Weak Grip? You Might Be Low On Electrolytes.

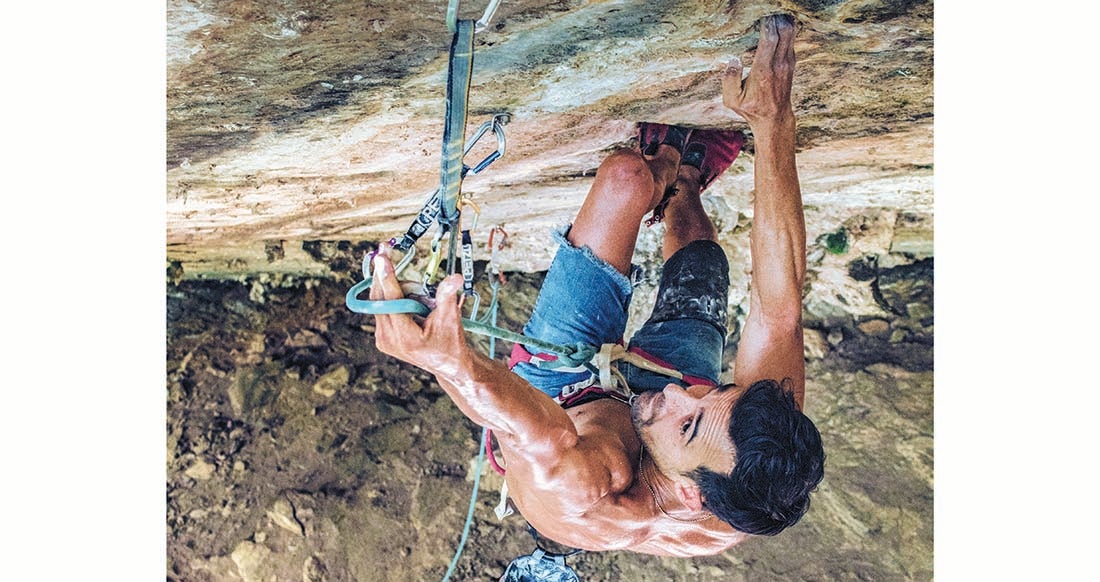

When we shed electrolytes on a sweaty day—as Darién Peteiro Veliz does here on a 5.13b at Viñales, Cuba—our performance can suffer. (Photo: JORGE LUIS PIMENTEL)

Recently, while I was out on a trail-work project in Tuolumne Meadows, a member of our group became agitated, complaining of nausea and an “almost-blinding headache.” She said she’d been drinking water, but even after resting in the shade and drinking 16 ounces of water, she still felt terrible. Then it dawned on me that she was probably deficient in electrolytes, the six minerals—chloride, magnesium, phosphorous, calcium, potassium, and sodium—that are essential for a functioning body. Fortunately, I carry Himalayan sea salt with me when I’m active. I had the woman place one piece under her tongue, and then eat some grapes. About 10 minutes, later she was up again, smiling, sans headache and stomachache, her electrolytes having been quickly rebalanced.

Water is the essence of our cells—every cell in our body not only contains water but is suspended in it.

Electrolytes are critical for our survival: They play a major role in energy transfer, metabolic processes, maintaining homeostasis, regulating muscle contractions, controlling nervous-system function, and balancing the body’s pH. You typically get them from food, especially nutrient-dense and whole foods. When dissolved in our bodily fluids, electrolytes become either positively or negatively charged, allowing them to move electrical signals throughout the body to assist with the operation of our brain, nerves, and muscles, as well as the creation of new tissue.

Hydration plays a major role here. Water is the essence of our cells—every cell in our body not only contains water but is suspended in it. The electrolytes help to regulate the amount of fluids in the body, as well as the fluids’ movement into and out of the cells. However, different cells use more water than others (fat cells contain around 20 percent water, muscle cells 75 percent, and blood cells around 83 percent), which naturally creates imbalances. The body thus balances water levels via osmosis, with electrolytes informing this process: Proper hydration relies on us having the correct electrolyte levels, while electrolyte function simultaneously depends on us being hydrated. As we saw in the example above, it’s a delicate balance, one we climbers need to pay particular attention to.

Electrolyte Drinks

If you use powders or tablets, look for ones that don’t have a load of added sugar but do have some glucose, as glucose helps carry water to the blood and also contains the electrolyte complex of calcium, potassium, and sodium. Good options include ATAQ Fuel Electrolyte Mix, Gnarly Hydrate, and Nuun Sport Tablets, as well as this recipe below.

Lemon-Limeade

(makes 16 ounces)

¼ tsp sea salt

¼ cup lemon juice

¼ cup lime juice

1 Tbs raw honey or real maple syrup

2 cups water

Combine all ingredients in a 16-ounce water bottle or pitcher, adding mint if desired. Can also be warmed in the cooler months. This drink contains all six electrolytes, though levels will vary based on the syrup and salt used.

Finding Homeostasis

Dehydration—having too little water in your body, thus throwing off electrolyte levels—can cause a decline in athletic performance and brain function. Common symptoms I’ve seen out climbing include: temperature-regulation issues (getting too hot or too cold), dizziness due to low blood pressure, irritability, swollen hands, muscle and extremity cramping (a “dehydration flash pump”), cottonmouth, and a weak grip. A classic telltale sign is dark, sticky, smelly urine—ideally, our urine will have a tint of yellow.

There’s also hyponatremia: too much fluid in the body relative to your sodium. This can look a lot like dehydration, with symptoms ranging from headache, confusion, drowsiness, fatigue, irritability, muscle weakness, muscle spasms, and cramps, to serious symptoms like seizures, coma, and even death. Within your first hour of exercise, water alone is enough to rehydrate you. But after those 60 minutes, you’ve depleted some of your electrolytes, and it’s prudent to start replacing them with food or a sports drink.

Even though we get electrolytes from foods, there can be deficiencies or imbalances due to factors like poor diet, poor health of the soil plants are grown in, hormonal imbalances, alcohol consumption, medications, digestive disorders, physical activity, heat, altitude, and how often we eliminate (pee and poo). Diarrhea and vomiting—think of how poorly you felt the last time you had food poisoning—can also impact electrolyte levels.

In addition to eating nutrient-dense and whole foods, climbers can benefit from electrolyte powders/tablets or natural electrolyte boosters like sea salt, coconut water, green juices, and smoothies, as well as homemade electrolyte drinks (see sidebar, facing page). If you use powders or tablets, look for ones with minimal added sugar but that do have some glucose, which helps carry water to the blood in a timely manner. A good powder or tablet will also have calcium, potassium, sodium, chloride, and magnesium.

The Six Essential Minerals

Chloride

What it does: Aids digestion (comprises hydrochloric acid in the stomach), balances the body’s pH, and helps maintain electrolyte balances. Along with potassium and sodium, chloride conducts electrical impulses throughout the nervous system.

How we lose it: Sweating, diarrhea, and vomiting. A deficiency can lead to low fluid volume, potassium loss, and pH-balance issues.

Good sources: Tomatoes, greens, olives, celery, seaweeds, rye.

Magnesium

What it does: Found in our bones, brain, muscles, and cells and blood, magnesium is needed for making protein, nerve transmission, immune health, and muscle contractions; it’s also involved in hundreds of enzymatic reactions throughout the body, including digestion, metabolism, DNA replication, respiration, and muscle contractions.

How we lose it: Through sweat and, during times of stress, through our urine. When we’re low, we tighten up everywhere, getting headaches, palpitations, muscle weakness, tremors, cramps, constipation, irritability, fatigue, low appetite, insomnia, apathy, apprehension, confusion, and high blood pressure.

Good sources: Nuts, seeds, legumes, dark greens, dark chocolate, dry apricots, brown rice.

Phosphorus

What it does: Strengthens bones and teeth, helps tissue growth and repair, helps us utilize carbs and fats, regulates heartbeat, and is key for proper nerve conduction and certain enzymatic processes. A diet high in phosphorus (soft drinks, processed meat, junk food, etc.) can negatively affect calcium metabolism. To maintain a proper balance, the ratio should be close to 1:2 (phosphorus to calcium).

How we lose it: Deficiencies are rare, as this mineral is found in most foods, but heavy use of antacids, alcohol withdrawal, and malnourishment can contribute. Symptoms of low phosphorus include anxiety, bone pain, fatigue, irregular breathing, irritability, weakness, and weight changes.

Good sources: Asparagus, bran, brewer’s yeast, corn, dairy, eggs, fish, dry fruit, garlic, legumes, nuts, seeds, poultry, salmon, whole grains.

The following three minerals form a complex—they all play a role in nerve transmission and muscle contraction; a significant deficiency in any one can cause cramping. Eating foods rich in these minerals helps compensate for the loss of these electrolytes through sweating, as with a high-exertion day at the cliff.

Calcium

What it does: Calcium is the most abundant mineral in the body. It builds healthy bones and teeth, helps muscles contract and relax, and is important in nerve functioning, immune-system health, blood clotting, and blood-pressure regulation. To help you absorb calcium in the digestive tract, you need vitamin D, which is produced in the body through the action of sunlight on the skin. You might also take a vitamin D supplement or eat foods like dairy, dark, leafy greens, cod-liver oil, eggs, liver, and cold-water fish like salmon, mackerel, and herring.

How we lose it: The primary cause of calcium deficiency is a vitamin D deficiency. We also lose calcium through sweating, elimination, and the growth of skin, hair, and nails. Additionally, too much phosphorus will cause excess calcium excretion through our urine. If we do not have adequate calcium, the body “borrows” it from our bones, leading to symptoms like aching joints, rheumatoid arthritis, and tooth decay.

Good sources: Dairy, canned fish with bones, dark, leafy greens, asparagus, oats, legumes, figs, nuts, sea veggies.

Potassium

What it does: Potassium works closely with sodium, but is also regulated by magnesium in the cells. It’s needed for proper fluid balance, nerve transmission, muscle contraction, energy metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, and tissue growth (think muscle). Potassium also regulates the transfer of nutrients through cell membranes, and it’s essential for the conversion of blood sugar into glycogen (the stored form of blood sugar found in the muscles and liver).

How we lose it: Profuse sweating, alcohol consumption, diarrhea, vomiting, and long-term use of laxatives, aspirin, cortisone, and some diuretic therapies. A potassium deficiency results in lower levels of stored glycogen, causing the number-one symptom of fatigue, followed by muscle weakness, slow reflexes, skin problems, insomnia, irregular heartbeat, and anxiety disorders.

Good sources: Red meat, flounder, salmon, sardines, cod, dairy, parsley, spinach, lettuce, peas, lima beans, potatoes (especially the potato skin), citrus fruits, bananas, apples, avocados, raisins, apricots, whole grains, legumes.

Sodium

What it does: Sodium works closely with potassium, helping control fluids in the body and thus impacting blood pressure (e.g., a high-sodium diet with a low potassium intake tends to elevate blood pressure); it’s also necessary for muscle and nerve function. Those on the Standard American Diet (SAD) typically get much more sodium than needed, resulting in conditions like PMS, water retention, and high blood pressure.

How we lose it: Severe perspiration (the body can lose up to eight grams of sodium per day through sweat), exposure to hot weather, or adhering to a low-sodium diet. Low sodium levels can result in muscle cramps, heat stroke, blurred vision, edema, and low blood pressure.

Good sources: Most foods contain some amount of sodium—you can find high amounts of it in staples like seafood, sea vegetables, beef, and poultry, as well as in celery, beets, carrots, and artichokes. Salt tablets or ingesting small pieces of sea salt can also be beneficial.

With a little bit of planning for those hot, sweaty climbing days, you can treat yourself to healthy and electrolyte-friendly snacks like cucumber-and-tomato salads, whole avocados with carrots to scoop, chia pudding with yogurt and fresh berries or pear, or dried-fruit-and-nut mixes like mango and cashews, pecans and dates, or walnuts and apricots. Celery and nut butter, and fresh, seasonal fruit, are also super simple and highly effective at supplying electrolytes.

Katie Lambert is a pro climber in Bishop, California. In 2016, she received her master’s in nutrition, and has put it to work through her business High Sierra Nutritional Wellness.

The Keto Diet and Electrolyte Loss

People who follow a ketogenic diet—low-carb, high-fat—can be at a higher risk of losing electrolytes: Their kidneys excrete more sodium as a result of less insulin being released. Then, as the body starts to lose sodium, potassium and magnesium levels can become imbalanced. This is the “keto flu,” with symptoms like nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, headache, irritability, weakness, muscle cramps and soreness, dizziness, poor concentration, stomach pain, poor sleep, and sugar cravings. If you’re on a keto diet, either take a mineral complex or supplement via drinks and powders. Additionally, people who eat a diet centered on highly processed options like TV dinners, fast foods, and junk foods—or who are alcoholic—will be in similar need of supplementation.