physiology of Anxiety

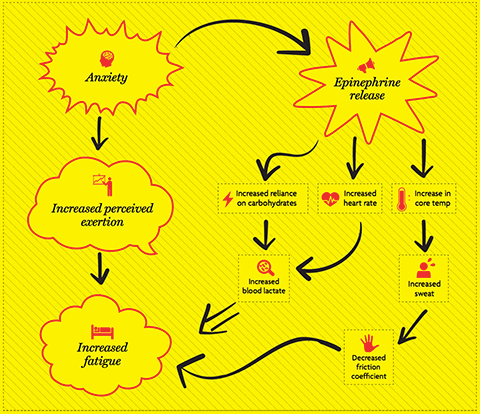

When we attribute poor performance to over-gripping, the situation is usually the same: We’re uncomfortable and experiencing a stress response. When we get stressed, whether out of fear, competition, anxiety, or any other worry-inducing factor, we experience a few common physiological changes. Our heart rate increases along with breathing. We switch energy systems from the slow-burning aerobic system, which runs primarily off stored fat, to the faster anaerobic system, which runs primarily off carbohydrates. Our core body temperature starts to rise, and we start to sweat more (another con in climbing). All these changes are mediated through one primary hormone: epinephrine (also called adrenaline), which is necessary when intensity suddenly increases, like powering through a crux.

If the only type of stress we experienced was the stress of exertion on the wall, and the only time we experienced it was during strenuous moves, then epinephrine would only ever be positive. The problem is that fear and anxiety cause stress before we even leave the ground, and therefore cause changes that are less positive/adaptive and more damaging to our performance. A study published in the Journal of Exercise Physiology in 2000 corroborates this: Novice climbers had significantly higher heart rates not only during a climb, but before it even began. The most likely reason for this is anxiety. An increase in mental stress causes an increase in epinephrine release, which then increases heart rate. The novice climbers began the climb with a body already in stress mode—the same physiological state more advanced climbers might only experience during a crux. This means that instead of moving smoothly through the easy sections and reserving stamina for the tough ones, precious energy gets wasted due to an unnecessary increase in epinephrine, caused solely by anxiety.

Feel the Pump

The premature release of epinephrine affects performance because the shift to relying on carbohydrates for fuel causes an increase in blood lactate and free hydrogen ions that cause muscular acidosis and the resulting pain. In other words, this increase in intramuscular acid levels causes the burning feeling in your forearms that is associated with pumping out. This increase in pain dampers your endurance and can reduce your resolve to continue, making you feel very pumped and fatigued when in reality, you likely aren’t. A 2007 study in the European Journal of Applied Physiology revealed that elite climbers derived 8.5% of their energy from carbohydrates on easy routes. As routes grew in difficulty, this number peaked at roughly 14%. On the other hand, for less-experienced climbers on easy routes, carbohydrate reliance began at 16.5%, almost double the rate for elite climbers.

Read: Why Climbers Should Lift Weights

Perceived Exertion

Anxiety can also explain why we think we are gripping harder, or working harder in general, even if the actual amount of work is not greater. Beyond the physiological changes epinephrine causes, anxiety correlates to perceived exertion, meaning the more anxious you are, the harder everything feels. Perceived exertion isn’t just a mental construct; it’s how our brain and body communicate during exercise to determine how fatigued we are. Anxiety throws a wrench in the works by increasing perceived exertion, essentially sending the body the wrong signal about how much work is being done and subjecting us to premature fatigue. A second factor that ups perceived exertion is core temperature, which is increased by epinephrine. Actual strength is unaffected, but this increase signals the body to slow down and allow core temperature to decrease. Anxiety, not over-gripping, is the real performance killer here. If we focus primarily on fixing our anxiety, then we fix all the negative elements associated with it. We shift our metabolism back toward burning fat, we cool down our core temperature, and we experience the climb on par with the actual difficulty and our abilities.

Fight Anxiety

- Figure out what your source of anxiety is, because you can’t change what you don’t understand. Are you nervous because you’re afraid to take a fall, because you know people are watching, or because the climb is above your usual grade? Once you know the source of your anxiety, create focused strategies (practice falling on the route, visit the crag when it’s less busy, etc.).

- Give yourself permission to fail. Onsighting problems is great, but the more pressure you put on yourself to perform, the greater your anxiety response will be. When you give yourself permission to fail, you remove your self-imposed consequences, and you’ll actually be more likely to succeed.

- Learn the climb by heart. In addition to saving energy by increasing your climbing efficiency, you also remove the stress that goes along with new situations. The better you know a route, the less you’ll worry about what you might encounter, how far the runout is between bolts, and where you might fall. According to one 2007 applied physiology study, simply repeating a route once decreased anxiety by 16%. Repeating it numerous times will only reduce anxiety further.

- Create a pre-climb or pre-comp ritual. We might laugh at the superstitious behaviors of many pro athletes (and their fans) before a game, but these behaviors have an adaptive advantage—they reduce anxiety. Rituals also help you define meaningful “beginnings” for actions (as in, “After I chalk up three times and clap twice, I begin to climb.”), which can help trigger your full concentration on the upcoming task of actually climbing.

Remember that stress is an adaptive response. The reason we experience physiological changes when we’re anxious is because they are intended to increase strength, power, focus, and drive, giving us the energy we need to succeed. If you’re anxious before a climb, focus on how these positive aspects of the stress response will help you climb, not how the debilitating aspects will hold you back, which can reduce your anxiety about, well, anxiety.

As a certified sports nutritionist (MS, CISSN), Brian Rigby works with climbers and other athletes at Boulder’s Elite Sports Nutrition in Colorado and writes at Climbing Nutrition.

This article originally appeared in Climbing in 2015.